A Guide to Booklegging: How (and why) to collect, preserve, and read the printed word

Semantic mountains, mind communion, and building your book monastery

The bookleggers smuggled books to the southwest desert and buried them there in kegs. The memorizers committed to rote memory entire volumes of history, sacred writings, literature, and science, in case some unfortunate book smuggler was caught, tortured, and forced to reveal the location of the kegs…

The project, aimed at saving a small remnant of human culture from the remnant of humanity who wanted it destroyed, was then underway.

from A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller

Part I: Semantic Mountains (by Peco)

Move fast and break things was the internal motto of Facebook (Meta) until 2014. It’s no longer their motto, or so they say. But even today, move fast and break things seems to express the operating principle of many Big Tech companies, in that the “success” of a new technology doesn’t only depend on the speed at which it can be developed and rolled out to the public, but it’s ability to bulldoze and demolish anything that stands in the way of innovation.

But for fast things to thrive, slow things must die.

Books are slow. They take time to write, and once they are written, they don’t move much. The words sit on the page; the pages are nestled in the binding; the book stands on the shelf until somebody takes it down and reads it; and then it goes back on the shelf. It doesn’t change, and this non-changingness matters. In a world where technology floods through our lives, breaking things fast, print books are semantic mountains whose peaks rise above the waters, stable and unmoving in the midst of the chaos.

Books preserve historical memory and knowledge. Of course not all books are good books; some contain serious biases. Even the great ones have their limitations. But books don’t have the perfidious problem that AI-generated content does. We might call it the Gemini problem.

Most of us know that Google went through a global embarrassment when it’s generative AI model, Gemini, produced bizarre responses to historical prompts, like showing a Native American man and Indian woman as an example of an 1820s-era German couple (and historically weirder things than that). According to Google SVP Prabhakar Raghavan, the problem was that the design of the system led it to “overcompensate in some cases, and be over-conservative in others.”

Google promised to fix the problem, no doubt by compensating less where it previously over-compensated. But by how much? Who will decide when the balance is right?

The bias in Gemini will never be adequately fixed, because human beings—who design AI systems—are also biased. We see that in books too, of course. Some books will tell a history one way; another will tell the same history another way. To that extent, it might seem that printed books are no safer than AI-produced content or other digital content. But there is a difference.

Books are stubbornly stable. Once the words are printed on the page, we can be certain that certain words will not mysteriously change or vanish because somebody in Silicon Valley has tapped a button to adjust the “overcompensation”, or that dates of important events will slide around depending on the changing moods of society.

AI exists in an eternal a-historical present. If its parameters are designed to modify words, dates, events, and other content, it will do so unthinkingly; and if that AI model is prevalent throughout society, we will absorb these changes unthinkingly. When we read digital content produced by AI—particularly stories, opinion, and emotionally or value-laden text—we are opening ourselves to manipulation by a digital system, for the profit or power of a small minority behind the machine.

If we give up our print books, we are giving up our semantic mountains. Without those mountains, we have no stable refuge of social and historical meaning. We will be tossed in floodwaters that move fast and break things, including the knowledge and stories, and traditions that have been thoughtfully curated over centuries.

Communing with books

Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realise the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors ... We realise it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated. The man who is contented to be only himself, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others.

C.S. Lewis

Print books aren’t just anchors of historical memory. They are ways of connecting our mind to the minds of other people we may never meet. Somebody saw something in their imagination, or came to a new understanding, and translated that into words on a page. We see those same words and translate them back into our own imagination or understanding—and somewhere in that cognitive exchange, our mind and the mind of another human being come into contact.

This is a form of communion; it’s part of our need to connect with other people. Years ago, when we lived on the east coast of Canada, I was hiking through a blueberry field overlooking the Atlantic Ocean, talking about books with an old friend. I was still twenty years away from publishing my first novel, and I wanted my friend’s opinion on what defined a good story. My friend admitted he didn’t read many novels. But of what he did read, it wasn’t the story that mattered to him; not the plot, not the genre, not the power of the language. It was experiencing a sense of relationship with the story. A feeling of kinship with the book. As if, for him, a good book was more like a friend than a story.

There is no human being behind AI-produced content. There is a vast digital system that trains itself—essentially plagiarizes and cannibalizes—the words of real people, and reconstructs them to produce the semblance of a human author. When we read AI-produced content, we are not communing with a person, not even a machine. There is no communion at all.

AI-produced content has the power to manipulate our values and how we spend our money, but it can do something else. The more customizable AI becomes, the more it will generate content that focuses on our own feelings, needs, and identities. Like many unhealthy forms of social media, it may cultivate a self-orbiting tendency that can verge on narcissism.

Books can do this too if we read narrowly, but books—especially print books—are not otherwise customizable. Their identities are stubbornly fixed. A paperback won’t instantly change its content because we pick it up and whisper, “Tolkien, can you make Sauron a good guy, please?”

One of the vital powers of good books is that they can dislodge us from our own perspectives, and situate us within the perspectives of others. We may enter the mind of an author who inhabits a world very different from our own. In the case of authors who are no longer alive, we are engaging in cognitive archeology: wandering through the remains of someone’s past, with all its strange sights and peculiar relics. This, too, can de-center us, deflecting our self-orbiting tendencies.

AI’s relics are all stolen from other lives. AI content is identity theft on a gargantuan scale. AI might one day write a “great book” in the technical sense, and triumph over the imaginations of many readers; but the triumph of the technique will be a hollow accomplishment. We cannot come into contact with an authentic life through a machine that has no authentic life.

