The Humble Knitter’s Lament

My personal traditional craft practice and why reviving these skills is a act of dissent against digital distraction

By

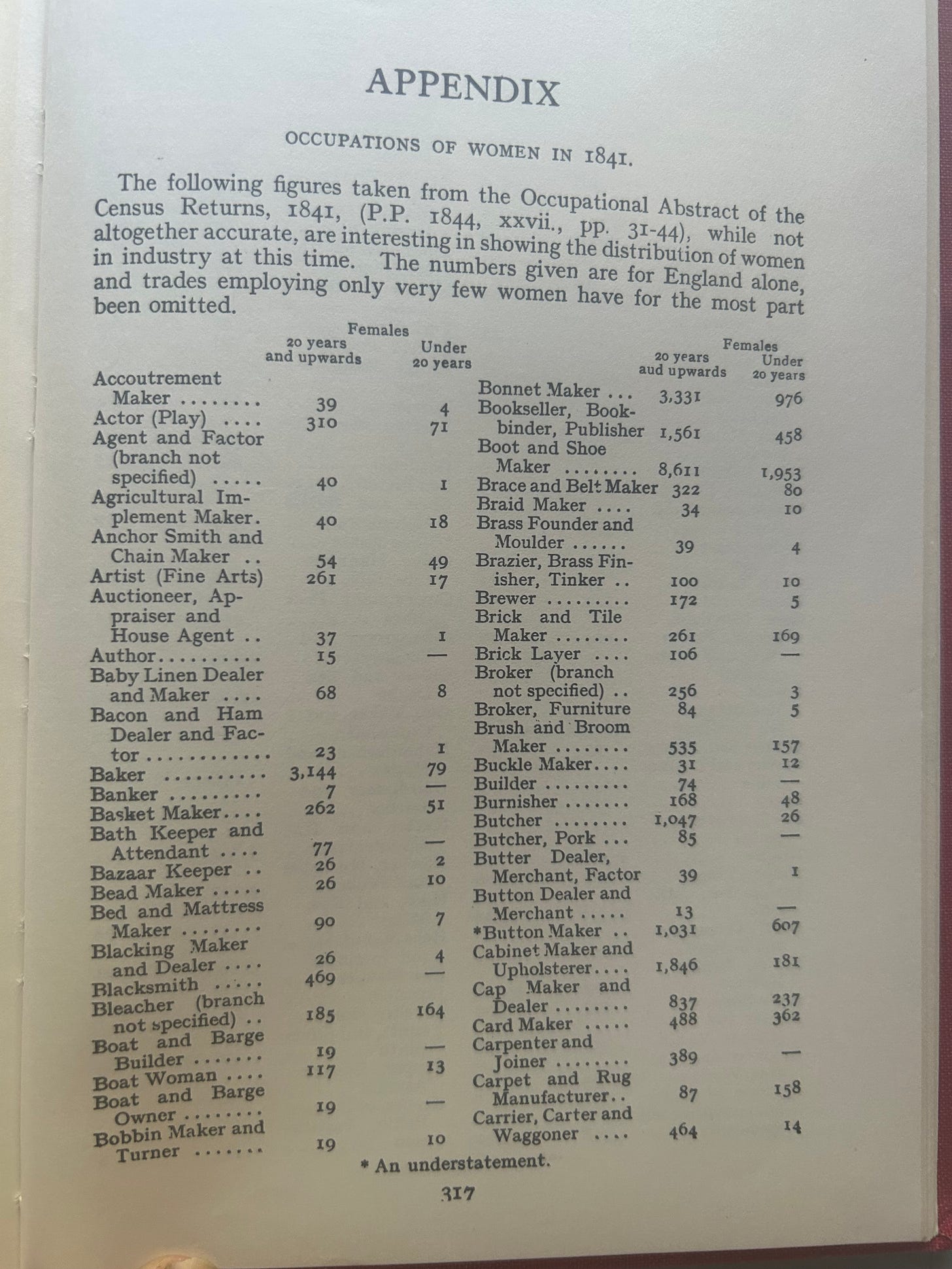

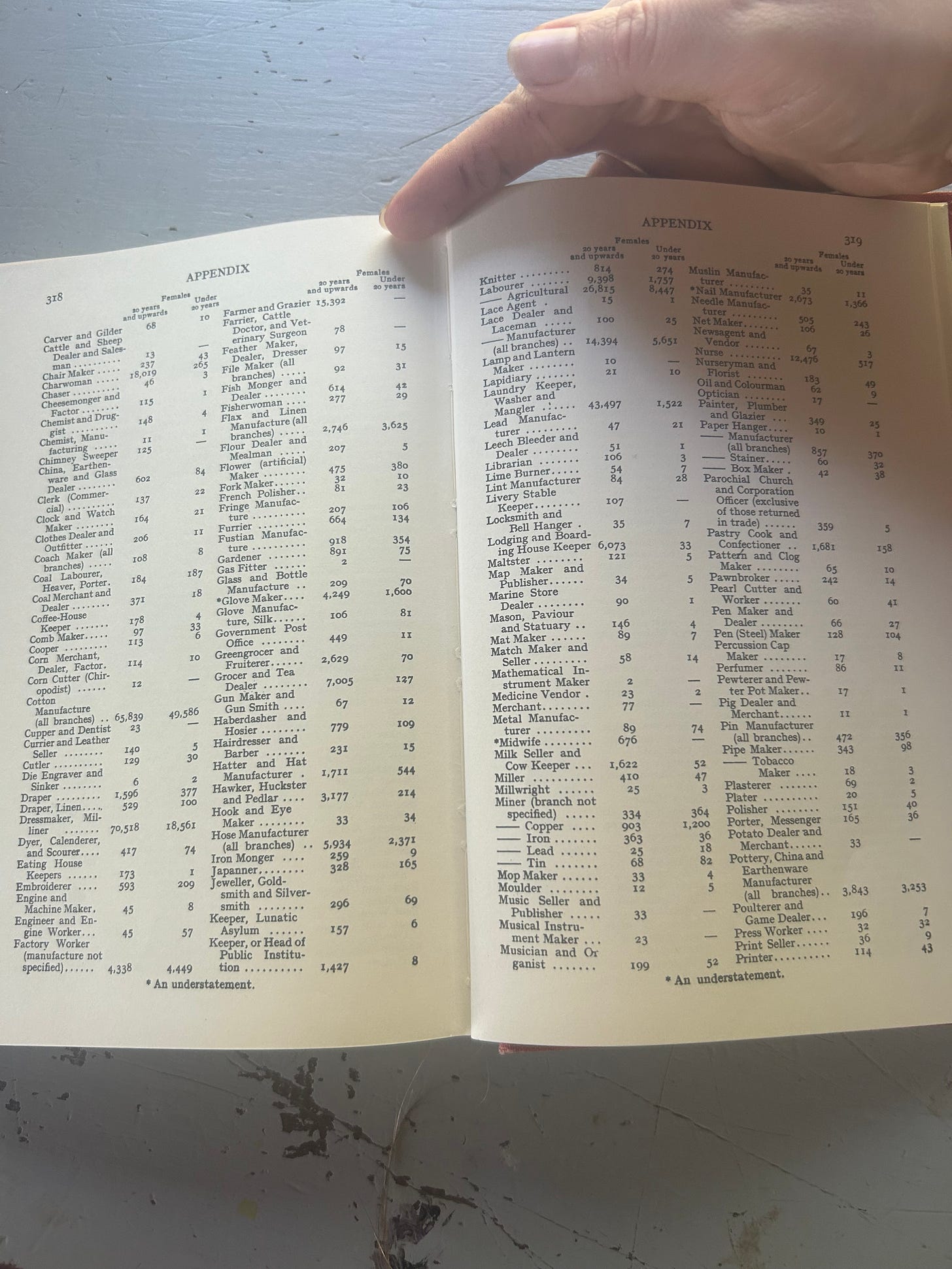

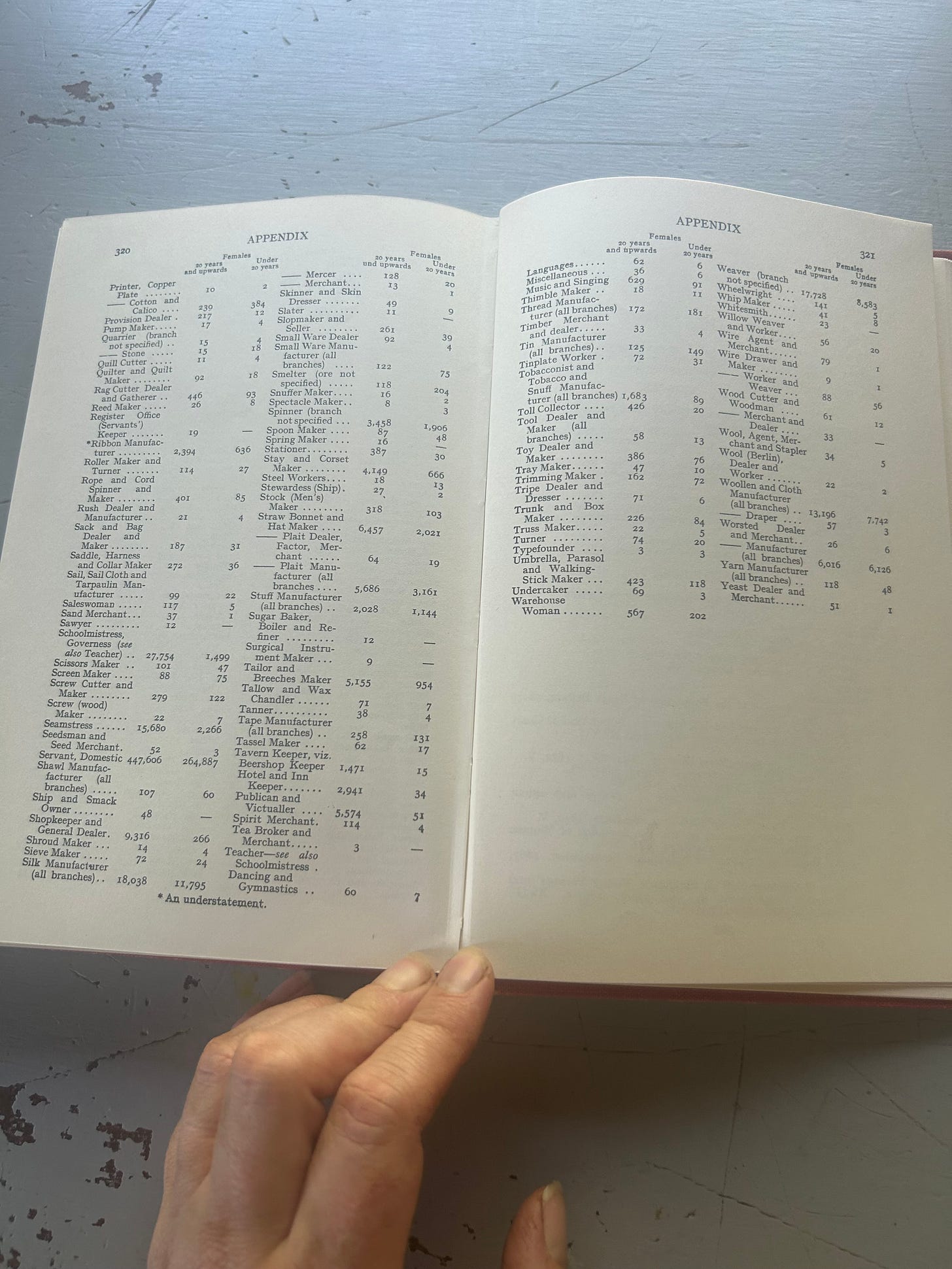

fromI have a voracious hunger for information about the women of the past and how their day-to-day lives looked, particularly the work they took up. I believe my need for this knowledge comes from a place of inner turmoil with the current state of things. A state that I have been citizen of begrudgingly, and which I believe has caused me some considerable measure of mental and emotional strife. A state which I choose to try my best to dissent from, and which I hope to build scaffolding against for my children to the degree it is possible. This is why my newsletter is called “Women’s Work”. Both because I am interested in the work of women past and present, and because to me, it is women’s work to design dissent. In my ongoing yearning for bits and pieces of the past, I picked up a copy of Ivy Pinchbeck’s book “Women Workers and the Industrial Revolution, 1750-1850”. In the appendix, which I will share photos of below, there is a long list of women’s occupations in England from 1841.

Pick your poison-what's your ideal 1841 women's work combination? Butter dealer/bonnet maker? Confectioner/leech bleeder? Tallow chandler/ seed merchant?

