The Flavors of Faux History: Preparing for the Collapse of Knowledge

Blancmange, AI tofu, ideological MSG, and booklegging for history

For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, we have converted the post into an easily printable pdf file.

A great civilization is not conquered from without until it has destroyed itself from within.

Will and Ariel Durant

When I (Peco) was eleven, a friend of mine showed me a staff he’d carved from a piece of wood with a whittling knife. On the staff were strange markings, which he called “runes”, a type of writing from a place called “Middle-earth”. I’d never heard of Middle-earth, and as I stood there, handling that staff like a magic artifact, my friend told me astonishing stories about hobbits, dwarves, and the Misty Mountains.

I came away feeling that Middle-earth might have actually existed.

How could I know for sure?

When I got home, I consulted the most trusted source of knowledge in my possession: an orange hardcover set of encyclopedias. From these sage volumes I had learned of the ancient Egyptians and the Roman Empire, and many other subjects, yet as I searched the index and flipped the pages, there was no reference to Middle-earth, the Misty Mountains, the Third Age, or anything else my friend mentioned.

I was crestfallen. Middle-earth was fantasy. I’d wanted it to be real, but it wasn’t.

I soon plunged into the works stories of J.R.R. Tolkien, which I now knew were fictional, yet I never got over the aching wish that Middle-earth should have been real.

Decades later, I still feel this way.

We all struggle with fantasy. We want life to be a certain way, and it can be hard to let go of the stories we tell ourselves about how life is or ought to be, even when the evidence starts to point us in a different direction.

Part of being a grounded human being is learning to distinguish between what is true and real versus what is untrue or fantasy.

Of course, this is not always straightforward.

Pilate once asked a Jewish rebel, “What is truth?”. We’re still asking that today. Sit down with a philosopher or Buddhist, and you can end up feeling as if nothing is certain. Sit down with a politician and you can end up feeling everything is certain.

As individuals we’ll never have perfect certainty about what stories about life are true or false, yet we need stories that are true enough and trustworthy enough—at least if we want to avoid being confused about our purpose and identity.

The same holds for a society. As a society we tell stories about our past—our history—to remember where we came from and what our values are. No history is absolutely certain, and probably shouldn’t be, yet some histories are better than others, more trustworthy than others.

A good history can give society a stable understanding of itself and its purpose, while a bad history can lead us into confusion and conflict.

Which is where we might be headed.

In today’s piece we explore why it’s harder than ever to know our history, and how we might prepare for the impending collapse of historical knowledge.

It is useful to remember that history is to the nation as memory is to the individual. As a person deprived of memory becomes disorientated and lost, not knowing where they have been or where they are going , so a nation denied a conception of the past will be disabled in dealing with its present and its future.

Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr.

The rise of blancmange history

There are different flavors of bad history, and the first bad flavor is blancmange1 history.

We know that Neil Armstrong landed on the moon in 1969, the Holocaust really happened, and Pliny the Younger survived the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in 79 A.D., while his uncle Pliny the Elder did not.

Or are those just my own “opinions”?

The digital age has made it easier for people to rewrite history, simply by looking for content that confirms their beliefs or else by creating that content. It’s like going to a restaurant in search of our favorite food, or else being the chef who makes the food. On the internet, words are cooked, ideas fried, stories boiled, pictures spiced, and the unpleasant bits are sliced off—and voilà! Something consumable comes out of the oven.

And often it’s passed off as knowledge.

This happens not just because people are trying to spread “fake news”. It happens because we all have an urge to make sense of our lives and the world. Digital content is an easy way to satisfy that urge, but that same content is also easy to manipulate, which means the search for knowledge can turn into a search for whatever satisfies us.

At worst, the “knowledge” we discover online can turn out to be more like blancmange pastry: a sweet mass that tastes good and goes down smoothly, a kind of high-sugar trans-fat information blob, without any real research or scholarship behind it. Blancmange knowledge doesn’t nourish us with much truth.

Blancmange history is a specific category of false or misleading information, in this case about the past. It might seem unthinkable that we should ever become confused about the past, given that we have qualified historians, history books, archaeologists, eyewitness accounts, documents, artifacts, entire university departments devoted to subject. But it will always be easier to google things, which means we’re always going to be vulnerable to the endless varieties of blancmange being served in the echo chambers of the internet, sweetened according to our preference.