For now only a fraction of society—the “radars” among us—are concerned about any of this. In the meantime generative AI has arrived. A viral tweet in 2023 asked us to “imagine if every Book is converted into an Animated Book and made 10x more engaging. AI will do this. Huge opportunity here to disrupt Kindle and Audible.”

One tech commentator has suggested that claims like this are absurd, as people who read books don’t want their books to be disrupted. But it would be a mistake to underestimate generative AI. It’s going to move fast and break things, and that could include any semantic mountains that get in its way.

We don’t have to be passive and wait for this to happen. We can build up our semantic mountains. If AI feeds us low-quality content, we can seek great books that have been curated by the brightest and most creative human minds across the centuries—from Tacitus to Toni Morrison, from Plutarch to Pasternak.

We can turn our homes into book monasteries, populated by silent monks who stand patiently on their shelves, waiting for us to commune with them. We can preserve and carry on the best of human society, one that will live on long after the floodwaters of digital dross fade away.

For man was a culture-bearer as well as a soul-bearer, but his cultures were not immortal and they would die with a race or an age, and then human reflections of meaning and human portrayals of truth receded, and truth and meaning resided, unseen, only in objective logos of Nature and the ineffable logos of God. Truth could be crucified; but soon, perhaps, a resurrection.

from A Canticle for Leibowitz by Walter M. Miller

Part II: Make your home a book monastery (by Ruth)

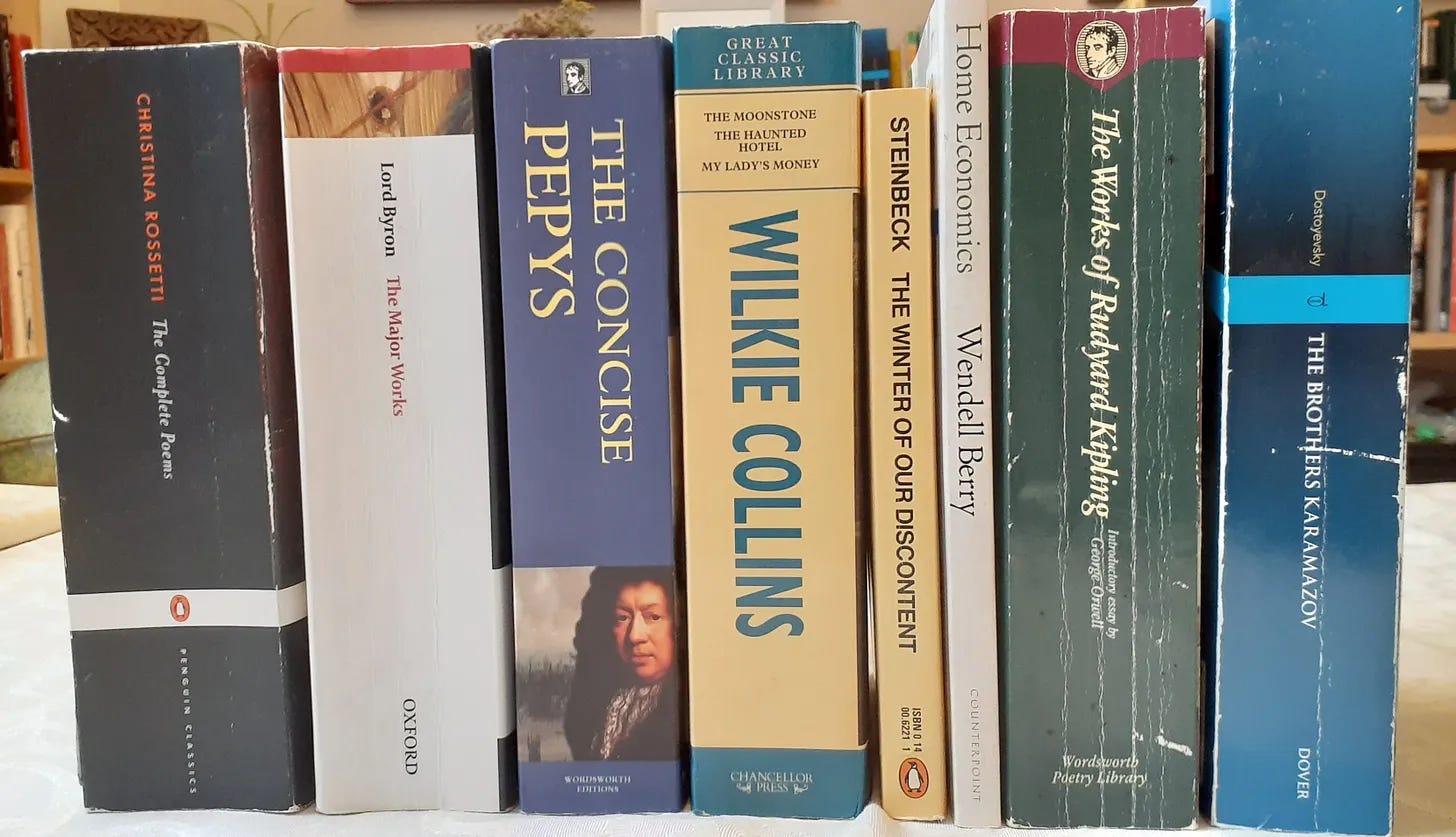

A few weeks ago I made my rounds at one of the local thrift shops and stopped cold as I looked at the “Classic Literature” section. The shelves which had been quite fully stocked just a few days prior, were suddenly half bare and now featured oddly categorized “classics” such as Manga comics and the Vagina Monologues. Books on these shelves never sell out this quickly, but young staffers remove volumes at whim to be moved into storage or worse, the dumpster1.

