The Inklings are not dead

Tolkien and Lewis might be gone, but there are still refuges of lifegiving creativity in the world

But we first have to recognize that we have been drugged—yes, we believers, no less than unbelievers. If we hope for a true new renaissance of faith and culture, we will have to first of all deal with our addiction to mediocrity, and at the same time keep our eyes open for those creative buds of new life that rise up, against all odds, in the midst of the soul-killing tsunami of contemporary culture.

– Michael O’Brien, interview

Prologue

I wish I could have spent an evening over supper with J.R.R. Tolkien or C.S. Lewis. There aren’t many writers today who are Christians and capable of producing an entire body of fiction that is maturely grounded in their faith, yet can reach people beyond their faith. Michael O’Brien is one such writer—the author of 15 novels and 30 books overall, in 14 language translations, and a prolific iconographer and painter as well.

Ruth and I first met Michael O’Brien through his novel Father Elijah. The book was given to us many years ago, when our lives had just emerged from a long night of spiritual darkness. It’s a discernibly Catholic story, yet it resonated with us so powerfully that, even though we weren’t Catholics, we hoped we might one day meet the author himself, and thank him for shining a light into our lives through fiction.

Then the coincidences began.

Jump ahead a few years. We made friends with a Catholic couple who later moved far away, and who by chance ended up living just down the road from O’Brien. A few years later, through the same friends, we got to meet O’Brien in his garden—a man of tall stature who exuded warmth and humility—and he gave me some encouragement in my writing that I’ve kept close ever since. Jump another three or four years, and I ended up publishing my own debut novel, Exogenesis, which by chance ended up right next to O’Brien’s Father Elijah in the alphabetical listing of Ignatius Press novel titles.

So, almost two decades after we met Michael O’Brien through his novel, things seemed to have come full circle (we did mail him a copy of my book—he liked it, thank goodness).

Now I’m a natural skeptic. I don’t like to make much of coincidences. Yet our need to connect things, to make sense of patterns in the world, reveals something basic about human beings. We aren’t just creatures of logic, but of imagination.

Imagination was the theme of a conference where we met O’Brien in person for the second time a few weeks ago—him and a motley cast of other writers and thinkers. None of us will ever have a chance to hang out with J.R.R. Tolkien or C.S. Lewis, but if our experiences at the conference showed us anything, it’s that there are still people of big faith in the world who are striving to revive our culture through the creative power of story.

The hobbit house

North of us is a town where billion-year-old granite breaks through the surface of the earth. The town is small, about a thousand people, surrounded by dense forests inhabited by bears and wolves and moose, and in every direction are hundreds of freshwater lakes which, if you saw them from the sky, would look like the fragments of a shattered mirror. It is a place of harsh winters, and a place where loons call out hauntingly on summer evenings.

A few weeks ago you might have glimpsed us in that town, if you had passed on the sidewalk one night and glanced through the front windows of a certain cozy dwelling. The interior was dim, lamplit, with two quaint rooms separated by a carved wooden archway. We might have been in Bilbo Baggins’ parlor, a gathering of dwarves before an adventure.

There were nine or ten of us around a dark wooden table, which was set with a modest supply of homemade wine and real Scotch, and (all of us quite sober) we talked about the raising of children and the demise of culture, and more obscure subjects, like McGilchrist’s ideas about the brain and Charles Dickens’ vision of the Virgin Mary. When we’d had our fill of the deep matters of life, we moved to the adjoining room, where the chairs were more comfortable. Here, our host and his friend played on the guitar and piano and fiddle, a range of folksy tunes from the ballad of Scarborough Fair to Johnny Cash’s Folsom Prison Blues, while the rest of us sang along, clapped, or step-danced—or if you are a natural introvert like me, just tapped your hand on the armrest of a leather chair.

What was it that made that evening such a delight? The music and deep conversation? A few sips of wine? Our delight included all of these things, but it was wrapped in a togetherness that was larger than everything else.