And it can even be addictive.

Blancmange knowledge is part of a larger trend, in which we’re becoming disconnected from real and nourishing things, and instead consumed in what David Brooks has called the junkification of American life:

We have access to wonderful things. But they require effort, so we settle for the junky things that provide the quick dopamine hits. We could all be eating a Mediterranean diet, but instead it’s potato chips and cherry Coke. We could enjoy the richness of full awareness, but booze, weed and other drugs provide that quick reward. Think of all the things in American life that seem to offer that burst of stimulation but threaten to be addictive — gambling, porn, video games, checking email…

The result is we’re now in a culture in which we want worse things — the cheap hit over the long flourishing. You reach for immediate gratification, but it fails to satisfy…As the psychiatrist Anna Lembke writes in her book “Dopamine Nation,” “The paradox is that hedonism, the pursuit of pleasure for its own sake, leads to anhedonia, which is the inability to enjoy.”

In the case of blancmange knowledge, the paradox is that the digital world, which makes it more convenient to access information, is also making it more difficult to differentiate true knowledge from false knowledge. The problem isn’t just that there’s so much knowledge out there, but that our motivation is driven by the pursuit of personal satisfaction rather than the pursuit of truth.

Meaning you don’t have to believe the Holocaust, if that comforts you, and you don’t have to believe that Neil Armstrong landed on the moon in 1969, if that satisfies.

The real danger of blancmange history is not that we are confused about truth, but that we cease to care about it.

AI and “tofu history”

Our second flavor of bad history is tofu history. It may sound bland (and in a way it is), but it’s an unhealthy kind of bland.

Knowledge can fade for many reasons, and ironically, the latest of these reasons may turn out to be artificial intelligence. Currently, 77% of our devices feature some form of artificial intelligence. Increasingly, we don’t just look things up on the internet, but ask AI to look things up for us. But our reliance on AI for knowledge might also result in “knowledge collapse”.

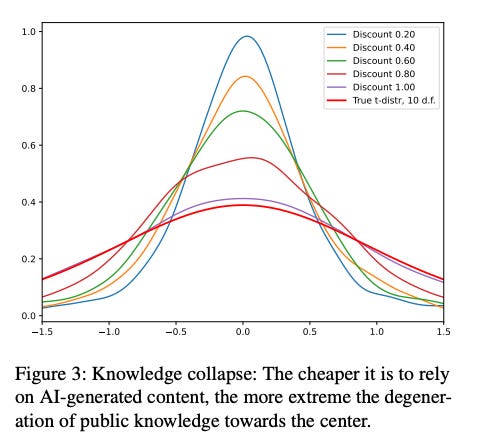

According to data scientist Andrew J. Peterson, the knowledge we get from AI can leave out original or unorthodox ideas, as AI outputs tend to focus on the “center” of the training data:

Over time, dependence on these [AI] systems, and the existence of multifaceted interactions among them, may create a “curse of recursion”…in which our access to the original diversity of human knowledge is increasingly mediated by a partial and increasingly narrow subset of views…[so that eventually] certain popular sources or beliefs which were common in the training data may come to be reinforced in the public mindset (and within the training data), while other “long-tail” ideas are neglected and eventually forgotten.

In the case of AI outputs about history, the result would be common and mainstream facts and interpretations about events of the past, rather than the full diversity of historical knowledge.

We might call this sort of knowledge “tofu knowledge”: common, conformist—and kind of bland.

History salted with ideological MSG

Remember Google’s AI model Gemini, which produced historically false pictures of Black Nazis and American Indian Vikings?

It’s a glaring example of how ideological bias enters into the design of AI. This type of bias is so absurd that even non-historians can see it.

But not every bias is that obvious.

Last year we attended a public talk on AI, where an expert told the story of how a certain artist tried to use AI to predict the future of art.

To make this prediction, the artist decided that the AI model should be trained on all the available art from the past. So, in the case of European art, this would include the art of the Greeks and Romans, and the Middle Ages, and the Renaissance, and so on, right up to the present. Sounds pretty reasonable, right?