As I picked up a copy of Brothers Karmazov, I noted that it was marked with the lowest price tag ($2.49). The same was true the collected works of Rudyard Kipling, Wilkie Collins, and many other classics. I realized that the availability and assigned value of books lay in the hands of teenage employees, who clearly viewed these works as worthless. I promptly bought a stack, saving them from possible careless discard.

This experience reminded me sharply of the idea of “booklegging” in Miller’s dystopian novel A Canticle for Leibowitz. While I certainly did not feel the need to smuggle books to save humanity, I realized that classics may well slowly disappear from shelves. They have already made a steady retreat from libraries, many of which pull books out of circulation2 if they have not been checked out within a given time frame. Bookstores, which

aptly describes as “ Starbucks franchises that have a Colleen Hoover section”, continue to reduce and narrow their stock. Add to this the poisoning of the internet groundwater by what termed “AI pollution” and the time begins to appear ripe to take the collection and preservation of physical books seriously.Peco and I have been collecting books for over two decades and, in addition to the shelves that frame each room, have added a dedicated library in our home. We share our books with friends if they would like to borrow a volume and also pass some books on in our Little Library on the front lawn. I have always dreamed of creating a home that C.S. Lewis experienced as a child, where he had “the same certainty of finding a book that was new to me as a man who walks into a field has of finding a new blade of grass”.

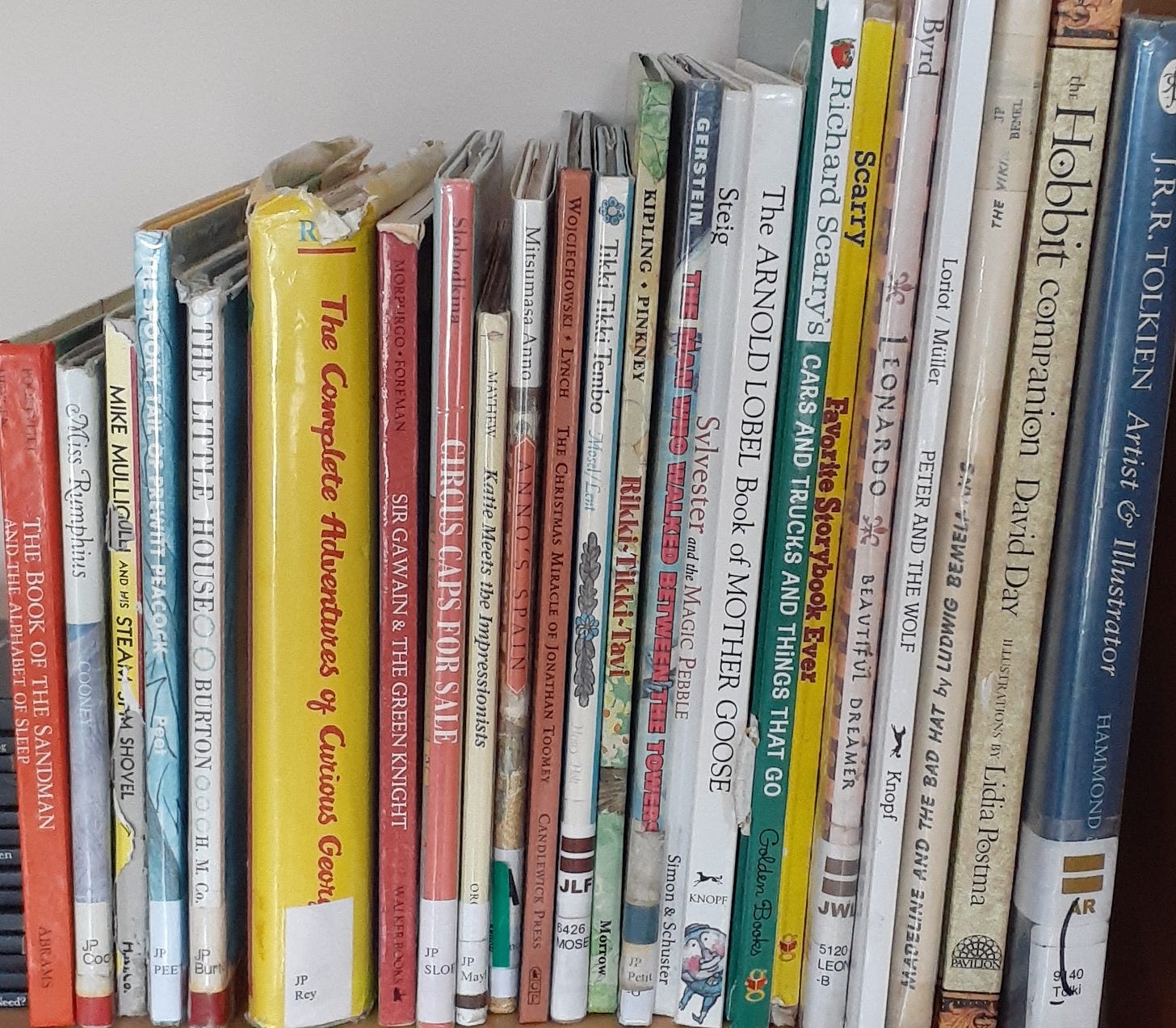

Our collection spans a great variety of books: the ancient Classics, history books, Bibles in various translations (and languages), classic and modern literature, biographies, theological books, non-fiction reference books, art collections, , poetry, textbooks, children’s and picture books, and many that fall somewhere between these categories.

