The Search for Stillness in a Mad, Mad World

Building mountains of silence amid the speed, clamor and distraction

In 1991, two hikers discovered a dead body while crossing a glacier in the Alps. The body turned out to be a man who lived over 5000 years ago. Researchers dubbed him Ötzi, but he’s also been called the Iceman, as his corpse had been encased in ice.

Analysis of the remains suggests that Ötzi died of several injuries, including an arrowhead embedded in his shoulder. He also had bad teeth, bad knees, lactose intolerance, and probably Lyme disease and a stomach infection.

He had a genetic predisposition to atherosclerosis too, meaning if he hadn’t been murdered in his mid-40s, he would have eventually died from a heart attack or stroke—despite getting a lot of exercise and eating a healthier diet than many modern people.

If Ötzi had been born today, he might have gotten treatment for his medical issues and lived a lot longer. Civilization has brought us many ills, but it has its advantages.

One of the stranger findings, based on analysis of Ötzi’s fingernail, is that he suffered from three periods of intense stress during the last few months of his life.

But what does “stress” actually mean for a stone-age man? As one commentator has observed,

We do not know how he reacted to the diseases he may have been afflicted with. He may or may have not viewed them as a punishment by gods or spirits. He may have suffered from them, but he may also have accepted them as a burden he had to carry.

One of the disadvantages of civilization is that the same conveniences and technologies that help us live longer also create a greater separation between us and the natural world. Our experiences are more cerebral than sensory; more reflective and less spontaneous. Ötzi wandered the wilderness and hunted for food; we click on websites and drive on paved roads. We might not have any more stress or suffering than people in the past, but it’s possible we experience it differently, as disturbances in our emotions, our thoughts, our identities.

Ötzi was probably convinced he belonged to the gods, while we have no idea where we fit in the universe, or else dismiss the issue as irrelevant, as stone-age superstition, as having no place in serious modern discourse.

And yet, we know we’ve lost something in our separation from the natural world, and from God and the transcendent. We have dentists for bad teeth and surgeons for bad knees, and online worlds to satisfy our every desire, but the human spirit has never been more unsettled.

Is it possible to recover quiet, stillness and eternal meaning, here in the belly of the modern monster?

A pregnant nothing

An article in The Atlantic in 2022 begins with this story:

Andrew Formica, the 51-year-old CEO of a $68 billion investment firm, abruptly quit his job. He did not have another job waiting—or anything else, it seems. When pressed about his plans, he said, “I just want to go sit at the beach and do nothing.”

A lot of us would love to sit on the beach and do nothing, but not many of us are financial elites who can kick back as long as we want.

Even if we could, is “doing nothing” really a life?

No, probably not permanently, yet there’s a constructive sense of doing nothing. My ex-Zen-turned-Christian friend Ellis Potter might call it a “pregnant nothing”, which is not total emptiness, but possibility.

Regular experiences of doing nothing, seeking nothing, can help weaken the usual patterns and routines that keep us rigidly locked in a certain way of seeing things. We don’t have to be financial elites to do that, yet we do need to deal many barriers, not the least of which is the great engine of civilization, which runs at high speed.

In this great engine, we’re often hurriedly attending to our jobs, relationships, and responsibilities, but speed blurs perception. When I work with clients in therapy, one of the first signs they might struggle to change is an unwillingness or inability to make time each day to work on their difficulties. Their lives are just so busy it can be hard for them to stop long enough to see things in a different light.

Speed and overstimulation deform our perception of ourselves and the world, much as the ripples on a pond deform what might have otherwise been a mirrorlike reflection of the surrounding trees and sky.

In the engine of the modern monster, we see bits and pieces that flicker past on the ripples of the mirror. We see snippets and parts rather than wholes, and we function by grasping the bits we can see and get accustomed to a lopsided left-hemisphere perception of the world.

People with mental health problems can have difficulty sleeping, and one of the things that can keep them awake is that their mind won’t shut down at night. The wheels keep spinning. The depressed person broods, the anxious person worries. Yet even mentally “healthy” people can have this difficulty. Some of my most efficient days at work have resulted in my most restless nights, as my mind churns away at some unresolved issue. It can be interesting, but it’s not an ideal way of living at 2 AM, and makes me wretched company at the breakfast table.

And the more efficiently I work during the daytime, the worse the problem can be at night, suggesting the paradoxical conclusion that a life well lived is not overly efficient. We can get fixated on developing some perfectly optimized method of living, yet the method itself can turn into a druglike stimulus, a crystal meth-method that keeps us frenetically active and brimming with energy, yet insomniac and on the edge of burnout.