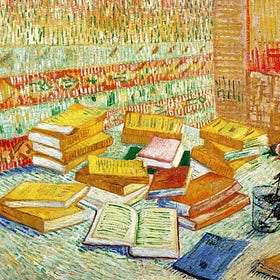

But the AI expert didn’t think so. She felt this type of AI model might result in a bias, as most artists in the past tended to be men and belonged to certain cultural backgrounds. Therefore, the expert proposed that only art from the last few decades should be used as training data—meaning no Rembrandt, no Monet, no da Vinci, no Van Gogh, no Michaelangelo.

In the expert’s view, using only the last few decades of art would result in less gender bias and less cultural bias. The expert seemed blissfully unaware that she had introduced a new source of bias that was, arguably, even more serious: the suppression of art history based on her own values.

AI is not neutral. It’s designed by individuals with beliefs, values, and worldviews that influence which data are used to train the AI, and which data are not used or are given less weighting.

To use a cooking metaphor, MSG (monosodium glutamate) enhances certain food flavors, but not others. The same can happen when AI is deliberately biased to tell a certain kind of history.

Every history contains bias, of course, but when the bias is too strong and calculated, it’s like adding too much MSG to bring out certain “flavors”. The result is a misleading understanding of the past—like Google’s Black Nazis and American Indian Vikings.

The MSG problem may become far worse in coming years.

A recent study published in the journal Science showed how AI chat bots can reduce people’s beliefs in conspiracy theories by an average of 20%. On the face of it, this sounds like a promising study with beneficial applications. Train AI chat bots in the facts and evidence, and then deploy these chat bots all over the Internet to help combat disinformation and steer people back toward “truth”.

But who trains the chat bots?

We are back to the original problem. Somebody has to give the AI model a set of data that says “this is conspiracy theory” and “this is fact-checked knowledge”. Surely experts will make this decision, but which experts? Are we talking about experts from the Republican Party, or experts from the Democratic Party? American experts or Chinese experts? Whose MSG are we adding to the story?

Chat bots that can be trained to speak truth can also be trained to say anything.

Get your own physical books—and don’t depend on public libraries

Blancmange history is flavored to satisfy our own preferences. MSG history is flavored to satisfy someone else’s preferences. Tofu history is flavored to satisfy conventional preferences. Nor are these problems entirely distinct. One person’s blancmange can become another person’s MSG.

Even before the digital age, history could be unreliable, biased, fabricated, manipulated. But the digital age has amplified these problems.

We’ve written previously about the importance of physical books as a vital alternative to digital content. Physical history books aren’t a perfect solution to the problems of historical bias and inaccuracy, but they do have one distinct advantage:

Books are stubbornly stable. Once the words are printed on the page, we can be certain that certain words will not mysteriously change or vanish because somebody in Silicon Valley has tapped a button to adjust the “overcompensation”, or that dates of important events will slide around depending on the changing moods of society.

And we need our own physical books. Public libraries are great, but we can’t depend on our libraries to save us. Many libraries are downsizing their print book collections in favor of digital books, yet digital books must be licensed, and that license is held by the corporations that sell the books—which means that knowledge may be increasingly under the management of corporations.

Some libraries have tried to avoid this difficulty by digitally scanning physical books that they already have in their collection, and then loaning out these digital copies. But a recent court decision in the US has ruled against this model. As one commentator observes:

This decision harms libraries. It locks them into an e-book ecosystem designed to extract as much money as possible while harvesting (and reselling) reader data en masse. It leaves local communities’ reading habits at the mercy of curatorial decisions made by four dominant publishing companies thousands of miles away. It steers Americans away from one of the few remaining bastions of privacy protection and funnels them into a surveillance ecosystem that, like Big Tech, becomes more dangerous with each passing data breach. And by increasing the price for access to knowledge, it puts up even more barriers between underserved communities and the American dream…It doesn’t stop there. This decision also renders the fair use doctrine—legally crucial in everything from parody to education to news reporting—almost unusable.

Booklegging for History

There is no better teacher than history in determining the future. There are answers worth billions of dollars in a $30 history book.

