The Critical Reality Window: How to be a default shifter

Language opportunity, "But what do you do all day?", and overcoming horror vacui

For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, we have converted the post into an easily printable pdf file.

We live in an English-speaking country, yet English was not the first language that our children learned; instead we taught them our mother tongues, two obscure and seemingly useless languages: Swiss-German1 and Macedonian. They effortlessly learned who to speak to in what language, acquiring English via interactions with extended family members, friends, and neighbours. People marveled at their multilingual facility, yet it required no particular talent on our children’s part, just a complete commitment from us to speak our own mother tongues with them. It was effortful for us as parents, all they had to do is simply emulate us.

While obscure European dialects may not seem useful, it allowed our children to view the world through varied lenses. Words influence our capacity for thought and define our mental categories; to expand our language is to expand our ability to think. Importantly, speaking these languages fluently allowed them to understand more deeply who they were and where they came from. The fact that everyone around them spoke another language did not matter.

Over the last two decades, we have come to tacitly accept screens, devices, and the virtual world as a de facto “language of the masses”. Educators are eager to render children “tech literate” at ever earlier ages, even though the utter failure of EdTech has now been well established2. Smartphones have become so essential to “communication” that a UK survey reports that “53% of children owned a cell phone by age 7 years and by 11 years, 90% had their own phone”.

Yet amidst all this hubbub of making sure our kids keep up with the technological tsunami, we forget to teach them “reality literacy”, the most fundamental language of all. It is well known that there is a critical window for language learning during childhood. If children are not exposed to language during this period of time, they will never acquire the capacity to speak. In a similar way we would suggest that there is a “critical reality window”, during which children and youth need deep immersion in the real stuff of life. Not just the linguistic, but the social, emotional, physical, everything.

The conversation around “the rewiring of childhood” has prompted a notable shift3. Schools are responding by limiting phone use, over 99,000 parents have signed the pledge to Wait Until 8th (grade) before giving their kids smartphones, and Luddite Clubs are thriving. In a recent podcast on CNN, the interviewer noted that the pendulum has swung back, so that we now ask, “…when is the right time to give your kid a smartphone, if at all?”

A recent family tech manifesto published in First Things, suggests that we need to “direct technology toward the flourishing of the family and the human person”. We would agree with this, but would place a different emphasis:

We need to direct families toward reality, so that they can flourish. If we make that our priority, then technology will always remain secondary and never dominant.

This emphasis has always been at the core of our own approach to life, and has so many facets, it could fill a book. Today we’ll focus on three areas that we found of particular importance: language, “doing”, and overcoming horror vacui.

“Technology does not just shape the family: Given that the family is the primary unit within which basic human capacities are practiced, the patterns developed there in response to technological advances tend to radiate out across all of society.”

from Technology for the American Family by Jon Askonas & Michael Toscano

Language opportunity

A newborn has sophisticated speech perception abilities, preparing him or her to learn the sound system of any of the world’s languages. Long before children utter their first words, they listen for familiar sound patterns, watch speakers mouths and actions, and relate sounds to visible cues in their environment. This crucial language learning phase is being alarmingly ruptured by the presence of screens in their environment.

A study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (Jama) Pediatrics, tracked over 220 Australian families over two years and found that TVs and phone screens interfered significantly with children’s “language opportunities”.

A systematic review investigating parental use of mobile computing devices and the social and emotional development of children aged 10 years or younger found less engagement, harsher responses, and fewer verbal and nonverbal communications between parents and children when parents were using a mobile device…for every additional minute of screen exposure, parents and children were generally talking or vocalizing less and were engaging in fewer back-and-forth interactions.

The researchers found that the average three-year-old “was exposed to two hours and 52 minutes of screen time a day” resulting in “children being exposed to 1139 fewer adult words, 843 fewer child words, and 194 fewer conversations"- each day.

Language skills are atrophying. Missed language opportunities in the early years follow children into their formal education years where teachers have noted “language skills going backwards, both in conversation between children themselves and teachers and reading and writing skills”4.

Children need to hear your voice, look into your eyes, listen to real-life conversations. Through the absence of screens we gave our children our presence.

You don’t need to be entertaining or educational; this is not about creating a constant stream of teachable moments. It is simply about being ready to interact, converse, ask questions, offer words, or share smiles, and in doing so sharing with them what makes us most fundamentally human - the ability to communicate through language.

But what do you do all day?

Many years ago I was on the phone with our internet provider, who was stunned that we didn’t need “unlimited” download nor had a TV. He asked in disbelief, “But what do you do all day?” Sometimes it is hard, especially for parents, to imagine what they would do with their kids all day, if they did not have screens to occupy them5.

Yet, it is screens that are the limiting factor; the possibilities for engagement in physical reality are endless.

When growing up our kids spent hours daily on our local playground, climbing and jumping off structures, building forts and paths in a nearby tree lot. Sometimes people who observed them would ask if they were part of a circus or a gymnastics group. “No,” we answered, “we simply let them play”.

