Rehabilitating Ferals of the Digital Age

Eating books, training deep attention, and a practical guide to reading

Our recent transatlantic flight from Switzerland back to Canada proved to be an “accidental detox” for passengers, as to the horror of most, there were no screens on the seat backs, and no charging ports for devices. After the first gasps of surprise and dismay (especially of parents with small children) subsided, a wonderful scene unfolded. I had no idea so many people still read books! The photo below is the view across the row from me. The plane was humming with conversation; two men behind me who had never met before, struck up a conversation (a joy to listen to Scottish accents) and shared beers and stories, children played paper games, and our family rotated through reading Thomas Hardy, Seinfeld scripts, Ian McEwan, C.S. Lewis, and Calvin and Hobbes (something for every age and interest). It seemed like a flight in a time machine, where people still remembered how to converse, play, read books, and spend time away from black mirrors.

The following day

pondered aloud on Notes, if people were to jettison their screens, how long it would take for minds and attention spans to return to “normal”, leading to wonder further, “We Gen-X and older have a default to go back to. What do we do for people born after 1995 who don’t?”Thinking about this question more deeply, I realized that the offspring of the digital age have grown up as attentional and relational ferals. Many have grown up isolated from deep attention from a very young age, have social behaviour stilted by online interactions, and suffer from emaciated language skills. While the “accidental detox” flight did ignite some hope in me regarding people’s ability to engage their minds differently, this scene could only occur because people were left no other choice. I am also quite sure that that everyone quickly reverted to their usual patterns of distraction as soon as they were off that flight.

There are a myriad of things that make us human. But the ability to pay attention lies at the core. Relationships require attentive listeners; learning takes dedicated attention to grow knowledge and skills; reading demands attention to words, meaning, and context; work demands attention to produce carefully crafted products or services; democracy involves attention to truth and opposing positions; faith requires attention for prayer, silence, and reading scripture. Attention is it.

When deep attention has to compete with hyper attention (fractured attention that quickly zips from one point of focus to the next), it is akin to throwing a dolphin into a tank filled with piranhas and hoping that they will find a way to coexist. Although we are prone to fool ourselves, there cannot really exist a “healthy balance” between dolphins and piranhas.

I discussed this attentional issue in a couple of earlier articles (such as TikTok-Time is running out for saving our children's brains), relating accumulating research on the detrimental effects of digital device use, especially on children and youth. In this Wall Street Journal article, Michael Manos, clinical director of the Center for Attention and Learning at Cleveland Clinic states that, “Directed attention is the ability to inhibit distractions and sustain attention and to shift attention appropriately…If kids’ brains become accustomed to constant changes, the brain finds it difficult to adapt to a non-digital activity where things don’t move quite as fast.”

The current generation is habituated to switching tasks every few seconds. Indeed in 2017, before the new crop of social media apps, a study found that even undergraduates, who are more cerebrally mature than K–12 students and therefore have stronger impulse control, “switched to a new task on average every 19 seconds when they were online.” 19 seconds. I cannot think of one coherent task that only takes 19 seconds to fully complete. Even brushing your teeth takes longer.

Paul Bennett, the director of Halifax-based firm Schoolhouse Institute and adjunct professor of education at Saint Mary’s University explains that, “the more time young people spend in constant half-attentive task switching, the harder it becomes for them to maintain the capacity for sustained periods of intense concentration. A brain habituated to being bombarded by constant stimuli rewires accordingly, losing impulse control. The mere presence of our phones socializes us to fracture our own attention. After a time, the distractedness is within us.” Near constant distraction by phones and other tech has serious side-effects, especially for reading. No wonder that by 2016, just 16 percent of 12th-grade students read a book or magazine on a daily basis.