Charlie Munger

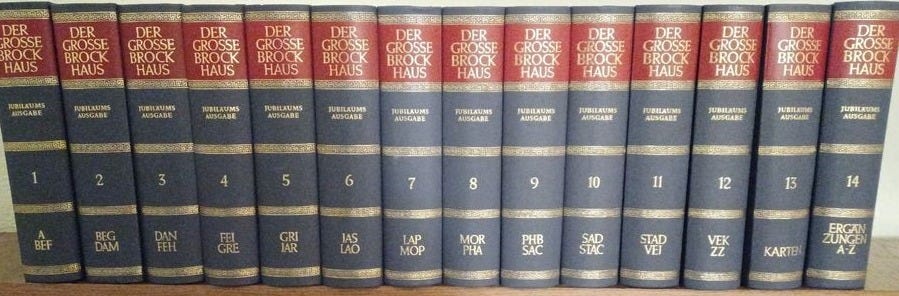

One of the first things on my (Ruth) late father’s agenda after he married my mother in 1971, was to purchase an entire encyclopedia set (22 volumes) at the cost of $113 Swiss Francs per issue. Calculating for inflation, this means he spent an estimated $8798 dollars. Although this type of expense would make any newlyweds shake in their financial boots, my father wanted to ensure that his future children would have access to knowledge. My mother concurred and still has this set in her living room bookcase.

My father’s emphasis on having knowledge accessible in physical books has evidently rubbed off on me. I started curating our own home’s collection more deliberately around fifteen years ago, when I noticed that local libraries were discarding entire sets of encyclopedias on medieval history, reference books, and classic biographies because people were not checking them out.

In our post earlier this year, A Guide to Booklegging: How (and why) to collect, preserve, and read the printed word, Peco and I recommended that, “we turn our homes into book monasteries, populated by silent monks who stand patiently on their shelves, waiting for us to commune with them. We can preserve and carry on the best of human society, one that will live on long after the floodwaters of digital dross fade away.”

For today’s post, we invited Substack writers and readers to contribute their recommendations for trustworthy books that tell the history of the West and the world more generally2.

Below the main recommendations we also include suggestions for high school students and younger readers.

Please note that we recommend these books as considerations, not as endorsements for everything they say. This is in no way an authoritative or exhaustive list and we are open to suggestions.

You’ll notice most of the recommendations involve Western history, but feel free to share any recommendations you might have for non-Western history, including Asian, African, and other major world histories.

We encourage you to add your own recommendations in the comments section.

Finally, we offer this post for free, because we want as many people as possible to benefit from these resources. It did however take an immense amount of time to create. If you find this post helpful (or hopeful), consider supporting our work with a paid subscription.

Many of the books listed can be found in used bookstores, can be ordered from your favorite book merchants, or in the “History” section in our Unconformed Bookshop. You can download an alphabetized list of the history book recommendations here:

Brown, Peter. The Rise of Western Christendom: Triumph and Diversity, A.D. 200-1000

and “for sheer fun”:

Norwich, Julius. The History of Byzantium Series

from has these suggestions to offer:Holland, Tom. Dominion: How the Christian Revolution Remade the World

Pegg, Mark Gregory. Beatrice’s Last Smile: A New History of the Middle Ages

Price, Simon and Peter Thonemann. The Birth of Classical Europe: A History from Troy to Augustine

Robertson, Ritchie. The Enlightenment: The Pursuit of Happiness, 1680-1790

Seidentop, Larry. Inventing the Individual: The Origins of Western Liberalism

Stark, Rodney. The Victory of Reason: How Christianity Led to Freedom, Capitalism, and Western Success

from finds this series “fantastic”:Oxford History of the United States Series by Oxford University Press

“After the Bible and the Greeks, I’ve found the “universal history” books of the medieval period to be fascinating in connecting the Western European nations to the rest of the “western story”.”Bible (Orthodox; Catholic; King James Version; NIV)

Of Monmouth, Geoffrey. The History of the Kings of Britain: An Edition and Translation of the de Gestis Britonum

