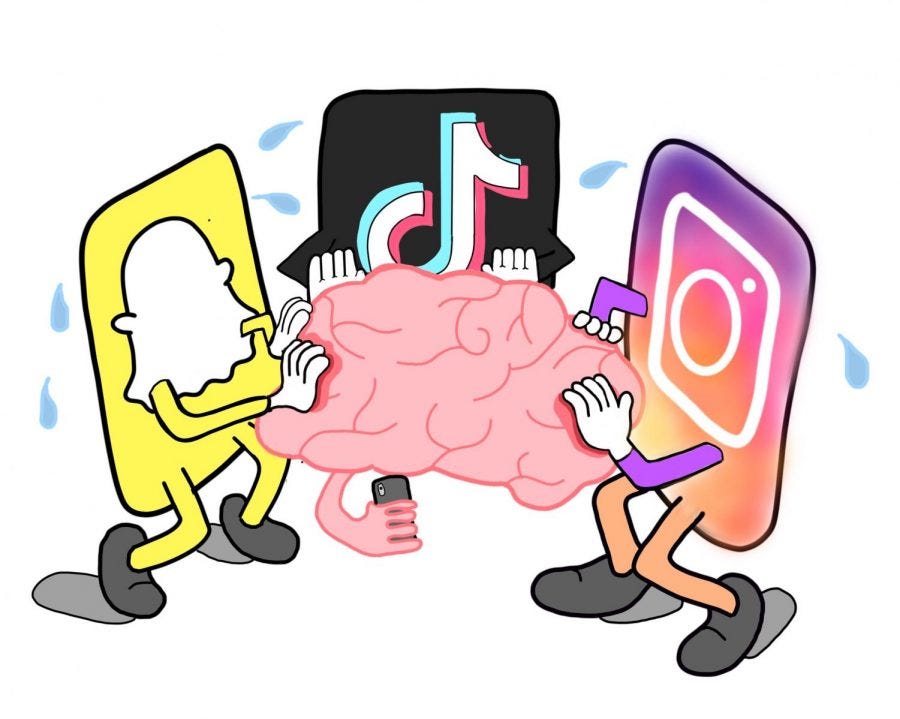

Our children’s brains are currently being sacrificed on the altar of TikTok in exchange for snippy videos on ‘How to peel a banana’ (over 250 million views) or ‘Lip syncing in front of a bathroom mirror'(over 600 million views). These seemingly benign, mildly amusing, mostly navel-gazing shorts have been dubbed ‘digital fentanyl’ and have prompted even mainstream media to take note with articles such as: Broken classrooms: Why teachers and parents don’t stand a chance, ‘TikTok Brain’ is killing students’ ability to learn, or TikTok Brain Explained: Why Some Kids Seem Hooked on Social Video Feeds just to name a few.

I regard the rise of ‘TikTok Brain’ as one of the most central issues in education today. Every single aspect of education is tied firmly to the ability to pay attention. Once the capacity to pay attention is lost, everything else in educational approaches or curricula will cease to matter. This is equally true for public, private, or homeschooled students.

What is TikTok brain?

Neuroscientists have shown that "TikTok Brain” is caused by “the dopamine rush of endless short videos”. This continuous rush of feel-good chemicals is feeding students on a diet of mental candy crack, while asking them to consume comparative broccoli in the classroom setting. Even without social media, the ever increasing amount of screen time has led to a decline in attention and concentration skills. Paul Bennett, the director of Halifax-based firm Schoolhouse Institute and adjunct professor of education at Saint Mary’s University, notes that, “students who perform a task just in sight of their phone (regardless of if they are using it) do about 20 percent worse as it still distracts them. In addition, students who are on their phones more in class get worse grades, regardless of gender or previous grade average.”

Incredibly there are educators who cheerily walk along with the “Electronic Pied Piper” (as one insightful commenter labelled TikTok). Among them Brock University education professor Shauna Pomerantz. She and her 14-year-old daughter Mimi were featured in a news segment, which according to Bennett, “left the distinct impression that TikTok was a gateway to ‘experiential learning’ and incessant consumption of social media was harmless.With guidance, it might even provide openings to discuss serious societal issues such as violence against women.” Pomerantz maintained that her daughter gathered information on important news from around the world via TikTok – Hmm, this reminds me of a ‘reliable’ TikTok news source that led one of my friend’s young relatives to proclaim to her high school class that according to TikTok “100% of women have been raped”. Bennett points out that, “These little videos can perpetuate mythology, incorrect information, slanted views and actually discourage critical thinking”.