We had also spent most of the day at a conference on Literature and the Catholic Imagination at Our Lady Seat of Wisdom College. Not all of us were Catholic—I am Orthodox, while Ruth hails from a Protestant background—but we were all thinkers and writers of various sorts, and all belonged to a broad tradition of thought which was, at one time, the foundation of the West, the granite upon which the continent of our civilization was built.

Twelve hours earlier

Twelve hours earlier I was in a lecture hall at the College with about thirty people taking notes on a talk by Michael O’Brien. Catholic Fiction in an Age of Unbelief was the subject, yet O’Brien’s lecture pointed to universal truths that go beyond fiction, and beyond religion in the narrow sense.

In the early 1960s O’Brien, then a young teen, lived in the Arctic for three years. He also went through an agonizing time in the Canadian residential school system. The schools were administered by various churches, and its pupils were indigenous children who had been separated from their parents with the goal of assimilating them into Canadian culture. O’Brien himself wasn’t indigenous, yet during the 10 months of the year he was separated from family, he endured experiences that, in hindsight, are now sadly predictable: removing kids from their families, and putting them under the control of unsupervised institutional managers, places them at high risk of becoming the targets of predators—and if not that, then of being manipulated by the agendas of social engineers.

Not everything about O’Brien’s time in the Arctic was negative. He was surrounded by the beauty of the vast frozen North, and most of his friends were Inuit who lived simple, traditional lives. A few years later, when O’Brien’s family left the Arctic and moved back to the big city, the change for him and for his brother was “bewildering and disorienting” according to his biography:

[They] struggled with loneliness and a sense of existential emptiness. The life on the edge of civilization, with its experiences of nature and a low level of technology, had deeply affected them. Michael had worn moccasins and fur boots for so long in the North that shoes and rubber boots were now uncomfortable; he had not used a telephone or got into a bus for several years and thus felt intensely the increasing speed and noise of the modern world.

Remember, this was 1964, long before smartphones and social media put us all in a faint mental daze. The Machine isn’t a new thing, but an evolving thing.

O’Brien’s earlier experiences weren’t the only formative ones—his Catholic faith was a great consolation during his time at the residential school and throughout his life. But his early life experiences, both the beauty and the suffering, may have helped to infuse his art and thinking with a spirit that can speak to any heart.

Culture, consciousness, and humility

During the talk that morning at the College, O’Brien observed that,

culture does not merely passively reflect us, it powerfully influences us. It shapes and reshapes our perceptions, our consciousness, and hence our conscience, and thus our choices in the realm of action.

So many of us, myself included, often lapse into an automatic way of living. We aren’t always aware that we’re being influenced by the forces of culture—forces which are all around us, almost in the very air we breathe, like particulate matter spewing out of mufflers in a traffic-congested city. We constantly inhale these cultural particles, which float out of advertising, film, media, and the whole smoggy social and political atmosphere of our times.

One of the consequences is that we tend to accept Machine assumptions about life, including the idea, as O’Brien puts it, that materialism is “the whole truth about man”. If we are only material beings, then we can be reduced to biological creatures, social creatures, self-deifying creatures, possessed by the drive to become our own gods. O’Brien warns that “we must never forget that the inevitable outcome of the denial of, or rebellion against, the Creator of man is the negation of man”.

Another way of saying this is that we cannot function in a healthy way unless we understand how we, as finite beings, fit in relationship with the infinite Reality that gives life to us.

Our natural tendency is toward self-aggrandizement. Our egos convince us that if we aren’t big and important, then we are irrelevant. But if we follow our egos down the path of self-aggrandizement, our instinct will be to dominate other people, and to dominate nature.

If we are Christians, we look to God as the only counterweight great enough to offset the self-serving impulses of the ego. If we are not Christians, then what is our counterweight? It might be the love of our children; it might be some other purpose that serves the good, the beautiful, and the true. It’s a question nobody can really answer for us, yet one that burns in the back of our minds, though it can be disguised in uncertainty and despair: What is the point of it all? Why love anyone when I might not get anything in return? Why sacrifice myself? Why keep trying to wrestle back my own selfishness?