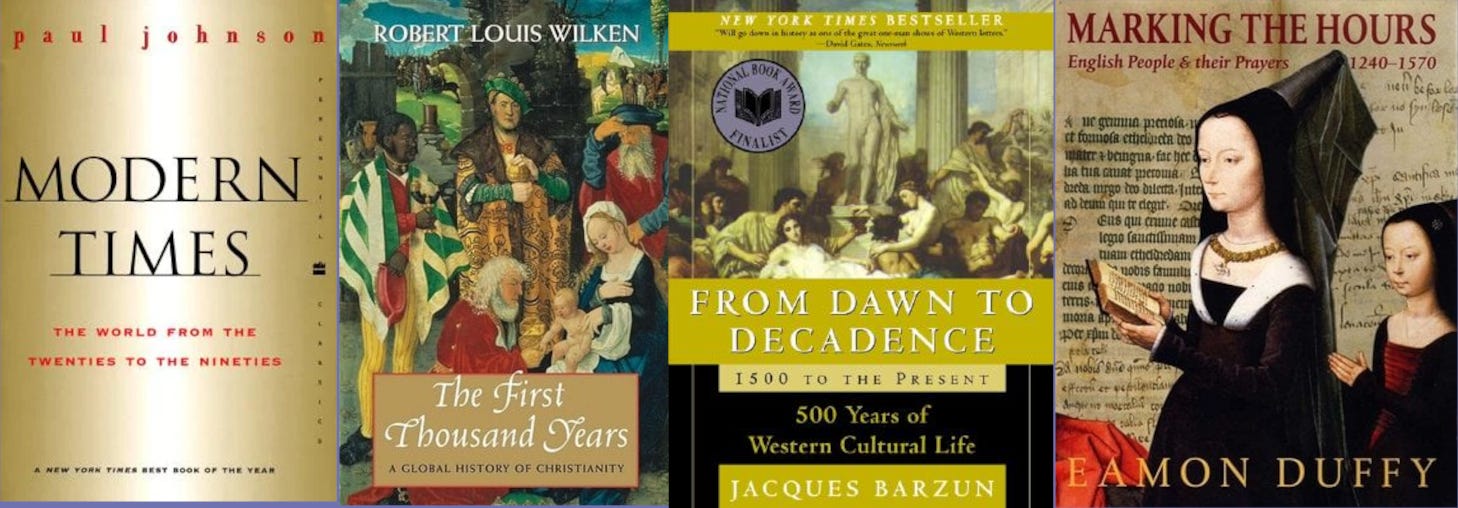

from suggests:Barzun, Jacques. From Dawn to Decadence. This one goes into very penetrating detail about the culture of the West from 1500 to the present day. It might fit more into the category you are looking for.

Johnson, Paul. The Birth of the Modern: World Society 1815-1830. Looks closely at a pivotal span of years. Reads like a giant rabbit trail but it is very entertaining and thought-provoking. It’s 1000 pages long, though.

Koestler, Arthur. The Sleepwalkers: A History of Man's Changing Vision of the Universe

Morison, Samuel Eliot. The European Discovery of America, Vol 1: The Northern Voyages, 500-1600 and The European Discovery of America, Vol 2: The Southern Voyages 1492-1616 . Morison was a sailor and he knows what he was talking about. A very good account of Magellan’s voyage around the world is included. Lots of very detailed maps and photos.

recommends:Johnson, Paul. The History of the American People

Strickland, John. The Age of Paradise: Christendom from Pentecost to the First Millennium and The Age of Utopia: Christendom from the Renaissance to the Russian Revolution

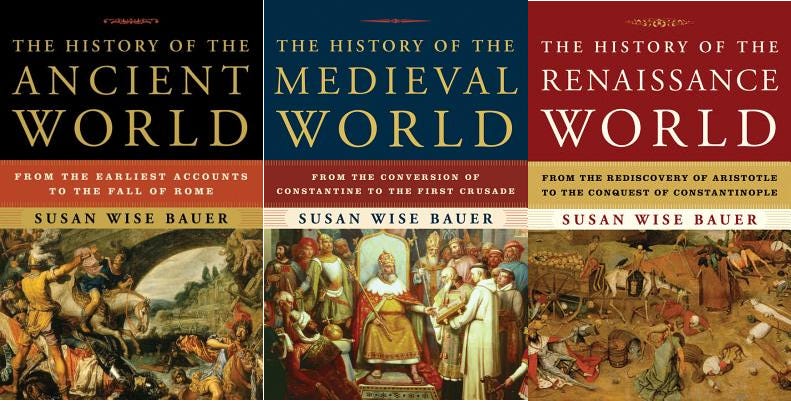

Wise Bauer, Susan. The History of the Ancient World, The History of the Medieval World, and The History of the Renaissance World

from recommends:Churchill, Winston. A History of the English-Speaking Peoples (three volumes)

Gilbert, Martin. History of the Twentieth Century

Gombrich, E. H. A Little History of the World

Plutarch. Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans (Complete and Unabridged)

