And the Winners Are....

Congratulations & a bouquet of short stories

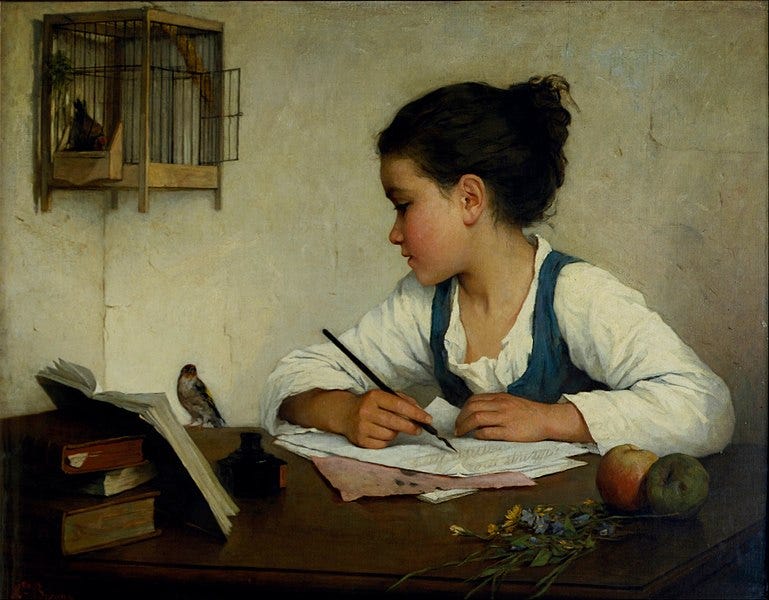

If you want to change the world, pick up your pen and write.

Martin Luther

Today’s post is dedicated to all the young writers who participated in the Young Writers Against the Machine Short Story Contest. At the end of May, I published Raising Writers Against the Machine in response to the rise of AI word processing tools encroaching on our ability to independently use language with accuracy, authority, and creativity. And thus by extension crumble what makes us essentially human — by abdicating language, we abdicate humanity.

As a homeschool educator I have my eyes trained on the younger generation, which needs to be equipped for living a life grounded in reality in an overbearing Machine age. It will take deliberate rejection of practices that remove us from our basic humanness and a fierce and purposeful engagement with counter-cultural practices. Such as writing. Creating rich, unique, and specific language grounded in reality has now entered the counter-cultural realm.

Read my whole post here.

To put my words into action, I invited young writers to harness their language skills, apply their minds, and invest their hearts by writing a short story set in nature.

The response was tremendous and entries arrived from all over the U.S., Canada, and internationally. The short stories were anonymized and uniformly formatted to support impartial judging. They were evaluated based on creative language use and story-telling ability by volunteer judges who are experienced writers or teachers ( a special Thank You to fellow substack writer Denise J. Hughes!) Thanks also to my husband Peco who, while not participating as a judge, helped by collating and anonymizing the entries.

The stories went through three phases of judging, and final decisions were challenging and in some cases very close. All that to say, these young writers have wonderful creative abilities and I would like to encourage all participants to continue honing their skills and sharing their talents!

And now without further ado….

Winners - Older Category (age 13-16)

1st Place - The War Machine - by Grace Jumper, North Carolina

2nd Place- SUSAN - by Leela A. Kingsnorth, Ireland

3rd Place - The Myth of Life - by Carina Fiorella

Winners - Younger Category (age 9-12)

1st Place - An Odd Setting - by Claire Evers, Ontario

2nd Place - A Bird’s Eye View - by Mary G. Lane, Virginia

3rd Place - Forest Girl - by Oriana Wasmund, Ontario

Awards

The awards for the Young Writers Against the Machine Contest have been generously donated by ICG Bullion, and in the spirit of tangibility and tradition will be paid in 1 oz .999 silver coins1.

Note: 1st place winners and runner-up of both categories are published below. You can view the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd place winners in a pdf format here.

Please note that the stories are the property of the authors and may not be copied or published without the author’s permission.