Even religious people can be overwhelmed by doubts and feelings of powerlessness. But it’s exactly here, O’Brien suggests, that we find the thing we most need: humility. The voice in our head will keep insisting we must be bigger, more dominant, more in control, to be anything meaningful in this world, when instead we need to become smaller in order to discover our real nature:

Humility would have us rejoice in our powerlessness, for in it we may find again our simplicity and thereby discover our true greatness—that is, as the children of God. And then we will see the proper proportion: We will know that we are damaged but not destroyed. We will learn that within us is a capacity for truth and for love, and a potential for forms of creativity that are practically infinite.

Humility is at the heart of Michael O’Brien’s own development as an artist. Back in 1971, during his first official showing at the Robertson art gallery in Ottawa, he sold 10 of 36 pieces, which the gallery owner said was “almost unheard of” for a first showing. The young O’Brien was overwhelmed by the positive response, yet his commitment to his faith led him to an unusual decision. From his diary entry:

I’m resolved to avoid involvement in “society circles”, and they were there last night [at the gallery] and most friendly. I don’t deny that for the most part, these “important” people are fine and good, but I am afraid of what being absorbed into their perspective in the culture would do to me.

Poverty must be my mistress, as St. Francis said. Constant work and interior search for light. –To grow in it and give what I can. Reputation, relevancy (social), entertainment, are things which mustn’t influence my work. The thing is to work on steadfastly as I have been.

How many artists, if offered a chance at worldly success, would instead choose the way of poverty and humility?

And poverty did come. During the conference talk, O’Brien recalled how there was a gap of 19 years between the writing of his first novel and the publication of his first book in 1996. When Ignatius Press, his eventual publisher, asked to see his manuscript, O’Brien declined. When they pressed him to send it, he explained that it would cost him $10 to mail the manuscript to San Francisco, and he was so poor he couldn’t afford the money.

The manuscript that he finally sent was Father Elijah, which remains one of his best-selling novels.

What do we imagine?

Later that day at the conference, I was in the same room at the same desk, listening to another speaker. Strangely, this speaker paused at the start of her talk, and then began to sing, “Imagine there’s no heaven—” Then she abruptly stopped, nodded at everybody, and instantly we erupted in unison:

It’s easy if you try

No hell below us

Above us, only sky

Imagine all the people

Living for todayImagine there's no countries

It isn't hard to do

Nothing to kill or die for

And no religion, too…

Some have called John Lennon’s Imagine an anthem of peace. Others have called it an ode to Communism. I might call it a secular sermon disguised as a pop lullaby. Either way, the odd thing is that we, an audience of devout Catholics, plus one Orthodox, seemed to know the words of Lennon’s ditty as instinctively as the Nicene Creed. Music, like literature, can powerfully shape our imagination, whether we want it to or not.

Yet Michael O’Brien reminds us that in the best of our literature,

the mind and heart are expanded as the reader apprehends dimensions of his inner life that so often lie dormant in a horizontally compressed society dominated by materialism, by utilitarianism, moral relativism, and a host of other tragically stunted concepts of what it means to be human.

And beneath all that there’s a more profound thing going on:

Directly, or by implication, [literature] asks: Do we live in a deterministic universe tyrannized by fate? Or do we live in a providential universe? And if it is a providential universe, how should the writer portray the interaction of grace and human freedom, which is, I believe, the real historical dialectic—the war between good and evil in all its fathomless complexity?

Great stories are often filled with surprise, especially moral surprise. The good man does an evil thing, or the evil man does a good thing (or else a really perverse or sickening thing) and we keep flipping pages to find out the next surprise. But if this is all that a story does, it functions as a literary drug. It stimulates us but doesn’t go any further.

Once, in the fantasy section of a used bookstore, I chatted with a fellow fantasy reader who told me that he found Game of Thrones difficult to read (or to watch), as there was so much violence and rape, and so many of the “good” characters die. “But of course that’s realistic,” he said with a shrug. “That’s how our own medieval world really was.”

Good people do die, in books and in life. But the question we face, according to Michael O’Brien, is whether a person’s death is meaningless, because the universe itself is meaningless—in which case we really are “tyrannized by fate”—by cruelties and misfortunes that arise by chance—or whether there is any universal grace that redeems death and suffering.