Herodotus. The Landmark Herodotus: The Histories

and recommend:Taylor, Charles. A Secular Age

sums up his recommendations as “How we live together, how we live with ourselves and how we apprehend God.”Benedict of Nursia. Rule of St Benedict

Kempis, Thomas A. Imitation of Christ

Teresa of Avila. The Interior Castle

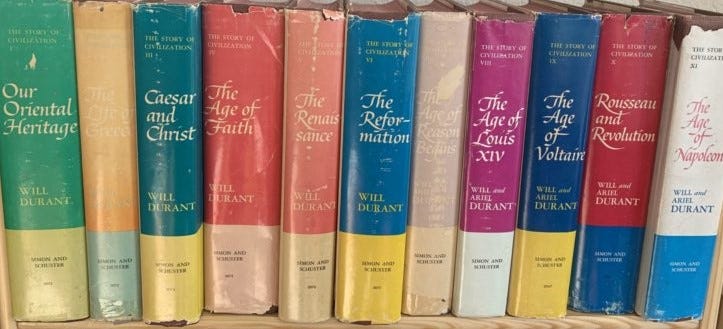

recommends:Durant, Will and Ariel. Story of Civilization series

from the recommends:Caroll, Anne. Christ the King Lord of History: A Catholic World History from Ancient to Modern Times

Caroll, Warren. The Rise and Fall of the Communist Revolution,

Johnson, Paul. Intellectuals: From Marx and Tolstoy to Sartre and Chomsky, Creators: From Chaucer and Durer to Picasso and Disney, and Modern Times: World from the Twenties to the Nineties

McCoullough, David. 1776, The Presidential Biographies: John Adams, Mornings on Horseback, and Truman, and Great Achievements in American History: The Great Bridge, the Path Between the Seas, and the Wright Brothers

from Art for the Liturgical Year recommends:Barzun, Jacques. From Dawn to Decadence - 1500 to the Present: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life

Clark, Kenneth. Civilisation

Duffy, Eaman. Stripping of the Altars and Marking the Hours: English People and their Prayers: 1240-1570

Gregory, Brad. The Unintended Reformation: How a Religious Revolution Secularized Society

Johnson, Paul. Modern Times: The World from the Twenties to the Nineties

Wilkin, Robert Louis. The First Thousand Years

recommends:Lord Acton. “The History of Freedom in Antiquity“ and “The History of Freedom in Christianity“ in Essays in the History of Liberty

McNeill, William H. The Rise of the West and The Pursuit of Power

Macfarlane, Alan. The Making of the Modern World

Scott, James C. Seeing Like a State:How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed

from suggests:Cochrane, Charles Norris. Christianity and Classical Culture: A Study of Thought and Action from Augustus to Augustine

Also,

recommends: Gombrich, Eh. The Story of ArtAsian, African, and other major world histories

Brown, Dee. Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee: An Indian History of the American West

Fairbank, John King and Merle Goldman. China: A New History

Holcombe, Charles. A History of East Asia: From the Origins of Civilization to the Twenty-First Century

Keay, John. India: A History

Lee, Ki-Baik. A New History of Korea

Marrin, Albert. America and Vietnam: The Elephant and the Tiger

Meyer, Milton W. Japan: A Concise History

Reader, John. Africa: A Biography of the Continent

Shillington, Kevin. History of Africa

also recommends:Boyce, James. Van Diemen’s Land

Fidler, Richard. Ghost Empire

Kapuściński, Ryszard. The Shadow of the Sun

For high school students and younger readers

I asked

from for her recommendations for high school students and here is what she had to share:In the classical humanities class I teach, I use Western Civilization: A Short History by Paul Waibel as our go-to spine.

I also like A History of the English-Speaking Peoples by Winston Churchill, First Principles by Thomas Ricks, anything by Roger Scruton or Russell Kirk, and Timeless by Steve Weidenkopf for a good broad overview of Church history.

Primary source documents are also key! Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville and Reflections on the Revolution in France by Edmund Burke are essentials and I have my students read excerpts from both.

I also have my students read letters from great thinkers of the west — Posterity by Dorie McCullough Lawson is a good resource; it's a book of letters from great Americans in history to their children (so, Rockefeller, Abigail Adams, Mark Twain, etc.).

As for recently written, I enjoyed

's book How to Save the West (he's on Substack) — it's a good resource that I plan to reread at some point.