If you would like to support these Young Writers Against the Machine, please share and restack to spread their stories. If you enjoyed this post (or found it hopeful) consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a ‘like’.

1st Place Winner- Older Category

The War Machine

by Grace Jumper, North Carolina

The Machine came to the carefully hidden door of her secluded cabin in the woods in the form of an injured soldier boy.

On a brisk spring morning, she woke before dawn, as she always did. Everything was quiet, except for the occasional trill of an early bird or the rustle of some small creature in the woods. Savoring the peace, she grabbed a wooden bucket from its hook on the wall to draw water for her morning herbal tea. When she opened the door to go to the well, she gasped in shock.

There was a bloody boy on her doorstep. "Help me," he begged. "Please help me."

Reflexively, she almost slammed the door and ran to sound the alarm for the forest's inhabitants. The boy wore the gray soldier's uniform of the Machine, that terrible thing that she and her fellow forest folk had hidden from for over two generations. She should never consider inviting it inside her refuge.

This boy wasn't the Machine, though. Looking at him, bloodied and torn, she saw only a casualty of it. Rousing the forest would be unnecessary. She helped him inside and laid him on her table, the huge oaken one her grandfather had made for her parents before the Machine took them in the Spring Uprising of ’28, over 20 years ago. She began gathering the herbs, roots, and other remedies she would need. "How did you get here?" she asked, suddenly realizing that her sanctuary could be compromised.

"Animal trail," he managed. "Never would've seen it if I wasn't crawling."

***

His recovery took days. She woke earlier than usual every morning to take care of her chores and forage herbs for his healing. As she treated him, she couldn't help but notice the marks of the Machine on him, branding him as a foreigner to the forest. He had the lean-yet-muscular form of a soldier, and at the nape of his neck she could see the bleeding, festering area where his identification tattoo had been. He must have dug out his identifying code chip.

The Machine instituted a code system in ‘23, claiming commerce and identification would be easier without the use of repetitive and confusing personal names. The foresters knew that the chips also gave the Machine unlimited access to their location. Now that the chip was gone, she didn't have to worry about being found.

Even though she had been treating the boy's injuries, they became infected, and fever took him. He raged and sweated for days, struggling, and murmuring in a restless haze. Occasionally, his babble became tortured cries. What scared her was when she could make out words–words about monsters, and wars, and about comrades lost. She had to grit her teeth, having no choice but to listen as she sought to combat the infection and fever.

***

Ten days after the soldier had shown up on her doorstep, summer dawned. She woke the morning of the solstice to find him awake, with his fever gone. "Good morning," she said.

"Where am I?"

"In the forest," she answered carefully. "You're safe now."

He sank back, too weak to respond. His eyes darted to the windows and doors; clearly, he didn't feel safe. She didn't know how to counter his fears, so she decided to let the forest do it for her.

Once the boy could walk, she helped him outside to let the forest lift his spirits. He was on edge at first, but before long he was smiling at the sound of birdsong and pointing out the healing herbs she had taught him.

With time, he no longer wore the Machine’s influence like a scar. He grew enamored of the forest, and on warm nights they climbed the tallest trees to watch the stars appear in the sky. One such night, she broke the tranquility of stargazing to finally ask the question that had been begging for an answer. "What happened to you? How did you become separated from your regiment?"

His expression darkened. "They declared war on the forest savages in the foothills up north." He faltered. "I was drafted against my will. On our march through the woods, we were ambushed. It wasn't a large party and we managed to defeat them, but then…." He closed his eyes and shuddered violently. "Then the monsters came."

"Monsters?" she frowned. "There's no such thing."

"There were." His words came out slower and slower, as if he were speaking through quicksand. She could see the torment in his eyes. She wanted to tell him to hush, to forget the terrors he had seen, but the overwhelming need to know silenced her. "They came out of nowhere, unlike anything I'd ever seen. It was a slaughter. I only survived because I hid after being wounded in the first attack. Like I said, I couldn't have found the trail to your cabin if I wasn't crawling."

Neither of them spoke until they were inside again.

"I need to go back," said the soldier boy.

"Go back? To fight monsters? You're not in any condition for that."

He shook his head. "I need to see if anyone survived. Maybe some of my friends are still there. It's my duty."

She knew she couldn't let him go by himself. He didn't know the forest; it would be too easy for him to fall prey to wild animals or to get lost.

The next day, she packed bundles for each of them and they set out to find the site of the skirmish.

***

It was less than a half-day's walk to the battlefield. Amidst the deep green shadows of the trees, she could smell the blood and rot on the breeze, layered with a stench like animal musk. She gagged, and the soldier boy looked pale. "That's what they smelled like," he whispered.

The pair dropped onto all fours and crept into the underbrush, moving with the slow stealth of wild animals over dead leaves and twigs. Eventually, they reached a point where the repulsive reek was overwhelming. A thin screen of foliage provided them with cover, but also allowed a view of the battlefield.

Bodies were everywhere, mutilated in ways that could only be done by some sort of animal. The amount of butchery was on a scale that she had never seen in the natural world; it more resembled an abattoir.

She was about to step onto the battlefield when she heard a rumbling growl. Behind her, the soldier boy froze as something stood from where it had been lying amidst the bloodbath, hidden among the bodies.

It was built low to the ground and longer than any animal she had ever seen, with a mangy black pelt that revealed putrefying skin in patches, but that wasn't what was most disturbing about it. It was too irregular. Its body parts were out of place. It had four legs like most mammals, but they were slightly different lengths and weren't quite in the right places. Numerous eyes were positioned slap-dash across its bloodstained face, and when it yawned, she saw row upon row of serrated teeth crammed against each other.

More of the monsters rose out of the ground until there were more than a dozen of them. They ranged through the battlefield, devouring the remaining flesh of the dead with sickening gluttony.

These were not the sort of predators that she would expect in the woods; the soldier boy was right. These were monsters, unnatural, like nothing she could even imagine.

She turned to whisper that they should go back, but the boy's eyes were widening. She turned back to the scene and gasped.

The creatures were now standing on their hind legs, shaking their bodies. Their disgusting hides fell away, changing them from monsters to men. They wore uniforms of gray, blue, gold, and silver, resplendent with medals and ribbons and braids and other decorations. Everything about them was natural, except that they were bloated from gorging on the slaughter and had blood crusted around their mouths.

The men cast their gazes over the battlefield and, to her utter surprise, began to wail. "Oh, the horrors!" they keened. "Oh, the ugliness of the enemy! How dare we let them get away with this! We must not let them! We must not let them destroy any more of our youth! To war! To war!"

They wailed for a few more moments before trailing off and grinning at each other with sick, dishonest smiles. Then they wiped their mouths and mounted the horses that awaited them, riding off without a backwards glance at the bloodshed.

"What were those?" she asked once the creatures were out of sight. Her stomach was roiling, and she was sure she was going to vomit. She turned to crawl out of the underbrush and away from the carnage, but the soldier boy didn't move. His eyes were trained blankly on the battlefield.

"Those were my commanders."

2nd Place Winner - Older Category

SUSAN

by Leela A. Kingsnorth, Ireland

—England, 1831—

It was here in this garden, years ago, that she had first told her mother about him. She had thought that the flowers might soothe the older woman, bobbing their heads and laughing at their conversation. She had said things like, mother, don’t take on so— you knew one day I would leave here, and marry, and make my own home. I think he is the one, the right one for me.

But even as she had spoken it seemed that the moving hollyhocks were shaking their heads instead of nodding, as if they heard her words for what they were— parroted phrases, things people said in stories, because she did not know how to explain to her mother how it really was. Mother, she should have said— I can hardly bear to leave you in this great lonely garden. But I must go. And I could not pull you with me— I could not uproot you from the place your family has grown for so long. I am a young plant— I can be repotted, and I must be, else my roots will circle the pot and press against the sides and I will be moulded into the shape of this tiny world I know.

So I must go. But you, mother— you are an old plant now. You have lost your blossoms. You have not many seasons left to see, not many more rainfalls. Your pot is part of you— you could not survive being ripped from it. So you must stay. That was what she should have said.

That was how we would have told her, said the hollyhocks.

It was here in this garden, long ago, before even that, that he had begun to poke fun at her, before they were married, before she left these flowers to grow alone.

He had been quiet awhile as they walked, and she had been hoping he might compare her to a flower— she was taking care to walk very slowly, as if bobbing in the wind. He stopped suddenly, and pushed a flowerhead at her.

‘Look, Sue,’ he said, ‘this one’s you. Didn’t they used to call you Black-eyed Susan when you were little, you got into so many scrapes?’

Black-eyed Susan? That flower!

She had pretended to be angry, so she could hear him say sorry with a smile, as if he didn’t really mean it.

It was here in this garden, just after that, that she had told her closest friend, her only friend, everything— every word, every joke he had ever said to her, as if she needed to prove to someone that he was the right one.

‘Look! He said I was this flower!’ said Susan, pushing the big, dark, daisy-like head of it at her friend, laughing.

‘That one! You’ll marry him?’

‘If he stays alive! He said he might die of joy before then. Him and his jesting. He’d better not!’

‘Whatever would you do if he did die?’ this question seemed to Susan suddenly serious, and the flowers slowed their bobbing.

‘Lord knows... but I’d die, too, most likely! I must.’

She stood here now, years later, and thought— It was this garden he must have run through that night last month, to the meeting in the woods.

‘I must go, Sue,’ he’d told her, using the short name she said sounded like a pudding, and would let no one else call her by. She looked at him, the man she had married when he barely was a man, now the father of her daughters, and saw no laugh in his eyes. He was not jesting. He had stopped jesting the winter before, the winter the big farm hadn’t needed him to thresh the husks with his flail, the winter the house was cold and the food thin.

‘I must go. We promised. We promised we wouldn’t stand by and starve.’

His words— were they real? Could they be? He sounded like a storybook hero.

She hadn’t stopped him. How could she have? She needed him to fight. She knew the fight was her own fight too. When the rioters met in the woods and planned, when they stumbled at night to the farms and broke their way in— it was for her and for her daughters. Every threshing machine they smashed or set alight— every match struck and spade brought down.

He had said more things, trying to convince her— that next winter they would not want him and his flail, they would not pay him for threshing their husks— that it would be even colder and hungrier than the last. That the machines, those great cold metal things, would do it faster and cheaper than he could. But she already knew this. And before he’d even told her— she wanted him to go.

He must have run through this garden, then, her maiden garden, where they had met, that night, with his heaviest pitchfork.

She stood here between rows of defenceless flowers, and she was angry now. It seemed to her that the threshing machines loomed on the horizon of her country, of her garden even, cold and efficient and faster than a man could even be. It seemed to her, and in her dreams, that there were many more machines, huge ones, huger ones, behind them, and they could do things better than any man who was made merely by God.

She was angry at the newspapers who shouted that the rioters wanted blood, when she knew them, when one had been her own husband, and they had not yet hurt a human soul. She was angry at the farmers for loading guns, and angry at the farmer who had shot that shot, and angry at the smoke for obscuring a shot meant to scare so that instead it hit a man.

But she could not be angry at that man for being there. If it were not for many things, she would be there now.

She wanted it to stop, sometimes—all the colours and the voices, everywhere, too many, the voices of her friends, of her daughters, speaking or silent— even louder when silent, looking at her, waiting. They all wanted her to talk back and notice them and she needed silence. ‘Susan!’ they said, ‘Susan, Susan, Susan!’

—and all she could think of was the grave he lay in now, and it was a yew tree above it— and he loved yew trees, had nearly died eating the pips once as a boy, and now it was guarding him, so it would be all right— but the grave was small, narrow, and would there be space enough for all of them, when the time came? And her mother, her mother was lying alone— near the river she liked, but alone— who would lie with her? There was nothing worse, nothing, than waking up in the night and being alone in the cold and not daring to call out... lying alone with no one beside you... if they woke up now, they would be alone... there was nothing worse in the world, and every night when she fell asleep now she was afraid of waking because she knew she would forget, and find herself alone in the dark...

‘Susan,’ they would have told her, all the noisy women, ‘Susan, Susan, Susan! Bring your daughters with you. They need you... and you won’t be alone, then, if you wake...’ but Susan saw that they didn’t understand, they couldn’t see that she could not stand to hear her daughters mewling, no, not now, later— later she would turn back to them, all of them, and smile and answer their questions and cook and resolve the arguments of the girls, but not now. Not now— now, today, she needed silence, silence and the flowers.

...But she could not stop it, feeling or seeing or listening, even when she wanted to the most.

What will you do? asked the hollyhocks, knowing the answer.

‘Lord knows,’ said Susan. ‘But I must live.’

Yes, said the Black-eyed Susan, always— and the wind moved it up and down like flames.

HISTORICAL NOTE—

The better-known riots in England brought on by the industrial revolution were carried out by the Luddites — textile workers attacking the new industrial looms.

Years later, in the 1830s, there was another series of riots, these ones agricultural, carried out by the ‘Swing Rioters’. The rioters targeted the threshing machines that were replacing their handheld flails and robbing them of winter employment. They spread from Kent across the country. Hundreds were caught and put on trial—many were deported and several executed.

-“Rioters were usually young men, many of them married, therefore they may be deemed to be stable and respectable.” -“Only one person is recorded as having been killed during the riots, which was one of the rioters by the action of a soldier or farmer.”

I could find out nothing else about him, even his name.

1st Place Winner - Younger Category

An Odd Setting

By Claire Evers, Ontario

Joan, a bark brown pullet with downward facing tail feathers, scratched in the dirt for bugs under the blueberry bush. Her neck was penciled with black, and her feet were adorned with slate blue scales, smooth and similar to a pinecone’s closed pods. Suddenly, she stopped pecking when she heard Amy, a flighty pullet, chirp to her. “The rest of the flock are exploring the rocky hill, seeking to destroy slugs, and hornworms. I waited for you, to show you a place no bird has ever explored. "Want to come?” Joan nodded her head, then followed Amy as she flapped towards the shed, chirping to her all the while.

“Do you know that big hole, under the log?”

“Yes, I do.” Joan replied. “Well, what if we explored the hole, and came back with an amazing story!" Joan figured that was a fun idea, so they slipped into the hole and found themselves in utter darkness. Joan couldn’t see very well, but the dank, humid, earthy air made her wish to be back above ground, in the warm sunlit forest clearing that the flock inhabited.

The clearing had a few bushes, their branches sagging with the weight of rotund blueberries. There was a large amount of lush green grass, and the air was light. A sweet fragrance wafted from the blueberry patch which grew beside a squat, gnarly Crab apple tree with thick branches. The flock roosted on this tree and feasted on the rocky hill that teemed with greens and pests. A shallow stream trickled off to the clearing’s left, providing the flock with spring-fed water.

Amy nudged Joan, snapping her out of her thoughts, and they continued down the tortuous tunnel that led into a badger’s sett! The ceiling, floor and walls were woven with pond reeds, perhaps the ones that grew around the stream. The sett was warm, lined with black and white tufts of fur, while a pile of large grubs wiggled in a corner.

Joan and Amy each grabbed a grub, then climbed back out the tunnel. It was perfect timing because the flock was looking for them. Joan and Amy flew-ran towards the flock. Then, they told them about the grubs in the Badger’s sett. Most of the pullets squawked joyfully at the thought of easy access to grubs. However, the hens and roosters on the Council of Elders all disagreed. They shivered at the thought of what would happen if the badger came back while the chickens were in the sett.

Harriet, a pullet of the same feathering as Joan thought it was best to listen to the Council of Elders. Besides, Harriet had a queasy feeling, like she’d regret going down the tunnel. So, she informed Joan: “I’ve got a bad feeling about this, and I don’t think we should go back there.” All the pullets laughed at her.

“What could go wrong?” “All we want are plump, juicy grubs whenever we are hungry.”

“What would happen if the badger came back while someone was in its sett?” Harriet asked. “We’d all be badly clawed?”

Marie answered. “Oui. Il y a toujours un risque avec les aventures”.

“Speak English!” Amy scolded Marie, forgetting she was talking to the Head Hen of the Elder’s Council.

“Mais, je suis venue de la France!” It was true, for years ago, Marie, a Bresse Gauloise chick, was imported from Normandy. At that time, the current eldest of elders had been chicks. They lived nearby, tended by a human living in a hut. The hut had burned to ashes and the chickens had to flee. Marie had discovered the two acre clearing with the Head Rooster where the flock now lives, wild and safe.

The next day, everyone woke up early, even before the roosters crowed. Amy and Joan begged and pleaded with the Elders to allow only four pullets to travel with them to the sett just one time. The Elders acquiesced, with the condition that they would chose the pullets. They chose Guillaume, Angelica, Frieda and Harriet. Harriet’s peers laughed at the fact that Harriet didn’t want to go down the hole.

“The elders even chose you, weirdo!” a plump pullet chirped, giving her a glare. Some of Harriet’s peers encouraged her to come, telling her that this was the opportunity to enjoy “the experience of a lifetime”. Others teased her

“Well, I guess when you get hungry, you’ll have to find your own food”.

In the end, Harriet came slowly, dragging her talons. The musty black tunnel to the sett twisted and turned. Every noise echoed through the tunnel, bouncing back to the pullets as a cavernous, ear-shattering bellow. Harriet shivered, closely following Amy and Joan. Finally, they reached the Badger’s sett. Amy went into the sett to grab a grub, when a roar echoed through the tunnel.

A pair of sharp claws sliced through the air, missing Amy by a feather’s breath. The badger bristled and bared his teeth. He growled threateningly and shot after the pullets. As he ran, the sounds of his paw steps vibrated the earth. The pullets immediately turned tail and flapped frantically back up the tortuous tunnel. They shook and squawked in a series of high pitched tones, discarding masses of feathers. This temporarily blinded the badger who continued to swipe at them with rage. Thankfully, the birds reached the opening of the sett and flew back to the clearing. At this point the badger, breathing heavily, retreated and lumbered back to its sett.

Some of the pullets remained uninjured but Joan, Amy, Harriet, and Guillaume suffered deep wounds and were missing large clumps of feathers.

One year later…

The crowd of brown chicks began to peep once Harriet finished her badger story. Citrus, the youngest, asked Harriet a question: “Was that just one of those you must obey your elders or else stories?” Harriet replied.

“I’m an elder, and I didn’t make this up. See Guillaume? The claw scars on his leg are from that badger.” Citrus was silent for a moment before peeping anxiously:

“Well, I hope nothing like that ever happens again.”

“It most likely won’t.” Harriet assured him. “New members to the Elder’s Council are carefully chosen by the wise Head Hen and Rooster. As the Head Hen, who was picked by the great Marie, I’ll try my best.”

THE END

2nd Place Winner - Younger Category

A Bird’s Eye View

by Mary G. Lane, Virginia

I only slightly remember being in the egg. I remember the dark warmth that made me constantly sleepy. I remember growing so big I felt my egg was a prison instead of a shelter. I wanted to get out, although I did not know what lay beyond. By pecking on the eggshell as hard as I could, I managed to emerge halfway out. What a dazzlingly bright world greeted me! So big, so wondrous, so terrifying. I strained until I broke the remaining eggshell in half. As so as my shell was broken, I wanted to creep back in.

I cried out in a startlingly high voice. I was so surprised by the sound of my cheeping that I almost fell onto another egg. Feathery comfort surrounded me at once, and I knew instinctively that this was Mother.

There were three of us baby birds: I, a female, and two males. I was the eldest because I had hatched first. My mother looked us over and spoke to each of us. “You are ‘Leaf,’” she told me. “Because you are so little and light. Your brothers are ‘Twig’ and ‘Sunshine.”

We became fast friends, the three of us. We learned to cry out for worms and bugs when we were hungry. We learned to snuggle up to Mother at night. We learned to sing like Mother, sweetly and happily. And we learned it all together.

Twig was the first one to venture out of the nest. He was the bravest and the most eager to see the world beyond. As soon as he was on the branch, he toppled over, squawking. I don’t know what would have happened if Mother hadn’t caught him. But he tried again…and again…and again until he could sit there without losing his balance.

One day something happened that changed my life. We were all sitting on the branch, arguing about whether beetles tasted better than worms, when, out of nowhere, Mother came flying toward us from behind. We fell off the branch. I was terrified! Then, all of a sudden, I found I was going up again. My wings were flapping and I was flying! Up nd around I flew, cheeping and singing until I was exhausted. I went back to the nest then.

“Mother,” I asked later. “Why did you come flying at us like that?”

“Because you needed to learn to fly. I knew it was time and you were ready.”

“Why not wait until we say we’re ready?”

“You would have been too scared to ever try. You need to be ready for the Journey in Autumn.”

“What’s the Journey?” Twig interjected.

“The Journey is when all the birds fly south in Autumn. They fly back north in Spring.”

We learned to fly very well in the course of the next few weeks. Mother taught us how to search for worms, bugs, and seeds to eat. Then she told us it was time for her to say goodbye.

“You are grown birds now,” Mother said. “It will be Autumn soon. Go where your instincts take you. Goodbye.”

We were sad when Mother left, but we were excited for the Journey. We all felt a chance in the air that compelled us to fly south. First Twig, then me, then finally Sunshine spread our wings and began the Journey. We stopped to rest every now and then, sometimes on trees and sometimes on strange, black cords that hung high in the air. We saw loud, growling metal beasts all over, especially on the black strands that broke and wove together all over the landscape. What strange things we saw! Strange plants and big blocks that humans went in and out of.

“Maybe the humans’ nests,” Sunshine mused. Mother had told us all about humans before she left, and about their loud noises and odd ways. We soon came to a nice warm tree in the South, and there we knew to stop.

“We have come far enough. Let’s winter here,” I said, and we did. The beautiful tropical plants delighted us, and we enjoyed our winter so much we decided to come here every year.

In the Spring we flew back to our old tree, and there, on a branch, I saw something so strange and wonderful I almost fell over. A handsome young male robin sporting a scarlet breast. He strutted. He sang his love. He told me is name was Sunset the Great.

“The Great? What do you mean? I asked.

“Okay, fine, just plain Sunset. Because my breast is so red and handsome,” he added.

Sunset was a show-off, but everything he said about himself was true. We decided to mate. We built a nest together, placing every twig or ribbon or piece of hair together with tender care. I laid eggs, he brought me worms, I warmed the eggs, he warmed me with his feathers at night. Soon the eggs hatched.

Now I watch my babies sitting on a branch. I know now what my Mother meant. I know that Water, Wind, and Rose, are ready to fly.

The End.

If you would like to support these Young Writers Against the Machine, please share and restack to spread their stories. If you enjoyed this post (or found it hopeful) consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a ‘like’.

Each coin has an estimated value of $30 US dollars. The silver coins are from Canada, the U.S., Austria, Australia, and South Africa.

I much enjoyed reading these stories, and am glad to know that there were many more entries. The knowledge that there are many young people still free and able to use their minds in this creative way is really heartening. Thank you for organizing the contest!!

Thank you so much for giving our youth the opportunity to express their love of nature and freedom through the creative writing process, Ruth!