It’s hard to write redemptive stories. They can feel artificial and forced. But it’s been done many times and in diverse ways. We see it in The Lord of the Rings, which J.R.R. Tolkien himself called “a fundamentally religious and Catholic work; unconsciously so at first, but consciously in the revision”. And if you think Tolkien’s fantasy is morally simplistic, then you can find it in Flannery O’Connor’s Wise Blood, a more realistic (and darkly comical) novel filled with a lot of morally messed-up people, yet which somehow, miraculously, ends with repentance.

The night women of Paris

Not all of us are writers, yet we are all, in part, authors of our lives. Every choice we make is shaped by the beliefs we accept or reject. Do we live in a deterministic universe, or a universe animated by grace? Does our imagination deform us or does it deepen our humility, faithfulness, patience, and love? Does our imagination glamorize evil, making it more attractive and desirable than the good?

That last question is a tricky one. Many books (and films) can turn us into voyeurs: we observe the moral degradation in other people’s lives with addictive fascination. It’s tempting to do as a writer; it’s hard to resist as a reader.

At the end of O’Brien’s talk, I put up my hand and asked how he managed the problem of depicting evil. He told the story of a French painter who often took as his subject matter the prostitutes of Paris. Later, when this painter returned to his Catholic faith and started going to church, he asked his confessor, “Should I stop painting these women? Is it sinful to paint prostitutes?”

His confessor told him that he should not stop painting them. But he should look at these women in a new way. In each of them he should see his own sister, his own mother, his own daughter.

If love is at the center of those who follow Christ, then it means we strive to see the face of Christ in everyone. Truly I tell you, whatever you did for one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did for me.

Accelerating change and the threat of societal disintegration has left many of us unsettled, and confused about what to make of the world we live in. But hope is not lost. There are still voices we can trust. There are still writers and artists like Michael O’Brien who, in the spirit of Tolkien and Lewis, are working to revive our culture through the power of story and a grace-filled imagination.

That night at the hobbit home, in a town on the edge of the wilderness, those nine or ten who had gathered for an evening of conversation and song experienced a sense of togetherness; but this togetherness was embedded in a shared vision of reality. It’s not that we saw things exactly the same way. We were divided by different personalities and life experiences, and by old church schisms. Yet the lines of separation between us seemed small, very small, as if they were no more than a trickling stream.

The world is changing fast, but there are still refuges of lifegiving creativity. Tolkien and Lewis might be gone, but the Inklings are not dead.

Many thanks to Michael O’Brien for providing us with the manuscript of his talk and a selection of his artwork to share with you.

Links, books, and more

Michael O’Brien’s full talk at the conference can be downloaded here.

Are you a writer? I encourage you to read O’Brien’s Open Letter to Fellow Artists and Writers , which I have kept next to my writing desk ever since I first discovered it.

Our Lady Seat of Wisdom College has a fascinating founding history which you can read about here. It is a perfect example of a “Benedict-Option” style intentional community that we discussed in The 3Rs of Unmachining. The college

is one of 28 global Catholic higher education programs recognized for excellence in faithful Catholic education in The Newman Guide.