This post is not intended as a lament, but as a starting point for rehabilitating attentional ferals of the digital age, whether they be young or old. All of us who use digital devices are affected by the easy lure of hyper attention, and if our aim is — as

suggests, “to be anchored to our core meanings in life and situate technology’s proper place in the order of things” — then it is up to us to train, grow, and reestablish deep attention.On eating books

In order to reclaim our attention, deciding to start with a digital detox can be a helpful first step (see From Feeding Moloch to Digital Minimalism for a concrete game plan). With regard to actually training the mind to refocus and develop deep attention, reading books provides the best rehabilitation. This not only for attention’s sake, but because books allow us to dig our minds into the humus of time, people, and civilization as a whole.

In his essay In Defense of Literacy, Wendell Berry explains the importance of reading books as follows:

I am saying then, that literacy - the mastery of language and the knowledge of books - is not an ornament, but a necessity. It is impractical only by the standards of quick profit and easy power. Longer perspective will show that it alone can preserve in us the possibility of an accurate judgement of ourselves and the possibilities of correction and renewal. Without it, we are adrift in the present, in the wreckage of yesterday, in the nightmare of tomorrow.

In other words, without the knowledge of books and mastery of language, the nightmare of tomorrow may well turn us into what

refers to as “thin humans”, forever on the surface of things, “the surface of time, by forcing too much hurry and efficiency; the surface of relationships, which will be shallower and more functional; the surface of information, which will keep us credulous; the surface of our own thoughts and feelings, which will keep us alienated from our own depths.”In contrast, extensive knowledge of books and the wisdom transmitted through the authors behind them expands us into a fuller, more rooted human being. We gain intellectual nourishment, personal insights, and a deeper understanding of the world around us from tasting, eating, and digesting books. In An Experiment in Criticism, C.S. Lewis explains,

“Those of us who have been true readers all our life seldom fully realise the enormous extension of our being which we owe to authors,” ... “We realise it best when we talk with an unliterary friend. He may be full of goodness and good sense but he inhabits a tiny world. In it, we should be suffocated. The man who is contented to be only himself, and therefore less a self, is in prison. My own eyes are not enough for me, I will see through those of others.

According to Susan Wise Bauer, men and women have been undertaking self-education based on reading and discussing books for centuries: “Any literate man [or woman, we would add] can rely on self-education to train and fill the mind. All you need are a shelf full of books, a congenial friend or two who can talk to you about your reading, and a ‘few chasms of time not otherwise appropriated’”.

Earlier this year

, who writes The Honest Broker, started a small firestorm of enthusiasm by sharing his Lifetime Reading Plan (prompting other writers such as to share theirs in turn). He richly describes the path of his self-education and details his “orca-sized time blocks” devoted to reading. Notably he admitted to being a slow reader, affirming that reading fast has nothing to do with being well-read. In The Well-Educated Mind, Susan Wise Bauer supports this notion by stating, “The idea that fast reading is good reading is a twentieth-century weed, springing out of the stony farmland cultivated by the computer manufacturers…The speed ethic shouldn’t be transplanted into an endeavour that is governed by very different ideals.”A Practical Guide to Reading

Read physical books

In Reading as Counter Practice,

discusses Maryanne Wolf’s research on the importance of reading tangible books. This includes the way in which a book provides cues to the embodied mind:….visual placement on a page or the shifting weight of one side of the book against the other as we make our way through it - which subtly scaffold our comprehension and retention. And, and of course, the book is not also the gateway to countless other forms of media the way a smartphone, tablet, or even internet-connected e-reader might be. In these ways, the affordances of the books might be uniquely suited to sustaining deep reading.

Reading a book on any kind of screen keeps your mind in “device mode” and will likely lead to greater struggles maintaining attention. On that note, keeping devices away from your body and out of reach and sight helps to redirect your mind toward the book in hand. Devices are subconsciously associated with the regular dopamine-drips most of us have grown accustomed to; physical books take you into a different realm and cast off avenues for distraction. My daughter commented that she enjoys reading physical copies because she views them as a form of a gift by the author, complete with design, type-face, weight, and feel of the pages. She experiences this as an opening, a portal to the story that does not exist with devices.