The most sustainable way of living, the one that won’t leave us sleepless and mentally wired, may be a kind of “productive inefficiency”.

When life is productively inefficient, things get done, and they get done well, yet we slow down enough during the day, and recover enough periods of stillness and quiet and “doing nothing”, that our mind knows how to slow down again and stop when it’s time to sleep. The productivity that’s “lost” due to inefficiency is offset by numerous small gains, like better sleep, lower stress, seeing problems from unfamiliar angles, and more attentiveness in our interactions with other people.

And we might recover something else, something almost spiritual: glimpses of the world through an unrippled mirror.

The clamor of cities

Two thousand years ago, the philosopher Seneca lived over a public bathhouse in Rome, and he complained about the noise of people doing workouts and getting massages:

When the strenuous types are doing their exercises, swinging weight-laden hands about, I hear the grunting as they toil away…and the hissings and strident gasps every time they expel their pent-up breath. When my attention turns to a less active fellow who is contenting himself with an ordinary inexpensive massage, I hear the smack of a hand pummeling his shoulders, the sound varying according as it comes down flat or cupped.

And that wasn’t the only noise. Throughout Seneca’s neighborhood he could hear ball players shouting out scores, and people brawling, thieving, singing in the bath, jumping into pools, tuning their instruments, selling sausages—and somebody yelling while getting their armpits plucked.

Seneca’s noise complaints are astonishingly modern. Something similar could have been written today by an apartment-dweller in New York or Madrid.

According to research, urban noise, like traffic, increases the risk of sleep disturbance, annoyance, depression, anxiety, suicide, and behavioral issues. In addition to the brain it negatively impacts other bodily organs, most likely due to chronic stress.

The noise of urban life, like speed, is another byproduct of civilization, and has become prominent only in the last two centuries—roughly starting in the 1800s—when the number of people living in urban areas began to sharply increase.

More than half of the global population today lives in cities, and that number will rise to almost 70% by 2050—and of these, 50% will live in cities with over half a million people.

Rome will be almost everywhere.

A culture of ambient distraction

The speed and noise of civilization—its shops and amusements, its shouting sellers and social interactions—has become faster and louder in the online realm. The collective mind of society has never been more distracted and obsessed with its own clamor.

We don’t just get preoccupied with what we see online, as we click from one thing to another, whether amazing or amusing or outrageous. We are practicing an altogether new state of mind, a weird between-state in the uncertain gap between the thing that is beginning to bore us and the thing that’s about to stimulate us.

It’s as if we’re stepping across a narrow gap between cliffs, again and again, with a sense of uneasiness. For some this abyss of distraction, and the feeling of uneasiness that comes with it, can be as much a feature of the online experience as the content we’re consuming.

Writing at the time of the Covid pandemic, Psychiatrist Jud Brewer described an “anxiety-distraction feedback loop”, where people turned to food, alcohol, social media, and TV as a means of coping:

Distraction is the modern day equivalent of avoiding the dangerous or unknown in ancient times. Uncertainty makes you feel anxious. Anxiety urges you to do something. In theory, that urge is there to drive you to gather information. Yet, when no new information about the pandemic is available, checking the news doesn’t make you feel better. Your brain quickly learns that distraction is a pretty solid alternative.

The problem is that, often, distractions are not healthy or helpful. No one can binge on food, booze, or Netflix forever. In fact, it’s dangerous to do so. You brain will become habituated to these behaviors. You eventually will begin to need more and more of them to get the outcome you’re accustomed to.

Distraction has always been a problematic coping strategy that can sometimes worsen the emotion it’s trying to quell. But in the Internet age, distraction is not just a way of coping but becoming a normative way of being. We are creating a culture of ambient distraction.

We take it for granted that students will be distracted from their studies, employees from their work, and even parents from their children; but the paradox is, while we’re all distracted, we’re mesmerized by distraction itself, even while it worsens our feelings of uncertainty. Ancient wisdom sought out the “still waters” of the soul, yet we’ve become compelled by the opposite, addicted to the anxious ripples of digital waves. Rather than “praying without ceasing” we distract ourselves without ceasing.

Much of this situation is, of course, by design. Distracting people is an industry. Corporations fish billions of dollars out of our inner disquiet. We live not just in a culture of ambient distraction, but of Monetized Ambient Distraction.

A mad culture, we might call it.