For students from grade one to twelve, several readers have recommended the Ambleside Online Master Book list, which contains recommendations for history books. You can access the list directly in a document here:

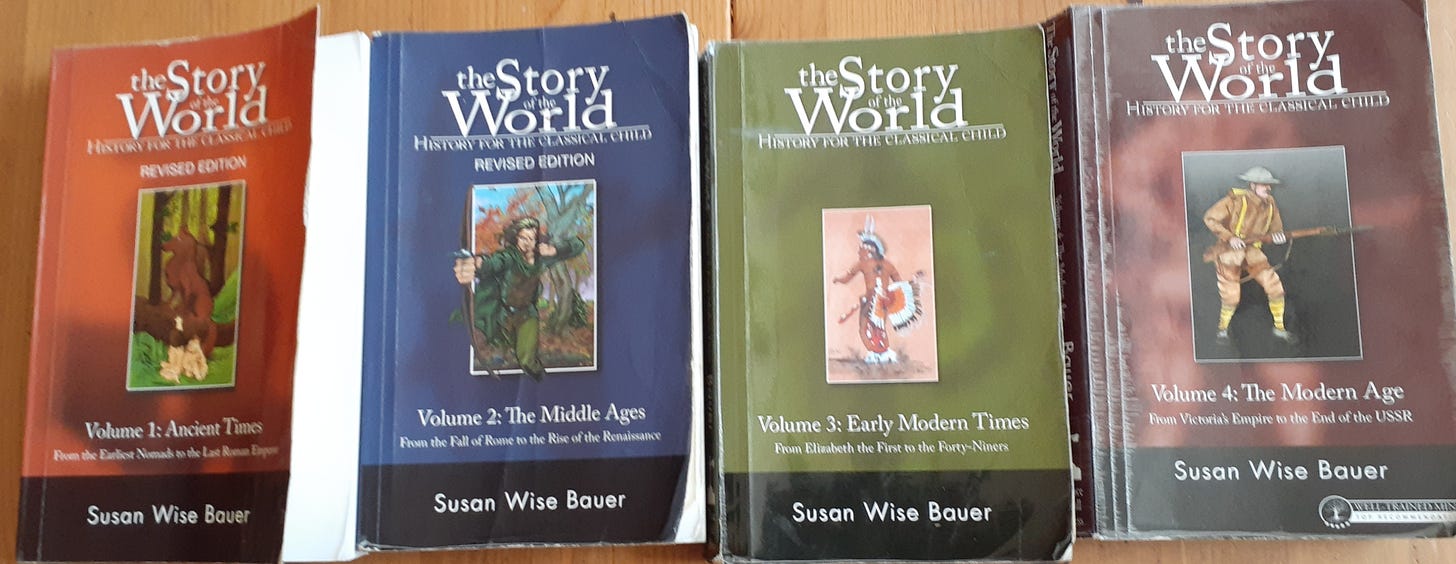

When our children were in elementary and middle school, we all greatly enjoyed the Story of the World series by Susan Wise Bauer. Each read-aloud volume comes with an accompanying activity guide (including map work, narration, and further reading) and can also be purchased in an audio version narrated by Jim Weiss.

Wise Bauer, Susan. The Story of the World: Ancient Times, The Story of the World: The Middle Ages, The Story of the World: Early Modern Times, and The Story of the World: The Modern Age

from recommends the following as historical accounts worth preserving:Chamber, Whittaker. Witness - The true story of Soviet spies in America and the trial that captivated a nation

Cheng, Nien. Life and Death in Shanghai

Gyatso, Palden. The Autobiography of a Tibetan Monk

recommends “primary sources all the way!” and offers a free directory of resources on . As a summary he does recommend:Spielvogel, Jackson J. Western Civilization

recommends:Marshall, H.E. Our Island Story: A History of Britain for Boys and Girls, from the Romans to Queen Victoria

to which I would also add:

Dickens, Charles. A Child’s History of England

suggests:Marshall, H.E. This Country of Ours: The Story of the United States

Dolnick, Edward. The Clockwork Universe: Isaac Newton, the Royal Society, and the Birth of the Modern World

adds:Morris Lester, Katherine. Great Pictures and their Stories (1927)

Also, some final general resources for young learners:

National Geographic Concise History of the World: An Illustrated Time Line

Hammond Historical World Atlas

Jackdaw Portfolios - contain facsimiles of primary documents, essays (Broadsheets), photos, annotations, transcripts, etc.