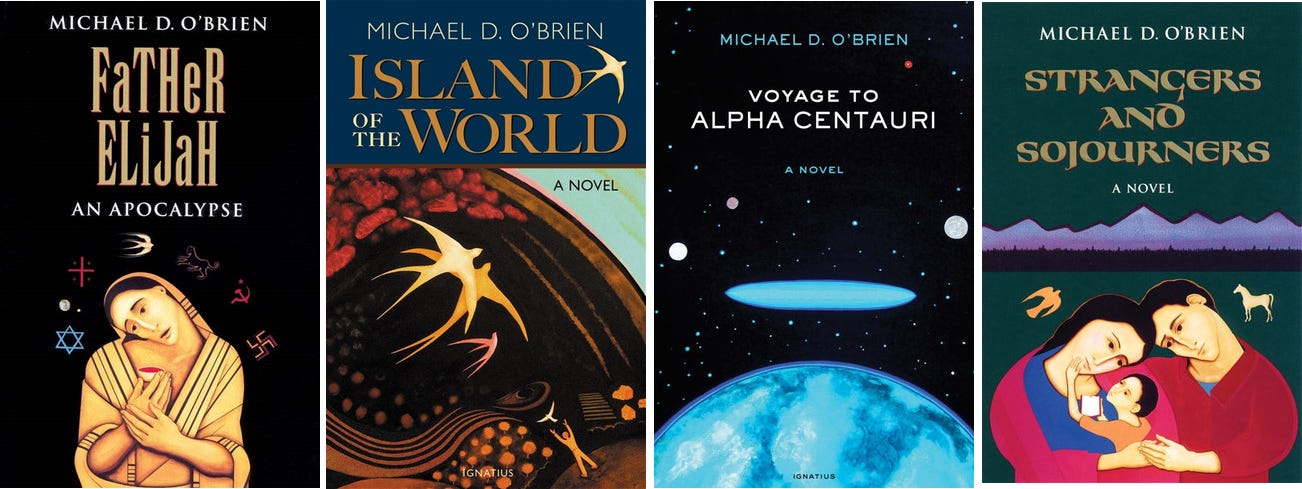

If you would like to delve into O’Brien’s novels, here are some of our favorites: Father Elijah, Island of the World, Voyage to Alpha Centauri, Strangers and Sojourners. You can find all his novels at Ignatius Press here or at your preferred bookseller.

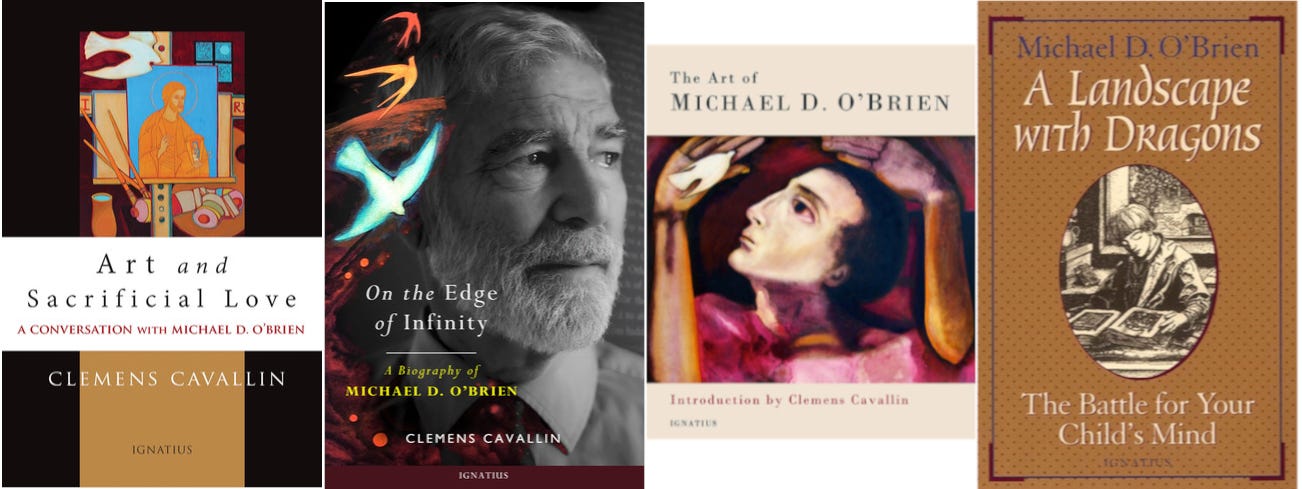

His non-fiction books include, The Art of Michael D. O'Brien, and A Landscape with Dragons - The Battle for Your Child’s Mind. Clemens Cavallin is the author of O’Brien’s biography, On the Edge of Infinity, as well as a conversation on Art and Sacrifical Love.

Would you like to join us on a pilgrimage in Spain? Join me, my wife

, and on the Camino de Santiago pilgrimage in Spain in June 2025. Space is limited and filling up. We would love to have you along! See here for details.

Please share your thoughts, reflections, and questions in the comments below.

We would love to hear from you!