The uncomfortable quest for stillness

The urge to escape from stillness, to flee uncertainty and plunge back into distraction, can be irresistible. In the middle of writing this essay, working as efficiently as ever, I felt nevertheless a need to take a break. Yet I ignored this wise instinct and decided to print up a few paragraphs to review what I’d written. Somehow, there was a problem with the printer, and as I stood up in irritation and stepped away from the table to see what was wrong, the strap on my sandals snagged on a cord that was connected to the front of my box-sized computer and whip-snapped the machine off its pedestal, sending it crashing to the floor.

The message was clear enough. Slow down. Take a break. (Luckily the machine survived.)

Cultivating quiet is difficult, not just because we need to disrupt our usual routines, but because the experience of quiet itself can be uncomfortable. Research suggests that people would prefer not to sit in quiet and think, even for as briefly as 6 to 15 minutes. In fact, people would prefer to suffer electric shocks:

For 15 minutes, the team left participants alone in a lab room in which they could push a button and shock themselves if they wanted to. The results were startling: Even though all participants had previously stated that they would pay money to avoid being shocked with electricity, 67% of men and 25% of women chose to inflict it on themselves rather than just sit there quietly and think.

The gender difference might reflect the tendency for men to be more sensation-seeking than women. Overall, though, the results suggest that irrespective of gender, people don’t like to be left alone with their thoughts. Doing nothing is hard. It’s a struggle against many obstacles, from the buzz of civilization, to our addiction to technology, to our own human condition—and that hardly covers everything.

And yet many notable figures in history lived quietly, slowly or thoughtfully. As one commentator reminds us:

Socrates and Aristotle would philosophize best when on long walks. Descartes famously locked himself in a dark room just to think. Henry Thoreau wrote extensively about the need for long, rambling saunters in the woods. Siddhartha Gautama (the Buddha) meditated for six months (by some accounts) before he discovered his Four Noble Truths. In Daoism, only the slow and deliberate can be called virtuous, or a sage.

So, do we all need to be philosophers or Eastern mystics?

One of the challenges of living a slow-mindful-do nothing-sort-of-life is that it can sound so hackneyed and phony. Self-help experts can make six-figure salaries promising to transform our lives if we would only just focus on our breathing for twenty minutes a day, or some variation of that ancient method—while a recent systematic review of research found little support that practicing meditation improves happiness.

Studies out of the UK and Australia similarly found that students who underwent training in mindfulness didn’t emerge any healthier than peers who didn’t participate, and some ended up worse off, at least for a while. Another major study out of the UK found that meditation didn’t improve the mental health of children, or worse:

The results of MYRIAD, the most expensive study in the history of meditation science (£6.4 million funded by the Wellcome Trust), have recently been published. Over 8000 children, aged 11–14, were tested across 84 schools. The results show that mindfulness meditation failed to improve the mental health of children compared with a control group and that it might even have had a detrimental effect on those who were at risk of mental health problems.

Still other research suggests that in the short term at least, the benefits of meditation “are no different than those of similar stress-relieving activities and its potential harms are poorly understood”.

So, does all this mean that meditation is actually meh, or even suspect?

One of the first lessons I ever learned in mental and behavioral research is that “it depends”. People are different, and their environments are different, which makes it very difficult to generalize whether a certain technique or strategy is going to be effective (or harmful).

Mindfulness and other techniques involving prolonged quiet or stillness are probably helpful for some people, but not everybody, and maybe not even the majority.

It’s also possible we expect too much of such techniques. Many seek “transformation” or “enlightenment”, but maybe we ought to have humbler expectations about how much a person can reshape the imperfect human condition through individual mental effort of any kind, meditative or otherwise.

We’re offered hype, when humility and realism might do us better.

A semantic stillness

I’ve held off going into spirituality in this essay. Not all of the readers here are spiritual or religious, and those who are come from many different backgrounds. Still, it’s impossible to go far into the topic of stillness without brushing up against the sacred.

As a Christian I have a regular practice of prayer. This includes individual prayer and prayer with family. It’s been happening for so long that it doesn’t feel like an intrusion on the usual daily activities, but a seamless and ordinary part of life, much as washing dishes and doing laundry—although it’s profoundly different, of course, in many ways.

What happens during these prayers?

There are two sides to this question. One side is the eternal—which is God, or Absolute Reality—and the other is the human side—the people who are praying. I’m not going to talk about the eternal side, as the focus here isn’t on the supernatural.