TikTok’s short bursts of fleeting images are a direct antithesis to learning, which requires attention, careful thought, and concentration. What is particularly troubling is that these dopamine-packed videos eat away at attention across the board. In a recent Wall Street Journal article, Michael Manos, clinical director of the Center for Attention and Learning at Cleveland Clinic states that, “Directed attention is the ability to inhibit distractions and sustain attention and to shift attention appropriately…If kids’ brains become accustomed to constant changes, the brain finds it difficult to adapt to a non-digital activity where things don’t move quite as fast.”

What has caused the rise in attentional difficulties with students?

The pandemic has essentially gorilla-glued phones and teenagers into a permanent embrace. The amorous relationship was already well on its way before 2020 however. Research by Twenge and others found that teenagers’ media use roughly doubled between 2006 and 2016 across gender, race, and class, leaving books in the dust: By 2016, just 16 percent of 12th-grade students read a book or magazine on a daily basis. One can only imagine how these numbers skyrocketed during the pandemic period.

School closures, lack of recreational events, social distancing, and many other relationship-negative pandemic measures have left evident scars. When students returned to in-person classes, their social skills had declined significantly. Many were struggling with depression and were withdrawn. Many struggled to concentrate and follow directions. Many had lost their ability to persevere or even just to simply get along with each other.

Phones are easy but they destroy attention.

Relationships are hard but they are required for learning.

What effect does ‘TikTok brain’ have in the classroom?

A continuous noisy hum of disorder and distraction is not an ideal breeding ground for attention. Try long division with someone whispering next to you (I did this morning while helping my fifth grader with his math, and it was nearly impossible). Students have habituated themselves to switching tasks every few seconds. Indeed in 2017, before the new crop of social media apps, a study found that even undergraduates, who are more cerebrally mature than K–12 students and therefore have stronger impulse control, “switched to a new task on average every 19 seconds when they were online.” Learning to read, decode meaning, or master basic arithmetic, cannot be accomplished with such small increments of saltatory attention.

Bennett explains that, “the more time young people spend in constant half-attentive task switching, the harder it becomes for them to maintain the capacity for sustained periods of intense concentration. A brain habituated to being bombarded by constant stimuli rewires accordingly, losing impulse control. The mere presence of our phones socializes us to fracture our own attention. After a time, the distractedness is within us.”

Through their steady social media drip, students have been practising half-attention. And they excel at it. When a learning task requires them to slow down, reflect, or analyze, their mind swiftly turns the corner and gropes for something more interesting and entertaining to latch onto.

I recall when, starting in the late 90’s, schools eagerly embraced anything ‘tech’. In 2001, writer for Edutopia, Suzie Boss, gushed, “Social media opens new possibilities for connecting learners and taking education in new directions.” Two decades later, schools now battle the sweeping effects of ‘Tech Immersion’. Near constant distraction by phones and other tech has serious side-effects especially for reading.

Some might argue that students are merely ‘multi-tasking’, which after all is a useful skill, right? Not so, according to new evidence-based research which has disrobed multi-tasking as a myth. Ubiquitous use of cellphones is linked to distractability (in the workplace and schools alike) and leads to more “frequent errors, higher levels of stress, reduced cognitive ability, and lower productivity.”

Learning on TikTok Brain can be summed up as haphazard, half-attentive, and thus ultimately hopeless.

Next week:

TikTok Brain Cure with Three Ingredients

References:

Jargon, Julie. (2022). TikTok Brain Explained: Why Some Kids Seem Hooked on Social Video Feeds. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved on January 10, 2023, from https://www.wsj.com/articles/tiktok-brain-explained-why-some-kids-seem-hooked-on-social-video-feeds-11648866192?mod=e2tw

Lemov, D. (2022). Take Away Their Cellphones … So we can rewire schools for belonging and achievement. Education Next, 22(4), 8-16.

Image Credit: Nyomi Fox