The patterns I notice are of no surprise. Women were dealing in care work, agricultural work, and craft work. Yes, there were a few locksmiths and tape manufacturers, but most women were weavers, dressmakers, domestic servants, charwomen (those employed to clean offices and houses), laundresses, nurses, school mistresses, and farmers.

Seeing that the top professions include such titles is again, not shocking. Care work has always been women's work-but today so much of what these professions entail is shared with technology and also gate kept via expensive and tedious certifications and degrees. I would know, being a nurse with upwards of $30,000 in student loans who learned her skills on mannequins in a fancy “skills lab”. I graduated nursing school never having ever placed an IV or drawn blood on a living, breathing human being. I much rather would have done an apprenticeship and been given the honor of slowly but surely acclimating to the intimate, hands-on work that nursing should be. While some amount of scholarship is of course prudent in these fields, I fear we have lost the unique human touch that is so vital to the core of their value as technology and increasing levels of education become “necessary” to engage in them professionally and therefore make a living wage from what has always been our domain as women.

The craftswomen-the dressmakers, weavers, lace and linen makers, knitters, straw milliners, stay and corset makers, and the basket weavers had jobs that required skills that today in the Western world are seen solely as luxury hobbies. We have come to value the sort of beauty these women imbued their respective crafts with less in favor of utilitarian design. We have come to accept a poor standard for quality over the past few generations who increasingly wore more and more poorly sewn clothes made from plastic derivatives and the like. We have also came to expect the manufacture of textiles and home decor to be outsourced to foreign countries. As all of these phenomena have evolved, these skills have become trivial.

Agricultural work is outsourced altogether. Either to machines, immigrants, or shipped in from faraway places. Many live in urban environments where growing a single tomato vine feels impossible. Children don’t know that peanuts are a plant, or that peaches don’t grow year round. We are divorced from the source of the very nourishment that sustains us, and in doing so, that sustenance has become increasingly manipulated and unhealthy.

“Mother” isn’t on the list, of course, perhaps because it was both an assumption that many women were mothers and also because it was not considered work. We all know mothering is often the most intimate, involved and ongoing women’s work a woman who is a mother engages in, and so in my own work of designing dissent, my status as “mama” is relevant.

Thinking on how much so many of us yearn to master the skills of yore, desire nourishing food produced with some semblance of tenderness, and are naturally inclined to lend our hands and hearts to the work of caring-for our own children and the children of others, for our friends, for the elderly, and for the sick, I cannot help but notice something about the state of things. Our kids are in day cares with strangers. Many of us don't know how to cook or grow a pepper. Most all of us have never mended a worn sock. Our inner knowings, manifested as desire, are ignored in favor of compliance with the demands of the market and the state, and our souls reap the consequences.

This is a problem. It’s a local versus global problem. It’s a generational skills deficit problem. It’s an economic problem. It’s also a tolerance problem. We tolerate too much. I cannot countenance a life removed from hands-on, hands-in living.

Enter knitting. This is but a small task and skill among several others I have been blessed to learn and use in my life thus far, but it is the one I find most worth writing about. It is the traditional skill I most enjoy. It is the skill I feel comfortable teaching others. It is a skill that ties me to other women. It is also the skill which I credit with aiding me in my sobriety from heroin, which I quit using 13 years ago.