On the human side, certain elements of prayer can be translated into non-religious language. These elements shouldn’t be confused with the whole of Christian prayer or faith, which is fundamentally not an abstraction nor reducible to concepts and principles. These elements can be helpful, however, in understanding the ordinary mental and social processes that are involved in prayer, and how they overlap yet differ from secular meditation:

The elements include:

Silence. Prayer, like many sacred practices, involves a period of silence or quiet. This can be as brief as a few seconds or as long as a few minutes (for monks and other monastics, it can be much longer).

Semantics. Prayer isn’t just silence, but it’s a particular kind of silence—a semantic silence, we might call it. That means it involves language and transcendent meaning which gives a particular shape to not only the prayer, but the mind of the person praying—their hopes and understanding about their lives and the universe. Some prayers are formulaic, involving the repetition of memorized words, and others are more spontaneous, but either way, language is an essential part of prayer.

Relationships. Prayer is rarely just an individual thing, but is often done with others, whether a spouse, a family, or a community.

Obviously, silence, semantics and relationships are elements found in many religious practices outside of Christianity. At the very least, the ubiquity of these elements suggests that, whatever we might personally think about religion, people going back thousands of years have understood that cultivating a good life, one that includes stillness and quiet, must be interwoven with sacred meaning and human relationships.

It’s possible that secular and therapeutic meditation practices have failed because they focus too much on stillness and quiet, and on the individual, and not enough on meaning and relationships. In fact, mindfulness practices typically discourage an individual from holding onto any specific thoughts or ideas during the practice. Instead, the practice is to let go of all thoughts (and feelings and sensations). But over time this might inadvertently weaken a person’s values and beliefs, including the positive ones, or disrupt their sense of mental coherence and leave them feeling worse off, as suggested in some of the research above.

Again, this isn’t to say that meditation is never helpful for anybody. But it does suggest that the decision to spend a period of time each day cultivating a practice of stillness shouldn’t be adopted lightly or formulaically, but with consideration for an individual’s personality, beliefs, unique background and circumstances, including their spiritual needs.

As urbanization spreads, so will the clamor and speed of civilization, and the mad culture of Monetized Ambient Distraction. We can’t imagine where all this will lead, any more than Ötzi the Iceman could have imagined taking a selfie on a smartphone or driving a Tesla through Times Square. Yet we know the clamor is getting louder, and the hum of distraction is almost constant. We need stillness and silence.

We might wish we could flee to a place like the Alps, where Ötzi wandered among trickling streams and wildflowers before he died, at a time when the world was younger and quieter. But we are here, in the great engine, and here is where we must create our ponds of stillness.

And maybe some mountains of silence.

What is your practice of silence, quiet, or slow living?

Is there a role for language and meaning in your practice?

Where do other people fit in? What else is included?