We have not read all of the books we own, but resonate with Umberto Eco’s approach of living surrounded by books3.

recently shared this photo of a “small section” of Umberto Eco’s library (if you want to feel truly awed, watch him walk through his library in this brief video). While few of us will likely aim to fill our homes with 30’000 books, the value of building an “antilibrary”, a collection of books that we have not yet read, keeps us humble by reminding us of what we do not know.4(Note: My teenage son just reminded me to add, that our home looks nowhere near as filled with books as this)

It is foolish to think that you have to read all the books you buy, as it is foolish to criticize those who buy more books than they will ever be able to read. It would be like saying that you should use all the cutlery or glasses or screwdrivers or drill bits you bought before buying new ones…

Those who buy only one book, read only that one and then get rid of it. They simply apply the consumer mentality to books, that is, they consider them a consumer product, a good. Those who love books know that a book is anything but a commodity." – Umberto Eco5

Staples to Stock Your Pantry

All civilization comes through literature now, especially in our own country. A Greek got his civilization by talking and looking, and in some measure a Parisian may still do it. But we, who live remotely from history and monuments, we must read or we must barbarise.

from The Rise of Silas Lapham by William Dean Howells, 1885

Just as you would stock your kitchen pantry with certain staples used for most basic dishes, there are literary staples that build a solid foundation for your collection. As Susan Wise Bauer has observed, this foundation in turn allows us to join what Mortimer Adler referred to as “The Great Conversation” of ideas that date back to ancient times and continues uninterrupted to the present day.

In The Well-Educated Mind, Wise Bauer explains the value of classic literature:

Writers build on the work of those who have gone before them, and chronological reading provides you with a continuous story. What you learn from one book will reappear in the next. But more than that: You’ll find yourself following a story that has to do with the development of civilization itself.

So where to start?

I concur with Wise Bauer that “List making is a dangerous occupation”, as no list is authoritative, nor complete, nor unbiased, as each reflects the values of those who curated it. Thus, take the suggestions shared here as a starting point and build or amend to your liking.

Peco and I have found the following collections helpful:

For Adults:

The Great Books6 - History as Literature by Susan Wise Bauer

The Harvard Classics first complied by Dr. Charles W. Eliot in 1909

1001 Books You Must Read Before You Die edited by Peter Boxall, and written by over 100 hundred international critics.

Top 100 Works in World Literature -The editors of the Norwegian Book Clubs, with the Norwegian Nobel Institute, polled a panel of 100 authors from 54 countries on what they considered the “best and most central works in world literature.”

The Top 10: The Greatest Books of All Time - Contains 103 Books; Top 10 books chosen by 125 top writers from the book "The Top 10" edited by J. Peder Zane.

The Mensa reading list for grades 9-12 is also an excellent, extensive source to get started for adults.

The Thousand Good Books - Great Books of the Western World

The Greatest Books site is an excellent resource with 251 lists including Greatest Books of All Time Written by Women, Africa’s 100 Best Books, Favorite Books of Spanish Authors, Best Foreign Works Chosen by Francophone Writers , 100 Books to Read from Eastern Europe to Central Asia

If you are interested specifically in books that highlight the negative impact of technology on what it means to be a person, the importance of digital minimalism, or something that metaphorically expresses the dangers of technology as one of its primary themes, have a look at the list we curated based on our reading and on recommendations from

, , and many motivated readers:

For Kids and Youth

Read Aloud Revival Book Lists -These lists include some classics but also contemporary book choices. Here is a selection (there are still more groups on the site):Books Boys Love; Books Girls Love; Books for Ancient History; Books for Middle Ages & Renaissance

The Thousand Good Books - from nursery and gradeschool, to adolescent and young adult

Collecting books does not have to be expensive. We rarely buy new books and obtained the majority from thrift stores, recycling depots, library sales, community book sales, garage sales, or from friends who moved. They can also be ordered inexpensively from online used booksellers such as alibris.com or thriftbooks.com.

Please Note: While we focus here on collecting physical books, we also recognize the value of audiobooks and CDs. Audio versions can be particularly helpful for younger readers, readers who prefer auditory to visual input, or readers who experience eye strain. For an excellent exploration on audio vs. print books see

’s post Do Audiobooks Count?“None of us can fully escape this blindness, but we shall certainly increase it, and weaken our guard against it, if we read only modern books. Where they are true they will give us truths which we half knew already. Where they are false they will aggravate the error with which we are already dangerously ill. The only palliative is to keep the clean sea breeze of the centuries blowing through our minds, and this can be done only by reading old books. Not, of course, that there is any magic about the past. People were no cleverer then than they are now; they made as many mistakes as we. But not the same mistakes. They will not flatter us in the errors we are already committing; and their own errors, being now open and palpable, will not endanger us.”

C.S. Lewis

Old Books

My favourite category to collect are old books. While you can get modern editions of classic works, there is a sublime pleasure in reading a book that is inhabited by time (maybe this is just me?). Several years ago I saved a civil war poetry book from the recycling depot that was printed in 1865. I contained a beautifully penned inscription. Reading through the poems is ever more moving knowing “Mary” thought of her brother while her hands held the same book almost 160 years ago.

I also learned an important lesson about older editions: a single book was sometimes printed in several volumes. Oblivious to this fact, I came across three 1894 editions of The Count of Monte Cristo at a “free bookshelf”. Not wanting to be greedy I took only one, leaving the remaining two to be enjoyed by others. When I started reading the book I found it rather disorienting and found myself a bit lost among the unexplained characters. Yet I persisted and got fully absorbed in the story until I reached the last page, which stated: End of Vol II. I never did locate the other two volumes, but instead had to buy a modern edition beginning again from the start. To this day Dumas’ classic remains one of my all-time favourites.