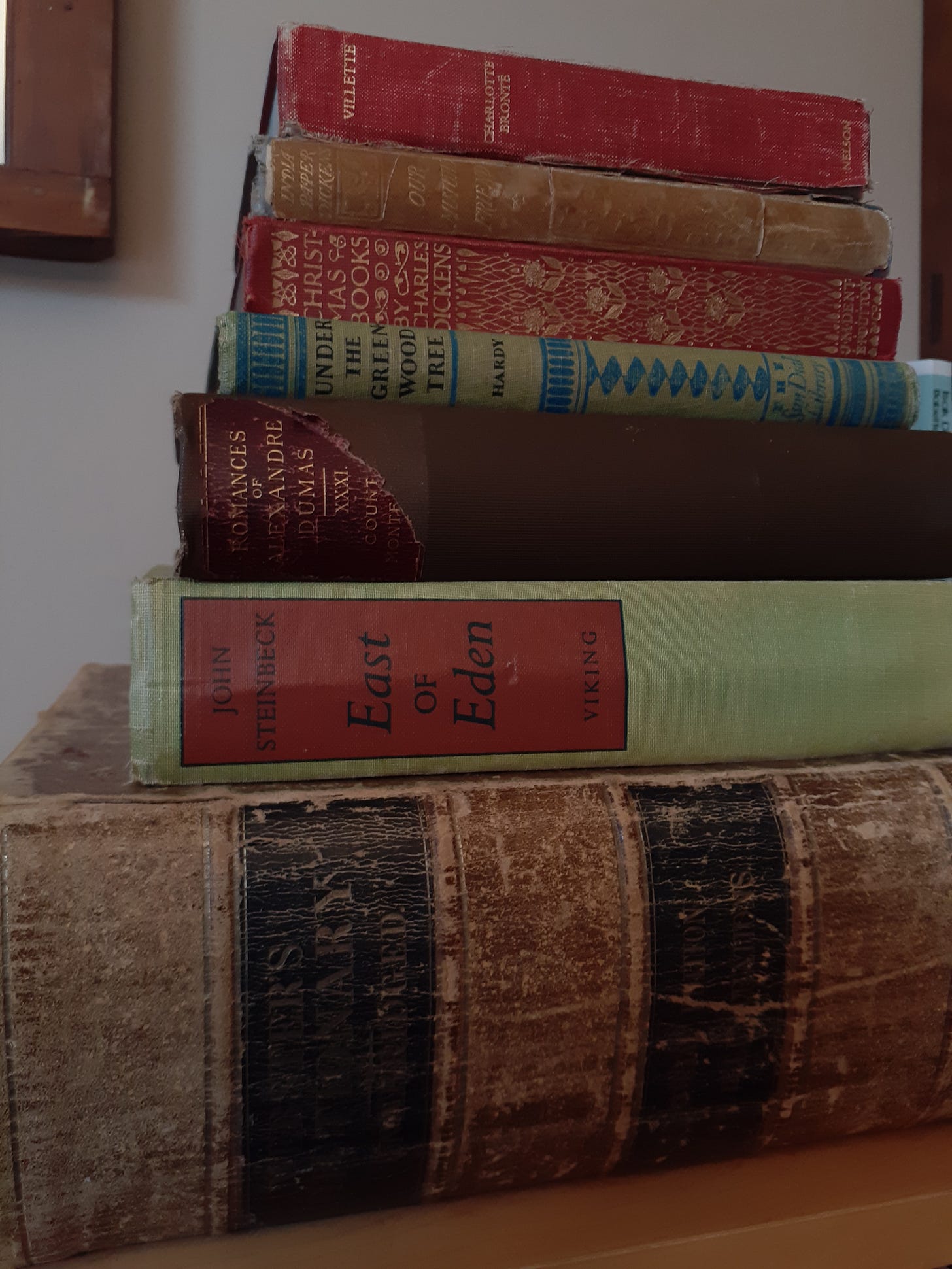

Also, to me, the feel and beauty of tangible books is simply irresistible. Here are some of my favourites:

Read old books

Getting started on reading any book is the main goal, but the ideal is to work toward reading classic books. In the God in the Dock collection of essays, C.S. Lewis explains why reading old books is of particular importance:

“…if he must read only the new or only the old, I would advise him to read the old. And I would give him this advice precisely because he is an amateur and therefore much less protected than the expert against the dangers of an exclusive contemporary diet. A new book is still on its trial and the amateur is not in a position to judge it…. “If you join at eleven o’clock a conversation which began at eight you will often not see the real bearing of what is said.”

Classics differ especially in the attention that they demand from their readers. Deep reading of dense, complex prose is demanding, but provides rich rewards cognitively, aesthetically, and emotionally. Classics also provide a measuring stick for the depth, language, and complexity that makes a book worthwhile. This is in stark contrast to modern books, which are often filled with twaddle1.

Where can parents get started if their child shows no interest in classics?

Lead by example. By putting away a device or turning off Netflix and instead picking up a book, you set a tone to be followed.

Have a regular quiet time in the afternoon where everyone reads. We have done this since our first child was born and still continue with this practice over 17 years later.

Make books available in the home. I always have been fond of being surrounded by books and we thus have 17 bookshelves throughout our home including in all bedrooms, the living room, and the library.

If the reading level seems to complex for your child, try Classic Starts which provide a simplified version of the story.

Use Librivox and allow the child to listen to the story (while maybe reading along).

Read aloud to your child. When the kids were little we used to start our mornings on the couch, reading through a pile of classic picture books before breakfast. When they were older we would do read-aloud time of longer classics in the afternoons and evenings.

If you are interested in introducing your child to Charles Dickens, I created a Classic Learner’s Edition of A Christmas Carol which includes the unabridged original text, a 40 min. read-aloud version, deep and varied classical vocabulary study, and Victorian parlour games.

It is a good rule, after reading a new book, never to allow yourself another new one till you have read an old one in between. If that is too much for you, you should at least read one old one to every three new ones.

C.S. Lewis

Get familiar with classic vocabulary

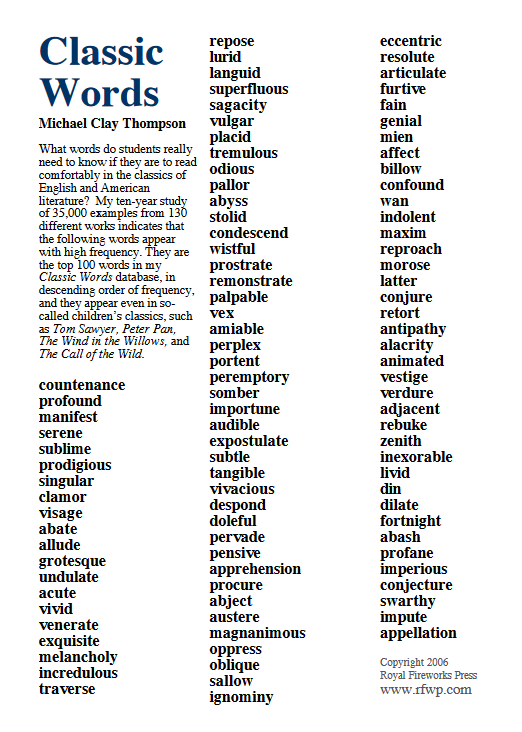

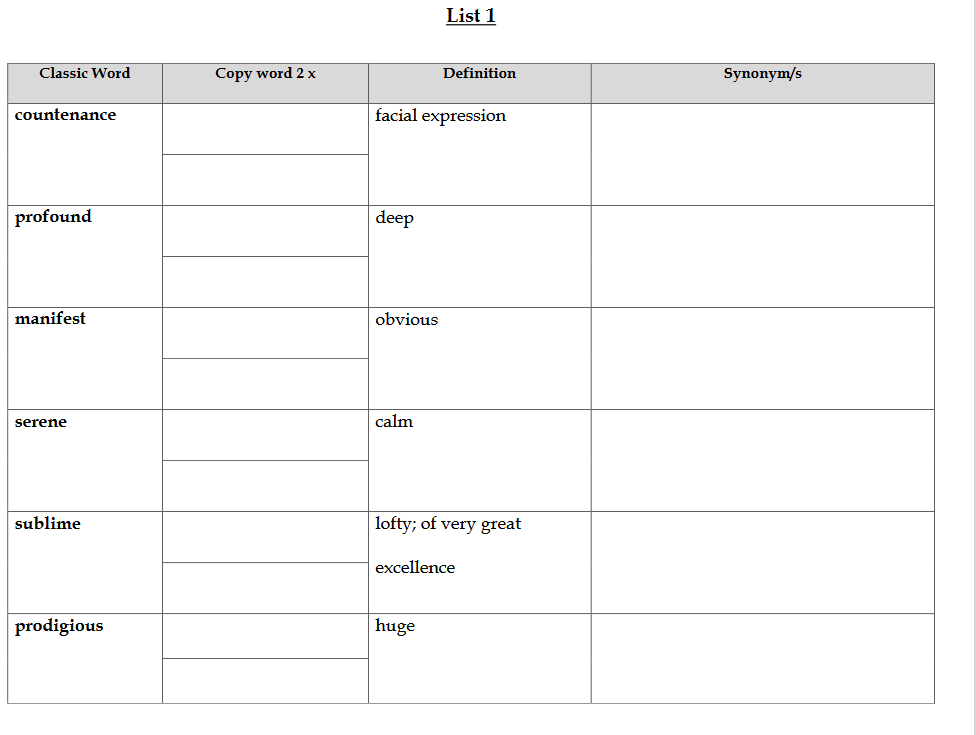

When embarking on the journey to read classics, many readers feel daunted by the complexity of advanced vocabulary richly peppered throughout older books. As a second language learner, I recall reading the Hobbit for the first time with a German-English dictionary in one hand, and the novel in the other. I thus have an appreciation for struggling through texts, and an even greater appreciation for the work by educator Michael Clay Thompson, who wondered over 20 years ago what the best words in the English language were.

As an educator who develops language arts curricula for gifted children, Thompson began marking advanced vocabulary in every English language classic that he read, a task which eventually developed into a ten-year study of 35,000 examples from 135 different works. From his research he distilled the top 100 words that appear with high frequency in classic works of English and American literature.

100-classic-words-by-MCTDownload

This list is profoundly useful and my students have often thanked me for introducing them to these essential classic words. I have developed the following worksheets that help you or your student master the top 100 classic words.

100-classic-words-with-definitions Download

Here is the list broken into 10 parts with space for you to practice

Classic-words-practiceDownload. This is what the pages look like (as a fan of cursive writing, I always leave space for copying words):

Reading lists

For Adults

If you happen to be a homeschooler2, you are most likely familiar with Susan Wise Bauer’s The Well-Trained Mind. For adults who crave a classical education that they never received, she wrote The Well-Educated Mind. It provides a guide and plan to read the “Great Books”, and allows you to “read chronologically through six types of literature: fiction; autobiography; history and politics; drama; poetry; and science and natural history.” She is an ambitious (and at times intimidating) author, and I do not suggest that you have to follow her proposed method (which includes reading each book three times - has anyone actually ever done this?), but her book lists are immensely useful and the accompanying commentary is illuminating.

The Mensa reading list for grades 9-12 is also an excellent, extensive source to get started for adults.

For Kids and Youth

Mensa Excellence in Reading Program provides wonderfully extensive reading lists students starting with kindergarten all the way to high school. The books can be read independently by the student, read aloud by the parent, or listened to as an audiobook (also, when a student completes a reading list, they receive a certificate of achievement and t-shirt). You can find the lists here:

Memoria Press Supplemental Reading List This is one of my favourite reading lists: a superb collection of books sorted according to grade/lexile levels.The recommended books for grades 3-up are in three categories: (1) classics (2) light reading (3) informational reading.

Read Aloud Revival Book Lists – These are incredibly extensive lists that encourage reading together and falling in love with books:) These lists include some classics but also contemporary book choices. Here is a selection (there are still more groups on the site):

Learning Resource Center (CLRC) Reading Lists are divided in to early elementary, late elementary, and middle school. They are not exhaustive lists but a selection of excellent books that “we have enjoyed with our own children and with many children whom we have taught over the years”. They provide a good foundation in the joy of reading and listening to stories and set the stage for the appreciation of many great classical epics in later years.

Finally there are many excellent substack writers who provide book reviews, inspiration, and guided reading groups. A few that have come to my attention are

, , , and. Also, don’t miss this post on ’s Book Clubs. Feel free to add your own shoutouts to “bookish” substacks in the comments.In the end, you will have to simply pick up a book, read, and start reclaiming your attention.

What are your reading habits3? When do you carve out time? How do you decide what to read next4? How do you help create reading habits in your children? I would love to hear your thoughts in the comments below !

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), found the vocabulary worksheets or readings lists useful, consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a ‘like’ or ‘share”.

Twaddle is to literature as a Twinkie is to nutrition; maybe tasty but would you feed it to your child as a wholesome diet? Twaddle is reading-made-easy, second-rate, stale, predictable, scrappy, weak, diluted, silly, insignificant. You get the idea.

Reading is one area where homeschoolers seem to particularly excel, reading on average two grade levels above their peers. In one U.S. study, Dr. Brian Ray utilized 15 independent testing services, to obtain information from 11,739 homeschooled students from all 50 states, Guam, and Puerto Rico, who took three well-known tests—California Achievement Test, Iowa Tests of Basic Skills, and Stanford Achievement Test. The study found that while public school students scored at the 50th percentile, homeschool students came in at the 89th percentile. Interestingly, the findings also revealed “that issues such as student gender, parents’ education level, and family income had little bearing on the results of homeschooled students.”

I generally read about three concurrent books - one at the breakfast table (non-fiction), one for the couch in the afternoon (fiction), and one to take along for appointments or while at the climbing gym with my youngest (fiction / non-fiction).

I have almost worked my way through the ‘novel’ section of The Well-Trained Mind, and I keep to a mostly classic book diet with a P.D. James palate cleanser from time to time.

Ruth, this post is a trove. Thank you for the effort you put into writing these posts (as well as including many resources throughout). I think your point about the airline passengers having no other choice but to talk, play, or read, is a good one. I also do an afternoon quiet time with my 4, 5, and 7 year olds. Each is in his own space and there aren't electronics to use. My children often page through books at this time but only (I'm convinced) after they have gone through the tedium of boredom - exhausting splashy alternatives. So I can see the benefit of having no choice but to read. That sort of controlled environment is hard to replicate in the world outside our home, but hopefully my kids are experiencing the reward that deep attention brings and will develop muscles in that area. That way when they are bombarded with stimuli and device temptation, they'll at least have the habit of attention to return to. I also second how helpful Susan Wise Bauer's work is and how the curated lists online make it easier to just start reading. Thanks again for your work here!

As busy and successful real estate agents at the time, we had no plan at all to homeschool our 2 daughters. Yet, grace of God, we did and it was His promptings that did it. I remember very well watching my wife and daughters curled up in the fat leather chair working thru the books in the Five in a Row plan, and then later into the Robinson cirriculum. That started a love affair that remains to this day with books in our home. It is worth any price, no excuses about being busy or growing a business, to gift this to our children. Your essays (and Peco's) are a welcome exhortation, and a spiritual gift of your own. Thanks!