Links and Further Reading

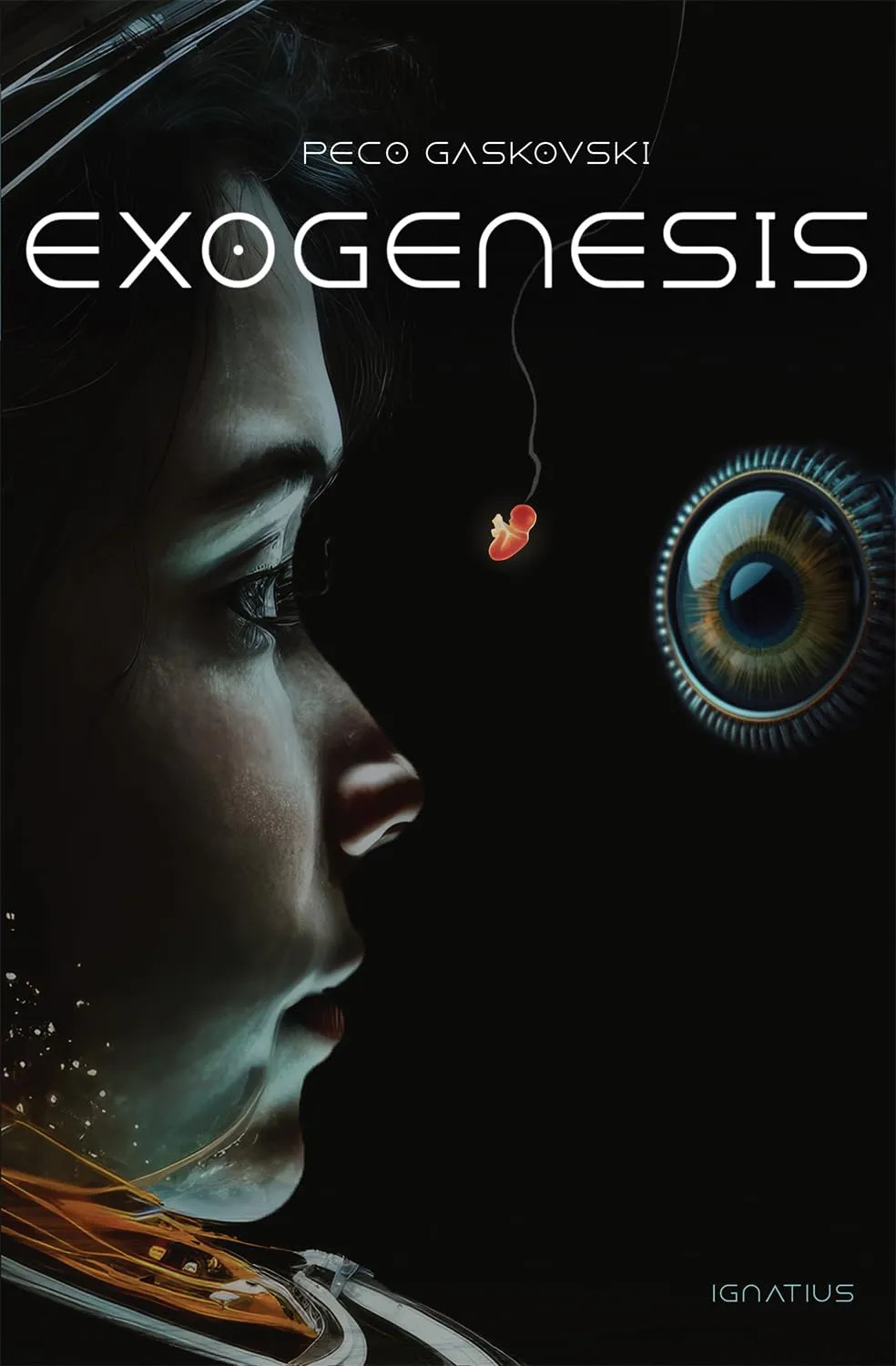

If you enjoyed this article, you can support my writing by buying and reviewing my novel Exogenesis (of course you can become a paying subscriber too if you’re feeling generous). Exogenesis is available from the publisher Ignatius Press, the Unconformed Bookshop, or at various other booksellers. Reviews here.

- ’s Substack Stillness in the West, though currently quiet, has a lot of great essays on the subject of prayer and stillness.

In The Midst Of The Blissful Silence and The Burdens of Speed by

- writes from the perspective of T’ai Chi and the slow and embodied life.

- has a forthcoming book, Reclaiming Quiet (out on Nov. 5th and available for pre-order), which “is an invitation to discover the profound, daily joy of resisting patterns of anxiety and hurry and cultivating a life of holy attention instead”.

- has some ideas on how to slow down in Gaining Time Through Wasting It.

- recently wrote about the folly of consuming too much news, and wonders if “chugging round after round of this limbic cocktail of dread and disgust might be bad for our mental health—maybe even our souls”.

- ’s remarkable essays include many reflections on prayer and the sacred, such as wild saints, plus a whole series on holy wells in Ireland, which highlights another element of prayer: place.

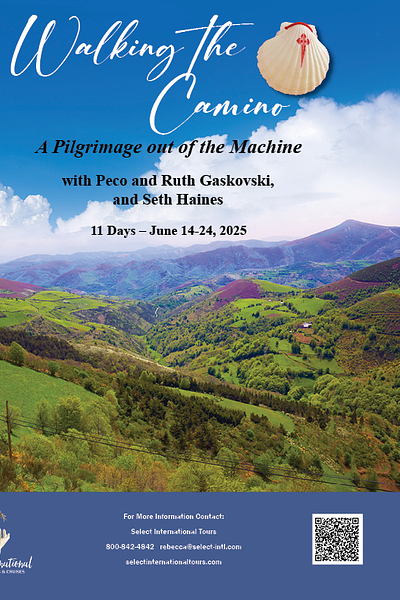

Come and join us on the Camino!

If you would like to step away from “a mad world” and follow the footsteps of ancient pilgrims, come and join me, my wife , and on a pilgrimage in Spain next year in June 2025.