Please note: and I will host a live zoom meeting on teaching history this Saturday, September 28th at 2pm EST. The meeting is open to all subscribers. See post for details:

Teaching History & Ask Us Anything

Final Words

Owning a wide-ranging collection of history books doesn’t just give us an Ikea shelf overstuffed with dusty unread volumes.

Knowledge is power, and of all the forms of knowledge, history is one of the most valued by elites. Elites know that those who control the story of the past control the story of the future. Convince a person of who they were or what they did, and you can convince them of what they need to do and who they need to become.

Owning our own print history books won’t free us from the flaws and biases in these books—an ever-present challenge in all writings about the past. But it does eliminate the risk that our knowledge will be digitally curated by corporate or political forces whose real interest is not history but power.

So, start collecting your history books today. Add them to your book monastery and liberate yourself from the grip of remote digital knowledge management and the flavors of faux history. You’ll thank yourself for it one day, when the memory of the world becomes confused or starts to fade.

Or else your children will thank you.

People are always shouting they want to create a better future. It’s not true. The future is an apathetic void of no interest to anyone. The past is full of life, eager to irritate us, provoke and insult us, tempt us to destroy or repaint it. The only reason people want to be masters of the future is to change the past.

– Milan Kundera, The Book of Laughter and Forgetting

A tremendous THANK YOU to everyone who contributed recommendations!

Are there any books that you would add to our list?

Which ones have you found particularly insightful?

Please share your reflections in the comments section!

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), please consider supporting our work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a like, restack, or share!

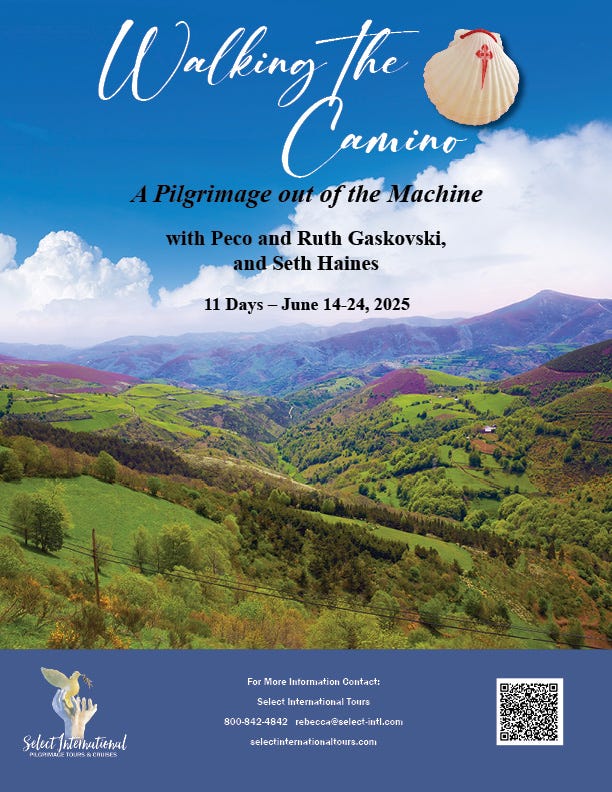

Come and join us on A Pilgrimage out of the Machine!

My husband Peco and I will be leading an eleven-day pilgrimage on the Camino trail in Spain next year, from June 14-24, 2025. Joining us, as co-leader, will be writer/photographer Seth Haines from The Examine. Space is limited so reserve your spot now :) You can read all about it here or view the brochure here. This trip is open to everyone, irrespective of religion or background.

Further Reading

A Guide to Booklegging: How (and why) to collect, preserve, and read the printed word

The Front Page: Tucker Carlson and the War Against History by

forGoogle Thinks Beethoven Looks Like Mr. Bean. Instead of real portraits, Google serves up AI-generated garbage by

Our use of this word is loosely inspired by Ray Bradbury’s use of “blanc-mange” in his coda to Fahrenheit 451:

Every dimwit editor who sees himself as the source of all dreary blanc-mange plain-porridge unleavened literature licks his guillotine and eyes the neck of any author who dares to speak above a whisper or write above a nursery rhyme.

While I tried to include most of the recommendations I may have missed some, or left some out because they did not specifically address the question posed.