I have attempted to unravel the reasoning for my addictions many times over the years and the conclusion I have come to is that I do not feel capable of being well-adjusted in a digitized society. I have felt this my whole life, but only recently put this into words for myself in hopes it may resonate with other people suffering addiction. I fully explain this in my essay Requiem for a Past Life.

Knitting, surprisingly enough, truly helped me work through the earliest days of sobriety. The movement of my hands was distracting enough to buy myself time from cravings. It truly became my “next right thing” in some moments of mental anguish. I had learned to knit as a teenager and I had done it enough that I had muscle memory for the basic stitches, and this was a comfort. I had something to do while I listened to music that felt both productive and meaningful, and this made me feel valuable—something I hadn’t felt in a long while. I wasn’t just sitting around wasting away letting my discomfort with the world rot me away into the ether anymore, I was making something, something beautiful and useful. I was doing something the women who lived before me would recognize and appreciate. I was making a blanket for the baby I was blessed with, and who was the motivation for my sobriety. That baby would have a mother who knit her Halloween costumes and britches to cover her cloth diapered bottom, not a strung out IV drug addict who couldn’t manage reality.

And yet, reality as it stands is still momentously unacceptable to me. The constant drive for progress that has no end point, the all-encompassing social-media-overlording of our lives, the culture that we live in that values sterility over vitality, the overwhelmingly distracting nature of the demands of daily life in this society—I do not consent to it, for myself or my family. And so, I knit. I knit, among other things, and I teach my children to knit, among other things.

In terms of all traditional skills that we deem worthy of ushering into the future, I think we just have to be the generation who has to teach ourselves so that we can teach the next. Before it is too late, before these things go extinct. The extinction of craft is a real threat to our quality of life. Consider how you feel when interacting with environments that are more handmade versus environments that are sterile in nature. The stark contrast in how these things impact your emotions and mental state should tell you all you need to know. We need beauty in a visceral way, and we need hands capable of creating beauty.

I choose to show my children the small, ordinary magic of a garment almost untouched by industrial-anything. The way a warm half-knit sweater feels sitting in your lap as you enjoy the quiet, tedious movement of fingers that know the way on a cold winter afternoon. The extreme sense of satisfaction one experiences from finishing a project, weaving in your ends, blocking it, waiting for it to dry—and then putting it on your body and seeing it fits and feels just right. This is the stuff of life!

I have been a knitter for nearly 20 years at this point. In this time I have learned patience, perseverance, attention to detail and the value of sitting quietly. I have come to know the tangible difference between yarn that is plastic in its origins and fibers that come from living things. Wool or cotton feels and knits up differently than acrylic, and requires much more care and attention. Natural fibers are unruly in some cases, they require hand washing, and God forbid you put them in a dryer. They are slowly made and slowly tended to. A slow sweater in a fast world warms me like no other.

And so, I will push on in my quest for a slower life more aligned with the needs of my physiological self and the similar needs of my children. And so, I will cast on again.

Cast on the stitches of hope that, once brought together, combine to make textile tokens of my love. Sitting at my humble old kitchen table or in front of the wood stove my husband built to warm us, I will carve out the time to just sit and let my hands do what they know how to do, showing my children that this is enough. I will plan projects with fervor, consciously spending the money I can on fibers made from nature, spun and dyed by people of similar mindset. I will choose to make what I covet if I can. I will gift some of these things, soft and intricate parcels of intention. I will choose to sit down daily and participate in this thing my ancestors may not perceive as foreign and strange, in full view of my children, who may one day do the same. This, in place of screen time or driving somewhere to distract myself and sometimes even without indulging in a playlist or a listen to a favorite podcast. Sometimes we must choose the quiet or the conversation, and in fact a skill like knitting is best paired with such.

I will cast on these stitches, and in doing so, I will cast away some measure of digital distraction, distraction from what is of true value.

If you would like to leave a comment, you can do so on the main post “A Library of Unconformed Lives” here:

or visit

’s original post here: