The 3Rs of Unmachining: Guideposts for an Age of Technological Upheaval

"The Look of Silence", a scandalous proposal, and a practical beginning

Today’s post is a unique collaboration between my husband Peco and I, capturing our efforts to point a hopeful path through an age of technological upheaval. Although this is a single (lengthy) post, we have been discussing the foundational ideas for over a decade. We hope that you will find encouragement and practical catalysts to help you on your journey.

For those of you who, like me, prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, I have converted the post into an easily printable pdf file. Remember to come back and share your thoughts and comments! You can access the file here:

The 3Rs of Unmachining: Guideposts for an Age of Technological Upheaval

A five-minute drive from our home (or thirty minutes by horse and buggy), lies a small town with a Mennonite “Country Pantry”, where the price of 20kg bags of unbleached local flour is noted on chalkboard, dozens of fresh loaves of bread are baked daily, customers’ tabs are written neatly in a little black notebook, and ice cream cones still cost $1.50. Esther greets us cheerfully and asks how we have been keeping. As we chat, I (Ruth) cannot help but ask about the rules around cell phones for Mennonites, as I noticed that they at times make an appearance in the palms of some of the occupants of the horse buggies. She explains that each fellowship sets their own rules regarding cell phone use, but that they always do include strictures around filters.

“Do you have a cell phone?” I ask.

“Oh, no!” she smiles.

“Do you ever miss not having one?”

“I wouldn’t know what I am missing”, she laughs “at times I think it might be convenient, but we always find a way to make do without it.”

Inwardly you may have the same thought that occurred to me: You are not missing anything.

Even though Esther and I were over a century removed from each other in the modern conveniences we choose to use, we shared the same conviction that technology is making us less human.

“We all want progress. But progress means getting nearer to the place where you want to be. And if you have taken a wrong turning then to go forward does not get you any nearer. If you are on the wrong road progress means doing an about-turn and walking back to the right road and in that case the man who turns back soonest is the most progressive man. There is nothing progressive about being pig-headed and refusing to admit a mistake. And I think if you look at the present state of the world it's pretty plain that humanity has been making some big mistake. We're on the wrong road. And if that is so we must go back. Going back is the quickest way on.”

from Mere Christianity by C.S. Lewis

Although Lewis penned this quote in reference to Moral Law, it seems to capture the current moment perfectly: somewhere in history we took a wrong turn on the road of technology, and it’s time for a course correction.

The problem is, nobody seems sure where to turn. Do we go back in time and, like the Amish or Mennonites, draw a bright clear line about what technologies we accept into our lives? Should we all become digital “minimalists”? Should we move away from the cities, and seek refuge in nature?

Of recent technologies none have thrown us off course, none have penetrated the human mind, so profoundly as digital devices. We’ve all experienced this penetration in different ways. No relationship, no intention or goal, no commitment in our lives, no appointment, no schedule, no conversation, not even God, is sacrosanct when we’re in front of a screen, or near a screen, or just thinking “Where did I put my device?” Our mental awareness and concentration—the very essence of human consciousness—drifts toward our screens, as if carried on an irresistible breeze. As if we are all turning into mere feathers, floating on the breath of Big Tech.

Almost nothing in life escapes this intrusion on our minds. We see it everywhere, from our homes to our institutions, and it happens in every age group. A steady irresistible push has conditioned us to accept that portable, digital technology is an indispensable oxygen required for all aspects of our daily lives from coupon savings to choosing a dating partner, from social affirmation to soothing babies with screens in their cribs.

But if we need a course correction, then where? What is the turn in the road that—if we make it—could spare us from the negative impact of technology, keep us rooted in reality, and deepen what it means to be human?

Most importantly, this turn should be so fundamental that it can be followed by anyone, irrespective of whether they live in a condo tower in Toronto, or deep in the northern forests, and span the “ecumenical trenches” of religious belief, or even non-belief.

This sounds like quite a big promise. Yet, we are not suggesting a complete solution, but instead have outlined three essential guideposts that may help reorient us toward embodied reality, face-to-face relationship, and living more fully within our human parameters. It is so basic, we decided to call it the 3Rs of Unmachining.

Guidepost 1: Recognize

“And in the naked light I saw, Ten thousand people maybe more

People talking without speaking, People hearing without listening

People writing songs that voices never share, No one dared

Disturb the sound of silence.”

from “The Sound of Silence” by Simon and Garfunkel

Recently we drove along a busy stretch of road, bustling with university students making their way from fast food plazas to the campus. As our car came to a halt, we looked over at the bus stop. There were around a dozen students waiting, each had their head bent toward their device. We had been listening to a Simon and Garfunkel CD, and as lines of The Sound of Silence resounded, they were displayed for us in a living tableau. Our 11-year old commented that it was “The Look of Silence”.

This scene reflected perfectly the observation of Father Martin in

’s The Benedict Option, that many people’s faces seem vacant:“When the light in most people’s faces comes from the glow of the laptop, the smartphone, or the television screen, we are living in a Dark Age…They are missing that fundamental light meant to shine forth in a human person through social interaction…Love can only come from that. Without real contact with other human persons, there is no love. We have never seen a Dark Age like this one.

We have both written extensively on the negative effects of digital technology on our minds, relationships, and human fabric (see for example From “Dark Flow “ to Crossing Wendell’s Bridge and From Feeding Moloch to Digital Minimalism). It is sobering to recognize the effects1 of the substitution of embodied social interaction with online simulated connections:

73 % of Generation Z sometimes or always feel alone.

71 % of heavy social media users report feelings of loneliness.

School loneliness increased between 2012–2018 in 36 out of 37 countries and was high when smartphone access and internet use were high.

The loss of social connection triggers the same system as physical pain.

Time spent on social media is a significant predictor of depression for adolescents.

66% is the increase in the risk of suicide-related outcomes among teen girls who spend more than 5 hours a day (vs. 1 hour a day) on social media.

In the “race to the bottom of the brain stem”2 children are the most vulnerable contestants. Their minds are part of a relentless digital colonization. What is particularly disturbing, is that their understanding of human relationship is warped into a manipulative, disembodied competition for social status3.

In our digital relationships we share snippets; we are atomized, never fully human. We avoid dull moments, boredom, the tedium of life. When we meet people in real face-to-face encounters we falter in moments of silence and reach to the phone to share a meme, or take pictures of each other with funny filters.

In our virtual, curated social selves, we are never fully known.

O Lord, you have searched me and known me. You know my sitting down and my rising up; You understand my thoughts from afar off. You comprehend my path and my lying down, and are acquainted with all my ways.

Psalm 139, 1-3

Who we are depends on who is watching us4—and who we are watching. This basic aspect of human experience begins at the moment a mother begins breastfeeding an infant, in their mutual gaze, as well as in the mother’s words or sounds or physical touch that communicates her presence as a source of warmth, nourishment and love.

The presence of the mother becomes part of the infant’s internal world, like an emotional icon in the mind, imbued with feeling and significance5. The same is true of a father, or of anybody else who is close to the child as the child grows up. Even in adulthood, as we continue to meet new people, they too can become part of our inner world.

And even after these individuals are no longer an active part of our lives, their emotional icons can remain with us in the form of deep-rooted cognitive structures that influence how we think about ourselves and the world. Our values, our viewpoints, our very perception of what is “true” and what is not, is powerfully shaped by the people who have stirred our strongest emotions and desires.

What we take to be true about the world, then, doesn’t only exist as an abstraction or concept, but within other significant human beings in our lives. Truth is socially embodied.

More than that, when our relationships with others are stable and loving, then they—and the inner cognitive structures they leave us with—confer stability to our minds. Our ability to regulate our emotions, to focus our attention, to think deeply, to navigate conflicts and uncertainties in daily life—all this depends, in part, on our closest relationships.

And when these relationships suffer, we feel the impact on those deep mental structures, like the twisting or breaking of a scaffold. The impact isn’t only painful but can skew our perceptions of the world and our ability to function in a stable way.

Digital technology can also destabilize us. Part of the problem is that online relationships are not as complex or tangible as real ones (and in some cases are only simulations). The “people” we experience and internalize through social media are not fully real, and therefore are less likely to provide a durable inner structure—one durable enough to cope with reality.

For simulation not only demands immersion but creates a self that prefers simulation. Simulation offers relationships simpler than real life can provide. We become accustomed to the reductions and betrayals that prepare us for the life with the robotic…we have to be concerned that the simplification and reduction of relationship is no longer something we complain about. It may become what we expect, even desire.

from Alone Together by Sherry Turkle

There is another problem as well. Excessive participation in online social media means that we spend less time in real relationships, leaving us less deeply connected with actual human beings, and therefore less able to benefit from the stabilizing impact that such connections might otherwise provide.

Arguably, then, the impact of digital devices is a double blow—a matter not only of where they take us to—online relationships and simulations—but what they take us away from—tangible human beings. The result can leave us caught between unreality and estrangement. Our inner cognitive structures—the emotional icons in our minds—which should have given us truth and stability are, instead, faded and distorted. We end up more uncertain about what to believe and who we are, more susceptible to emotional and even mental health struggles, and—at a society-wide level—more prone to division and conflict.

This is our world.

Guidepost 2: Remove

Electrons are tiny particles that circle around the nucleus of an atom, and each electron has a “spin” that gives it a tiny magnetic force. Under normal circumstances electrons spin in random directions and their individual magnetic forces cancel each other out. But when a more powerful magnetic force is applied to a group of electrons, they all stop spinning randomly, and instead start spinning in the same direction.

This is one way of thinking about how digital devices have affected us collectively. Our devices are like giant magnets, scattered throughout society. Try as we might, our tiny individual magnetic forces are too weak to resist the pull, and we all start spinning in the same direction.

For this reason, efforts at using willpower to control our device use often fail. The force that we’re up against is simply too strong. And the more that devices become present in society, the harder it will become to resist their pull through individual effort and to reclaim the freedom to “spin” in our own unique ways.

This doesn’t mean there’s no role for digital minimalism in our lives. The more discipline we have around technology use, the better. But the likelihood of failure is high if that’s all we do. Our individual electron spin is too weak, and the force of the giant magnets is too great.

For practical suggestions on how to reshape your home environment to be more “human-friendly” see:

Beyond Digital Detox: How to Make a Home for Humans

Part of the solution is structural and social. It’s not enough that we limit our device use. We need to eliminate the presence of devices from certain situations and encourage a moral awareness that makes this a reasonable demand. Only a few decades ago, you could have visited a friend’s house and lit up a cigarette with children present, and possibly nobody would have cared—while today it would be a scandal. But to suggest that people don’t bring their phones into your home, or use them in front of your children, would itself be a scandal in most homes today.

And yet, this sort of suggestion isn’t as scandalous as it sounds.

has made a strong case for phone-free schools. The Institute for Family Studies has offered a series of guidelines to protect youth from the negative impact of devices and social media, including: prohibiting a social media company or website from offering any account, subscription service, or contractual agreement to a minor under 18 years old, without parental consent; mandating age-verification laws, to prevent access to social media or porn sites until a specified age; and giving parents the power to sue Big Tech for damages for the exposure of their children to dangerous material.Here are some further examples:

Phone-free schools have been enacted and proven effective in France, the State of Victoria in Australia as well as some school districts in Missouri, Pennsylvania, Maine, and New York.

Some college students are not merely discussing the impact of technology, but are taking action by spending an entire month living tech-free.

Our Lady Seat of Wisdom, a Catholic private university in northern Ontario, does not offer Wifi on campus, and thus encourages the formation of deepened relationships among its student body.

The L’Abri Fellowship in Switzerland adheres to tech guidelines because although technology is now considered “private”, it does “influence how we relate on a personal and on a community level”. Phones are to be kept on “Flight Mode” at all times and are not to be used during meals, lectures, discussions, etc.

Our homeschool co-op had a phone-free policy for both parents and students (for details see the Behind the Scenes section here)6.

Many of the initiatives above may seem unrealistic and wildly at odds with our default assumptions about technology use. Our first instinct might be, “Are you kidding? Do you seriously expect us to adopt these ideas for society as a whole?” And yet it’s only by taking these ideas seriously—by discussing, debating, and disseminating them—that we can start to question the current “normal” and begin a process that might move us toward a re-normalization of our values around technology.

We were promised a bicycle for the mind…We were not promised the disengagement and dullness of boring robots. We were not promised the addiction and anxiety of devices that tempt us with superpowers and leave us drained, that dangle hopes of satisfaction but leave us empty, that offer to recognize us but rob us of the face-to-face life for which we were made.

from The Life We’re Looking For by Andy Crouch

If we can remove or radically reduce digital technologies in the places where they shouldn’t be, then their destabilizing impact on our minds and relationships should, with time, diminish.

At the same time, we need to be realistic. In Reviving Ophelia, Mary Pipher describes the challenges that adolescent girls face:

[My daughter] and her friends were riding a roller coaster. Sometimes they were happy and interested in their world; other times they just seemed wrecked. They were hard on their families and each other. Particularly junior high school seemed like a crucible. Many confident, well-adjusted girls were transformed into sad and angry failures.

What’s remarkable about this passage isn’t about how it describes adolescent girls. If anything, it seems familiar, and could describe what happens to many girls who spend too much time on social media.

In fact, though, the passage comes from a book published in 1994, almost 30 years ago, long before anybody used digital technologies. Growing up has always been hard, in other words. And as anyone who has lived long enough knows, relationships at any age can be a challenge.

So, while the Remove recommendation is a fundamental step to improving our relationships, it won’t fix everything. It’ll only allow our electron selves to be freer, and more able to reorient to their local realities, whatever they may be.

Still, the more of that freedom we regain, the better we come to know each other as real people in real situations, and better at that complicated dance of “being together”, with all its power dynamics, shifting emotions, dueling viewpoints, personality differences, and most of all, the struggle to love and support one another within appropriate boundaries.

No human being can perceive the truth about another human being perfectly. But if we prioritize knowing each other in our relationships, this truth has a chance of growing, in that we can start to see each other not ideologically, or abstractly, or for profit or use, but closer to who we actually are.

We have invented inspiring and enhancing technologies, and yet we have allowed them to diminish us. The prospect of loving, or being loved by, a machine changes what love can be. We know that the young are tempted. They have been brought up to be. Those who have known lifetimes of love can surely offer them more.

from Alone Together by Sherry Turkle

Guidepost 3: Return

…a resistance fighter understands that technology must never be accepted as part of the natural order of things. - Neil Postman

Otherwise the war is over. -

adds.The present default around digital tech is something like, “anywhere, anything, anytime, for anyone”, whereas where we need to get to is, “only in certain places”, and “not everything”, and “it depends on your age”.

The more collective social conviction we have in making these changes, the more pressure it puts on Big Tech, government, and institutions, to implement new policies around tech use. In the meantime, we don’t have to wait, but can start implementing remove-type changes in our own lives and homes. This might feel difficult and strange at first, and it might take time to figure out what works and what doesn’t.

While the Remove step is a key part of the change, it is the Return to living within our human parameters, engaged in embodied reality and face-to-face relationships, that is the goal.

The image above illustrates that this return is not a single road, but includes a variety of possible paths starting with individuals committed to digital minimalism and extending to large-scale communities. This is not an exhaustive list, nor do we endorse one choice over another, but rather depicts various options that can move us in the right direction. Below you will find examples of individuals, families, and communities that reflect a deliberate effort to live rooted in reality.

Individuals

A dead thing can go with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.

G.K. Chesterton – The Everlasting Man

Several writers on Substack have been relating their experience of quitting (or trying to quit) social media and other digital addictions. You may find encouragement, resonance, and the needed “straw on the camel’s back” in these real-life parables. Stories can often deliver a better punch than a list of reasons to make this your moment to ditch your digital dependency and commit to cognitive liberty. Earlier this year, I gathered up as many of their stories I could find and published them in this post:

For more see:

- experiences travel without phone

- trades his phone for an axe

- leaves Instagram behind

- wakes up to life through unplugging on weekends

- relates his journey to digital minimalism

- aims to stay connected to physical reality

- provides practical guidance on his Substack Stay Grounded

Kaitlyn DeYoung writes especially for parents on Digital with Discernment

Families

The most extraordinary thing in the world is an ordinary man and an ordinary woman and their ordinary children.

G.K. Chesterton

The Benda family of Prague7 believed that “family is the bedrock of civilization, and must be nurtured and protected at all costs.” We fully agree.

Through their commitment to family, faith, relationship, and culture, the Bendas not only survived under an oppressive regime, but passed on their moral courage to their children, who continue to value and live out their parents’ convictions. They read to their children every night, using stories to help them learn the difference between truth and falsehood. They also organized frequent meetings, often centered around films8 (alternating between newer and older) that served as a focus for lively discussion and passing on of cultural information.

Recently, families have started to band together under The Postman Pledge, supporting each other in a resolve “to create a lower-tech environment for their families”.

wrote about her experience as part of a collective effort in Joining the Dance: Setting Aside the Screens to Build the City. writes in Mere Orthodoxy about a group of parents in her neighborhood who have also joined the pledge.Also see

’s blog Five Acres Four Generations, where she chronicles her family’s experience of living communally on a farm along with her parents and grandparents.Communities

…in a society of atomized individuals, as communist Czechoslovakia was, it was important for ordinary people to come together and to be reminded of one another’s existence. In a time when people have forgotten how to be neighbors, simply sharing a meal or a movie together is a political act.

from Live not by Lies by

There are a variety of flourishing communities that prioritize embodied relationships. The ones mentioned below are a mere sampling and we would love to hear from you if you have more examples to add (please let us and others know in the comment section!).

In an interview earlier this year with

, relates his thoughts on St. Jerome’s classical school community:I recently visited a lovely “Benedict option” style intentional Catholic community in Maryland, where more than a hundred families have sort of centered around the school (the St. Jerome Academy) there. I was very impressed, not just with what they’ve accomplished as a community, but by the general sense of goodness, humanity, and, well, sanity, that they’ve been able to build there, including for their children. I think these kinds of communities are likely to be a real bedrock of “resistance” moving forward; especially ones that can remain integrated yet distinct from broader society, without being totally isolated. By doing so they can serve as a “parallel polis,” providing not only community and solidarity for their members, but also serving as an example for others in society that a better life is possible.

When asked about specific examples of Benedict Option communities, Rod Dreher provided the following list:

a Catholic agrarian community around Our Lady of Clear Creek Abbey in eastern Oklahoma.

The lay community gathered around St. John Orthodox Cathedral in Eagle River, Alaska.

Trinity Presbyterian Church in Charlottesville, Virginia, which “is working towards incorporating a version of the Rule of St. Benedict within its congregational life.”

Rutba House, a New Monastic community in Durham, North Carolina, and its School for Conversion.

The Scuola G.K. Chesterton in San Benedetto del Tronto, Italy, is “run by Catholics for Catholic children, following the vision of the late Stratford Caldecott (see his essay, “A Question of Purpose”).”

The BenOpWeekend seeks to support people in building faith-centric communities.

provides a “practical handbook” with Building the Benedict OptionThis Benedictine Cohousing Community is based in the Monastery of St. Gertrude, in Cottonwood, Idaho, and “is pioneering a new way for women of all Christian denominations to live Benedictine, monastic life outside the traditional requirements of Roman Catholic religious life” (thanks to

for adding this suggestion).Bruderhof communities have settlements around the world including the U.S., U.K., Germany, Austria, Australia, Paraguay, and South Korea. You can read about their experiences at

.L’Abri, which was founded by Francis and Edith Schaeffer in Switzerland, also has locations around the globe and offers individuals “the opportunity to seek answers to honest questions about God and the significance of human life”.

So Let Us Begin

We desperately need to throw off the chains of solitude and find the freedom that awaits us in fellowship…Christians must act to build bonds of brotherhood not just with one another, across denominational and international lines, but also with people of goodwill belonging to other religions, and no religion at all.

from Live not by Lies by

More broadly, as mentioned earlier, I think a sort of revival is coming: a “second religiousness,” renaissance, or recommitment to inherited civilizational principles. History would strongly suggest something like this is now on the horizon. In fact I think it’s already happening, and I find that to be cause for hope. The only question is what direction this energy is going to take, and whether it will be strong enough to induce a more humane future—but that will be up to all of us to shape.

from an interview with

onWe started by asking where along the road of technology we took a wrong turn, and where we need to make a course correction. With the 3Rs of Umachining, what we have offered isn’t a comprehensive answer, but three guideposts that might help move us in the right direction: Recognize the damaging impact of technology wherever it happens, Remove it, and Return to one of the most essential things about human life—our embodied relationships.

Often, as we lament the state of our world, our instinct is to look to something in the past, whether some former stage of our civilization, or how we imagined people once were and might again become. While we’re sympathetic to this instinct, we’re not confident that this is the place to begin. For example, people can have quite different ideas about what aspect of our society we need to protect or restore—just spend enough time with a mixed group of religious people, or secular people, and that becomes clear.

Which means that if we start the course correction on the basis of a group-based “distinctive”, then we will find ourselves strengthened within our group, at the expense of becoming more disconnected from those who don’t share our distinctives.

We are not arguing for some kind of veiled ecumenism. Rather, what we are suggesting is that, in the shared struggle against the destructive side of technology, we need to give emphasis to what is foundational for all of us.

The first two signposts—Recognize and Remove—open the path of Return to that foundation, which is relationships. Many things apart from relationships matter in life, of course, but our view is that unless we prioritize our marriages, families, and the wider spheres of our human connections—unless we make this the alpha and omega of our efforts—nothing else will work—not religion, not philosophy, not nature, not even technocracy. It will all flounder, because it will either miss or misuse something more basic than all of these things: we are embodied relational creatures who thrive only when we are known and loved.

To take the contrary position, that we should accept a life of increasing digital disembodiment and simulated or simplified digital relationships—as if other-centered love could fully flow through a screen or retinal projection—as if the deepest needs of the human heart could be filtered through Big Tech’s corporate ambitions—is to risk distorting an essential part of what makes us human.

As followers of the Christian faith, we believe that other-centered relationships of love express the very nature of God, and the Great Commandment of the historic faith. And yet, we’re not making a theological argument. Even for those of a different religion or no religion, the premise of hope that we have suggested is—at a purely human level—graspable. We all know what sacrificial love means. Every infant knows it in a mother’s cradling arms; every elderly parent knows it in a child’s embrace. And even if our lives, by some misfortune or circumstance, have been so hard that we don’t know it, or have forgotten it, the proof is in the pain of its glaring absence.

The turn on the road is not a turn backward, but away from the virtual and toward each other.

We want to hear from you! Please share your comments, reflections, examples, and questions below.

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), consider supporting our work by becoming a paid subscriber, share this post, or simply show your appreciation with a ‘like’.

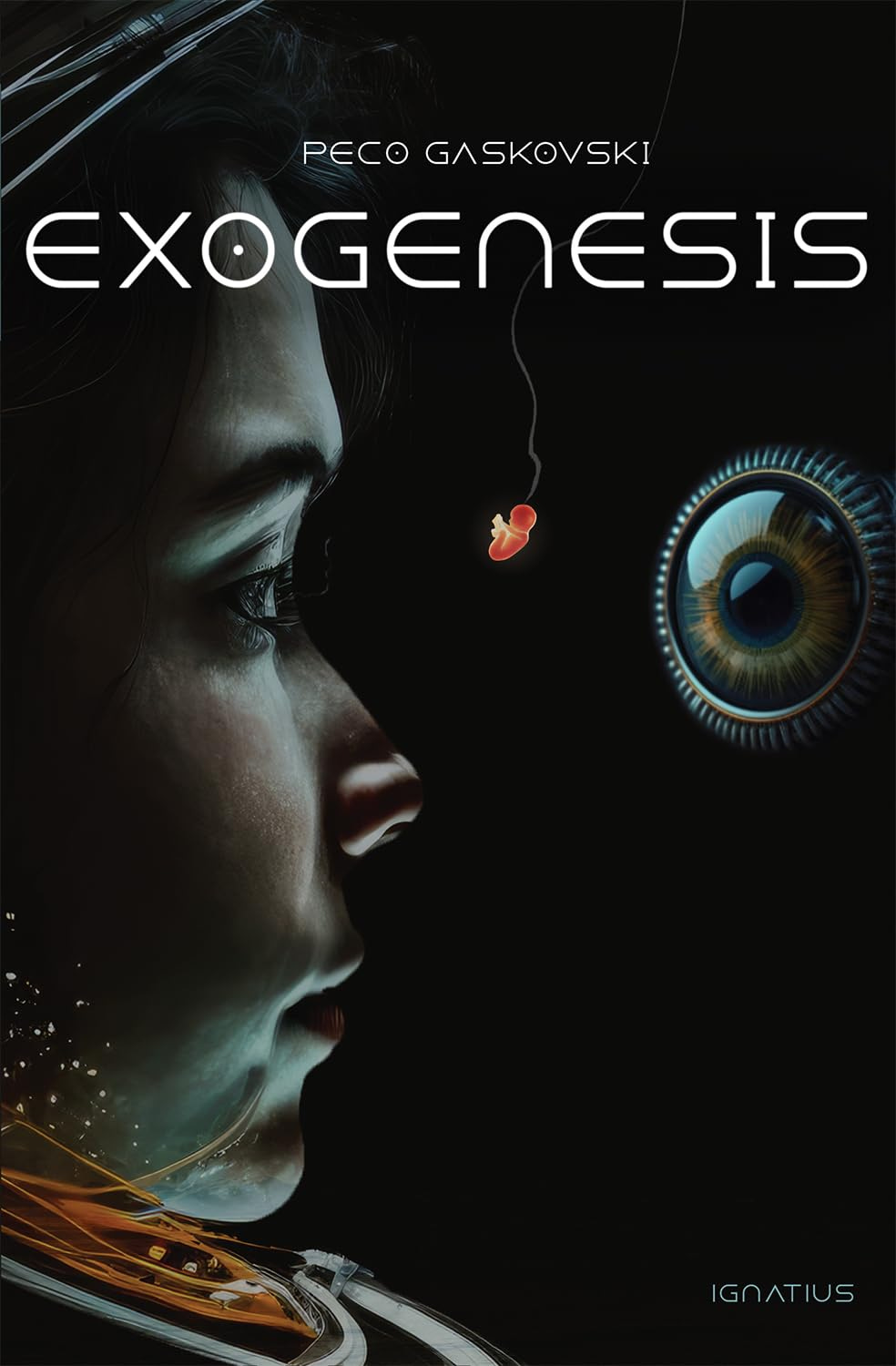

You can also support us by buying Peco’s new release Exogenesis (Ignatius Press), a novel which cuts to the core of what it means to be human in an increasingly technological world. Exogenesis imagines a technological future where a parallel rural society has arisen beside a technologically advanced city, giving it the feel aptly described by one reviewer of Blade Runner meeting The Benedict Option.

For a more comprehensive list of social and mental harms caused by social media and digital device use, consult the Ledger of Harms by Tristan Harris’ Center of Humane Technology and

’s Substack After Babel.A phrase used by Tristan Harris in his address to the Senate Commerce Committee.

See Kaitlyn de Young’s most recent post on Digital with Discernment about Snapchat’s manipulative “Friend Solar System” app.

Our daughter designed this logo during her time at the Classical Homeschool Co-op, which she sported on her book bag and t-shirt.

Another important element in the conversation I have with my kids includes discussing where these phones come from and where e-waste goes to. A book 'Cobalt Red' looks into the horrific slavery and exploitation that brings us just this one essential rare earth metal. In one passage the author describes the sun going down on a mine and the exhausted workers who mostly have never even seen a cell phone trudging home, and then contrasts with, in North America the sun is just now coming up and many people are reaching for their phones in a world where increasingly they believe that it is not possible to live without one.

I'm not doing justice to this powerful passage, but anyway, the horrors that bring us the ability to afford this technology would disturb us if we knew more about them. The fact is, it is very silly to think that we cannot live without them. We are participating in a temporary delusion of a minority of very rich folks when we accept this as a fact.

Clara

I am so happy to see the elements of "unmachining" laid out like this. I think many (most?) people have achieved some level of "Recognize" but don't know how to proceed to "Remove" and "Return."

One thing worth considering, however, is that I don't think you can fully Recognize the actual extent of how tech changes us until you at least get into the Remove stage, and maybe even more into the Return stage. Hence my essay to which you link (thank you!): I thought I knew well how bad constant internet was for me and my family but I actually had no idea of the extent to which it prevented me from experiencing my authentic self.

So those programs or experiments that get people on board for a specific practice or for unplugging for a length of time are more important than they might be if it were relatively easy to come to these conclusions on your own. They will get people to the space where they *can* Recognize fully.

It's kind of like when someone is in a clinical depression. The depression itself prevents that person from recognizing what they need to do to get help and getting them to act upon it. Depression delights ol' Screwtape because he can use it to tell people they aren't really depressed, everybody else is just the problem.

So with phones: the shallowness, emptiness, and distraction we experience keeps us from realizing that our healthy norm is actually *far different* from this, and we need to take action to get back there. We think instead that we are doing fine because we can manage to put the phone away for dinnertime.