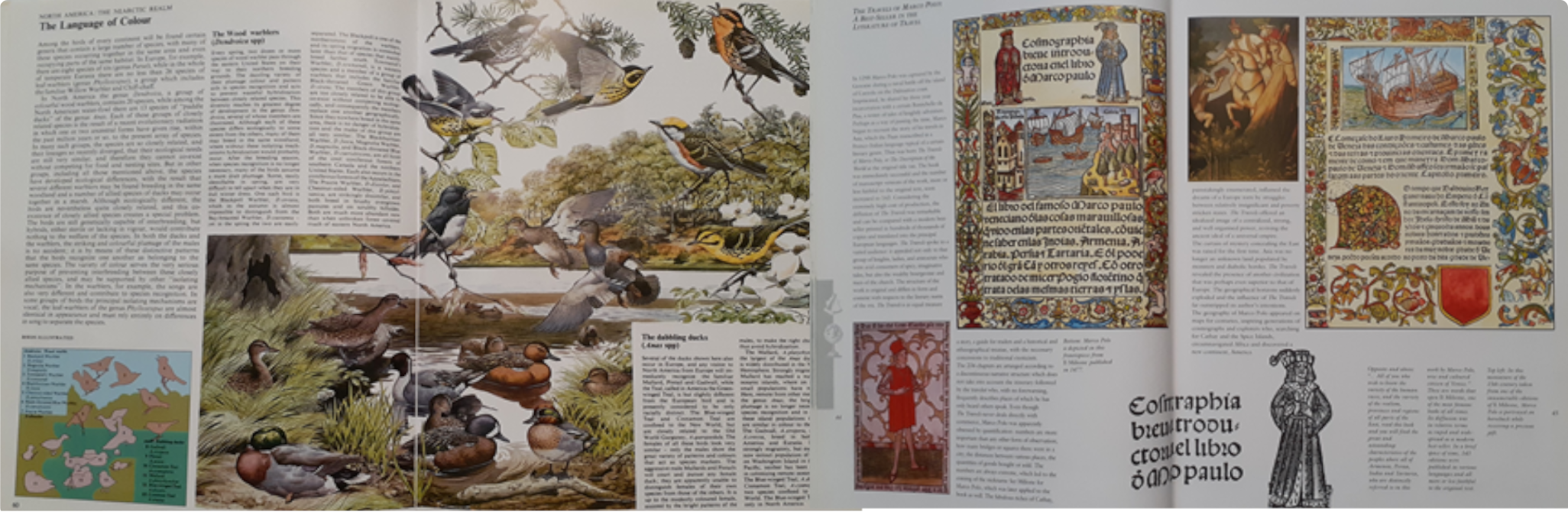

Reference Books & Dictionaries

The internet is generally upheld as the pinnacle of ready reference. This is certainly true with regard to speed and apparent efficiency. Yet with the ever-increasing deluge of content, it can be challenging to discern accuracy and reliability, filter out constant distractions, and avoid irrelevant rabbit holes and excessive hyperlinks.

In contrast, reference books list the credit of experts chosen from their field for their authoritative knowledge on the subject. Photographers and interior designers package the information beautifully (and without pop-up ads). Importantly, although these works may be several hundred pages long, they are not infinite. This limitation allows for consolidation of knowledge, as you can flip through identical pages over and again. These physical references thus create zones of familiarity and better support and consolidate learning.

The same is true for physical dictionaries. While the search may be less efficient, this added time entails the benefit of incidental learning. Flipping through pages to locate the word we are seeking de-centers the search and allows us to discover additional words and definitions (e.g. when looking up cirrocumulus —a cloud which is composed of the cumulus broken up into small masses, presenting a fleecy appearance, as in a mackerel-back sky—I also see the an unfamiliar word just above, cirriped —A general term, applied to animals of the barnacle kind. The feet are long and slender, and curve together into a kind of curl).

When using especially old editions, we discover etymologies, instances of use, and also glean historical knowledge9. This 1854 Webster’s Dictionary Pictoral Edition is my younger son’s favourite, and the knowledge that writers like Mark Twain or Henry James may have used the same reference adds to the enjoyment.

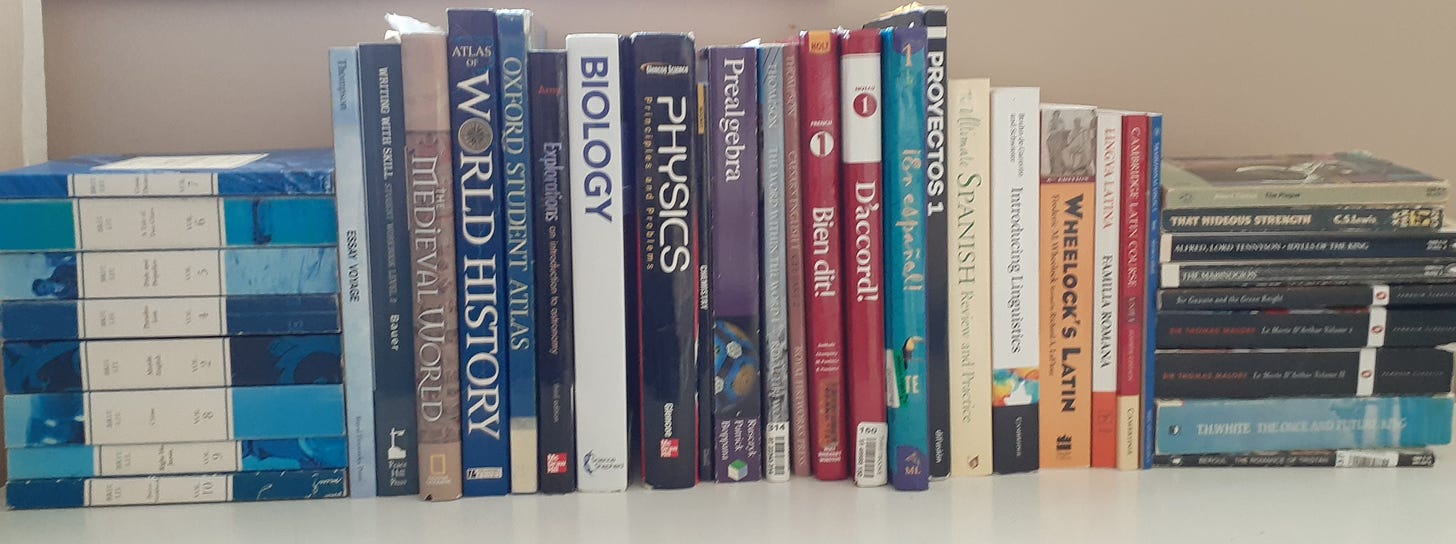

Textbooks

When a printed book - whether a recently published scholarly history or a two-hundred-year-old Victorian novel — is transferred to an electronic device connected to the Internet, it turns into something very like a Web site. Its words become wrapped in all the distractions of the networked computer…The linearity of the printed book is shattered, along with the calm attentiveness it encourages in the reader.

from The Shallows by Nicholas Carr

Many textbooks are now available in online versions touting heaps of interactive features. Yet the fact that the content to be studied is channelled through the same screen from which students have come to expect entertainment and notifications, places it in a distracted sphere. Digital textbooks not only decrease focus, but make it exceedingly difficult (and dizzying) to skip between sections or chapters for reference. Studying with a physical textbook in hand, marking of important passages or terms, flipping pages, etc. locates the learned knowledge in real space. So, whenever possible, obtain physical textbooks which will facilitate learning and support better attention and focus.

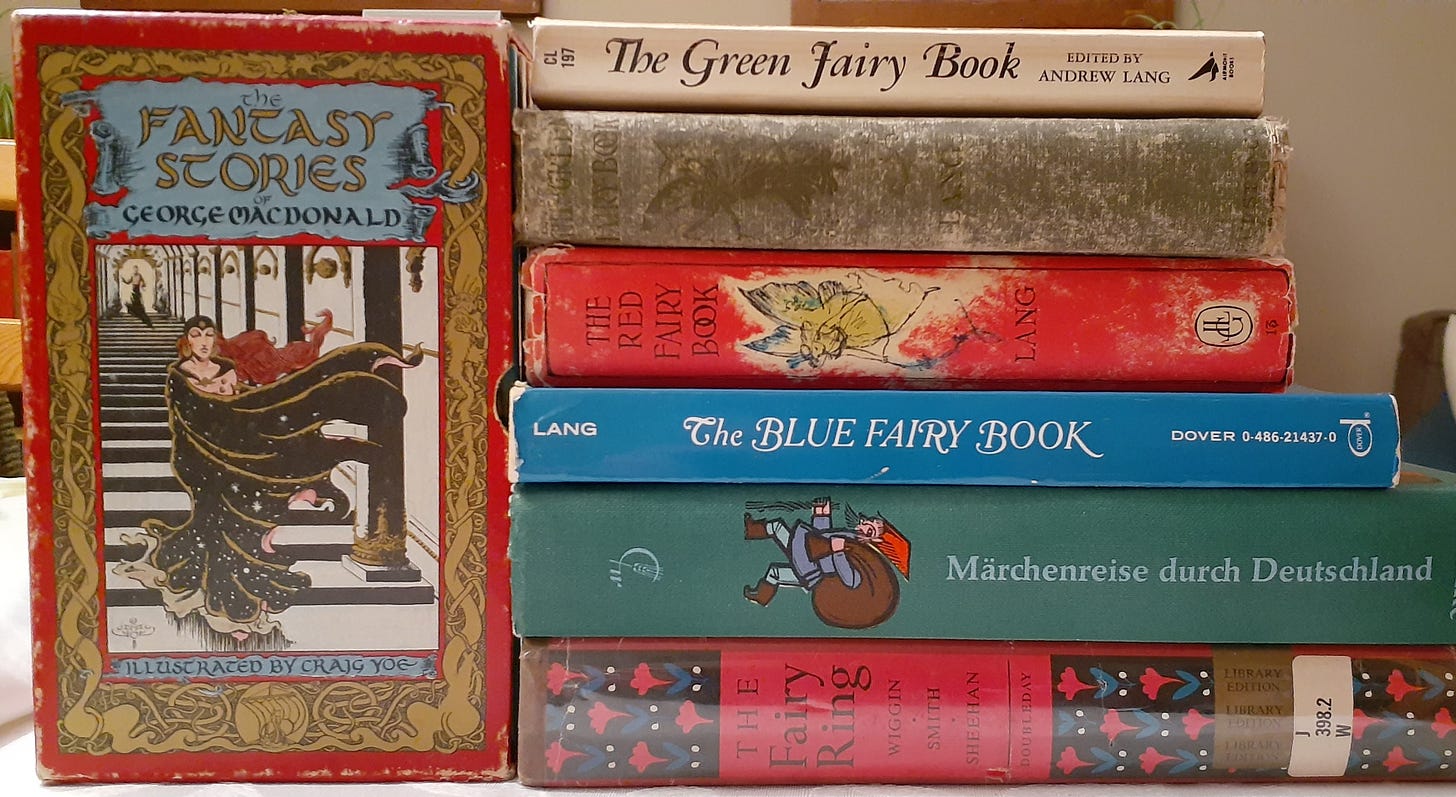

Fairy Tales

If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.

Albert Einstein

Necessity is the mother of invention, but sometimes necessity is a father. Starting when our daughter was three or four, Peco began to tell her stories each night before she went to bed. The necessity was that he loved her, and couldn’t bear to say goodnight without giving her the funniest or most whimsical or exciting tale he could think up on the spot.

He tried not to skip any nights, and the storytelling continued through the birth of our first son, and lingered for a few years after through the birth of our second son (although now it became more challenging, as he had to devise stories that both older and younger children could follow). He estimates that he told around 2000 stories, though might have been a few hundred more or a few hundred less.

While not every parent is such a natural storyteller, we can dig into fairy tales that have captured listeners for centuries.

If you are interested in discovering some “weird and wonderful” tales outside the standards of the Western canon, Peco and I encourage you to check out the newly translated Slavic fairy tale collection by

(who is a fantasy writer and instructor at St.Basil Writer’s Workshop along with and ). You can read all about the collection on his kickstarter page which just launched yesterday. Here you can listen to Kotar’s wonderful rendering of The Tale of Prince Ivan and the Grey Wolf:Picture Books

When our children were younger, one of my favourite parts of the day was our early morning reading time on the couch. We would pile together with a stack of picture books on the coffee table in front of us and work our way through. The weekly library visits provided a continuous supply of new books (our library had a limit of 100 items which we surprisingly reached at times). Spending time reading classic picture books is the perfect antidote to what

describes as “incoherent dream-slop”, as the story lines are solid, characters are developed, and your engagement with your child while reading supports them in making meaningful connections.Our children still have a deep fondness for these stories and intend to keep the books to read to their children in turn. Thrift stores and library sales are excellent places to build your collection.

The Language of Classic Books

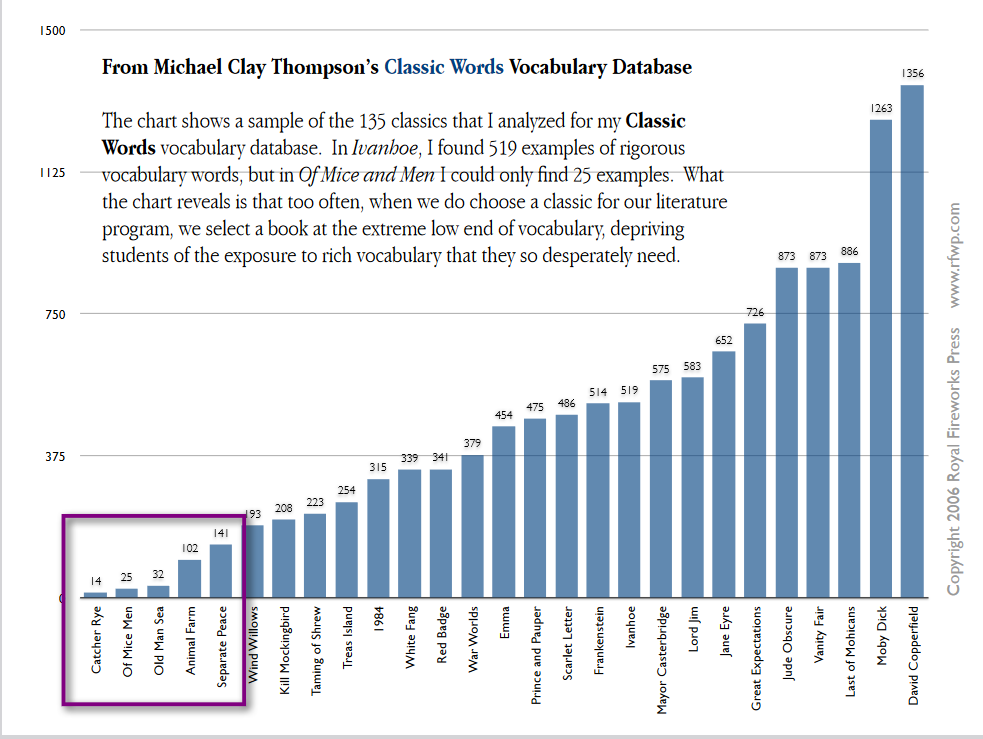

Many classic books that contain a rich cornucopia of language, have been pulled from school curricula because they are deemed too complex, too inaccessible, or simply irrelevant. Long-time readers will recognize this classic vocabulary chart by Michael Clay Thompson which I shared in Raising Writers Against the Machine last year. It shows that classics which are still taught in schools hold a mere vestige of the vocabulary10 which was once considered essential for good communication. In her article Are Books Dead?

relates that English teachers in her daughter’s high school leave out books all together and only assign short stories and articles instead.When embarking on the journey to read or collect classics, many readers feel daunted by the complexity of advanced vocabulary richly peppered throughout older books. As a second language learner, I recall reading the Hobbit for the first time with a German-English dictionary in one hand, and the novel in the other. I thus have an appreciation for struggling through texts, and an even greater appreciation for the work by educator Michael Clay Thompson, who wondered over 20 years ago what the best words in the English language were.

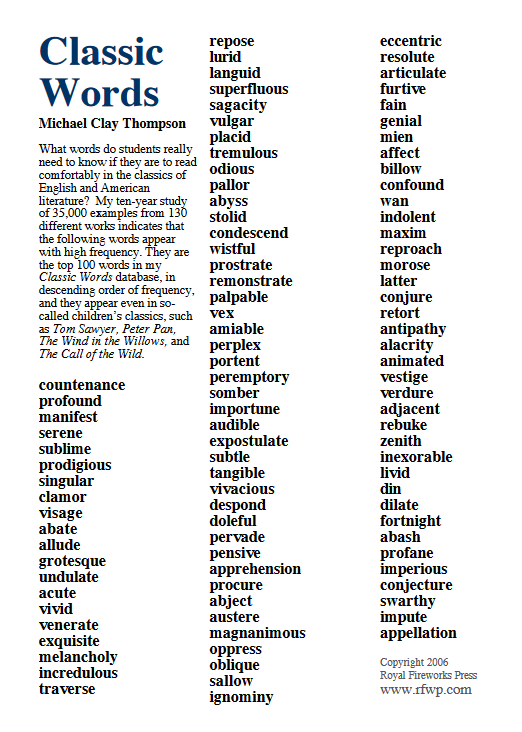

As an educator who develops language arts curricula for gifted children, Thompson began marking advanced vocabulary in every English language classic that he read, a task which eventually developed into a ten-year study of 35,000 examples from 135 different works. From his research he distilled the top 100 words that appear with high frequency in classic works of English and American literature.

Studying the words on this list will help you comfortably access the language of classic literature.

Finally, more than half of commonly used English words and over 90% of multisyllabic ‘big’ words derived from Latin. Learning even just 100 of the most common Latin stems in the English language gives you access to at least 5000 words.

In the Family & Education section (which also contains a complete classic vocabulary study for Dickens’ A Christmas Carol), paying subscribers have access to the Latin and Greek stem resources (practice, flashcards, and quizzes) I have developed for the children in my homeschool co-op. You can download the first list for free in this post.

We hope this post will inspire you to join the ranks of bookleggers, build a book monastery, and create a refuge where you can commune with great minds and that can be passed on to the coming generations.

What staples do you stock in your book pantry?

How do you decide what books to add?

Are there any additional categories of books in your home?

Where do you find your books?

Please share your thoughts, reflections, and questions in the comments section!

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), and if you would like to support our work of putting together a book on “The Making of UnMachine Minds”, please consider supporting our work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a like, restack, or share.

You can also support us via our brand-new Unconformed Bookshop11 , as far as we know, the only one dedicated to books on unmachining.

Further Reading

The Truth About Banned Books by

forHow I Read - Non-secrets for voracious reading by

Are Books Dead? Why Gen Z doesn’t read by

Three Wonderful Limitations of Books by

The Irresistible Physicality of Books by

Reflections for a Sunday: "Only paper is safe." by

Books in our homes - How books shape our family lives by

How John Steinbeck tricked his kids into reading books by

Earlier this week as I dropped off my daughter at university, I glimpsed a student employee pushing a cart loaded with books behind the building. There, to my dismay, he began to toss each fat volume into the dumpster. I debated whether I should venture over and offer to rescue the remnants, but drove on with a feeling of faint pain.

Due to the “if not checked out for one year then discard” policy at our library, I was able to acquire an entire series of encyclopedias on the medieval era, DK reference books, countless novels, and heaps of children’s classics.

Writer and homeschool educator

and her family have literally turned their home into a type of book monastery containing 13’000 volumes. Several years ago they created a separate library space which they opened up to local families, and in doing so, have created a community that grew naturally around the weekly visits. You can read about this twenty-year journey in her article “The Accidental Community”.The Mensa program provides wonderfully extensive reading lists students starting with kindergarten all the way to high school. The books can be read independently by the student, read aloud by the parent, or listened to as an audiobook (also, when a student completes a reading list, they receive a certificate of achievement and t-shirt).

This is one of my favourite reading lists: a superb collection of books sorted according to grade/lexile levels.The recommended books for grades 3-up are in three categories: (1) classics (2) light reading (3) informational reading.

If you are up for an informative diversion, you can test your English vocabulary here. It takes just a few minutes to complete and provides an estimate of your acquired vocabulary (for English speaking adults between 20’000 and 35’000). It may also lead you to look up what in the world words such as hypnopompic, fuliginous, or tatterdemalion mean.

Every purchase goes to support independent bookstores across the country and also supports our work here :)

"Never try to start an argument with a person whose TV is larger than his bookshelf." -anon

Excellent Ruth and Peco. A home library is such an important resource. I have an extensive collection of nature field guides which I love looking through and marvelling at the contents of. There are species I would never have heard of if it wasn't for these books, and the ability to identify obscure dragonflies, moths, birds, and flowers that I see is invaluable (this information is really hard to access on the internet for some species groups).

Reading information in books also adds worth/value to that knowledge. When my father was young, if he wanted to find out something about Japanese history, he would have to cycle to the local library, find the book, find the part he wanted to read, and then take notes. You can be sure he valued and treasured such knowledge considering how much effort it took him to obtain. And the memory of the process of obtaining the information helped him remember the information he gleaned.

Conversely, we live in a world of inform action overload - cheap, easy to access information that we often forget the same day that we read it. I know this experience all too well in my own life. I am much more likely to remember something I read on a paper page than on a screen.