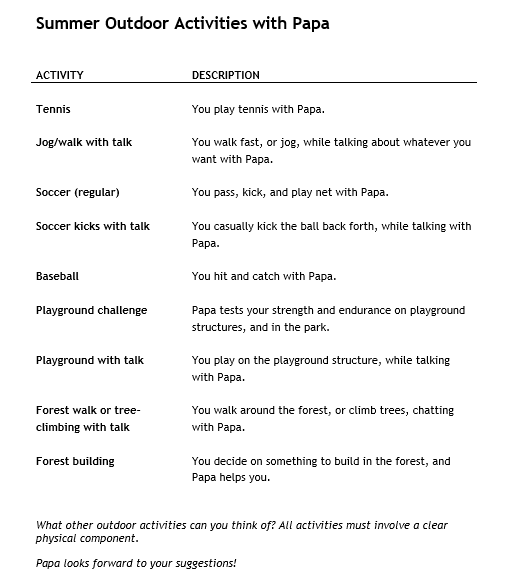

In addition to free play,

spent deliberate time playing alongside with the kids when they were around kindergarten age. One summer, he created this list of ideas that the kids could choose from:In Stolen Focus,

reports that,For years, scientists have been discovering a broad body of evidence showing that when people run around —or engage in any form of excercise—their ability to pay attention improves…[Joel Nigg] explains that “for developing children, aerobic exercise expands the growth of brain connections, the frontal cortex, and the brain chemicals that support self-regulation and executive functioning.” Exercise causes changes that “make the brain grow more and get more efficient.

Play is simple and it is free. Yet, many kids are missing out on this fundamental part of being a kid. According to this study, elementary-age children use entertainment technology an average 7.5 hours per day, time not spent playing and interacting in the physical world. It is thus sadly not a surprise to read what

encountered on her visit to an elementary school classroom:“Everything in the classroom was designed to accommodate kids with gross and fine motor sensory deficiencies. Kathy explained these tools are necessary to accomplish the catch-up work needed to build kids’ core strength. There were floor surfers so kids could slide on their bellies across the room, vestibular wedges, a balance disk, and more.“This is the regular classroom. This is standard for our younger students,” the teacher said.” The classroom was not equipped with tables and chairs, but rather hammocks and big balls; the teacher further explained, “Since kids spend so much time indoors on screens, they are entering school lacking the core physical strength to help them sit in a chair and learn.”

Children are literally losing touch with physical reality. Many young kids are adept at swiping and tapping screens but are lacking fine and gross motor skills. They move blocks and shapes on tablets, but lack the experience of joy in building towers—and they lack the frustration too.

Those frustrations of building towers that fall over and again are important. They help to develop emotional regulation, build resilience, and over time, result in mastery of skills.

Drawing and handwriting, rather than typing or swiping on a screen, are more conducive to learning because they activate “neural processes related to memory and cognitive effort.” (see Ose Askvik, 2020).

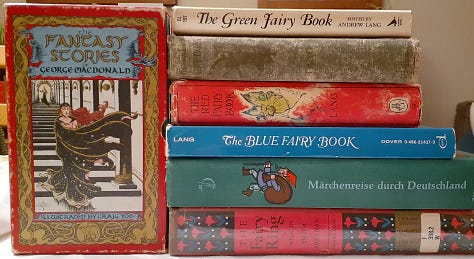

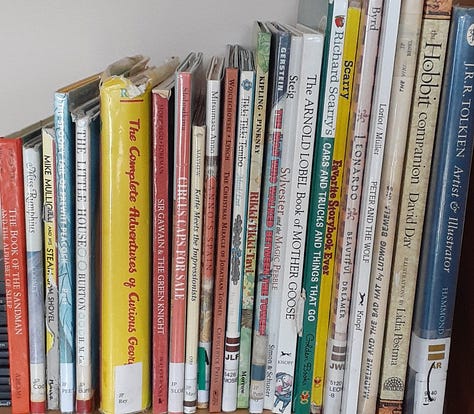

Apart from playing outside, building, and creating, we spent an immense amount of time reading and looking at physical books. When our children were younger, one of my favourite parts of the day was our early morning reading time on the couch. We would pile together with a stack of picture books on the coffee table in front of us and work our way through.

Physical books, apart from simply being more beautiful and pleasant to the touch, have a vastly different effect on reading than text on screen.

summarizes just some of the findings in her article here:One study published last year suggests that cognitive engagement is higher in children when reading printed books versus digital media. Another such study in 2018 found that there was higher functional connectivity in the brain when reading from print versus a decrease while reading from a screen. And yet another research review highlights, “Paper-based reading yields better comprehension outcomes than digital-based reading.”

Also, we walked, lots. No matter the weather, no matter where we were, be it monochrome Canadian suburban sidewalks, nature paths, mountain trails, or interesting European city streets, walking was part of our day.

Our children are now aged twelve to nineteen. Our daughter got her first phone when she entered university at age sixteen. She uses it mainly for arranging plans, music, and podcasts. Our sixteen-year old son has never had a phone, not even a flip phone. He does not want one. He calls his friends on our landline (he even memorized all their phone numbers by heart), and that is how they reach him6. Our youngest, almost thirteen, has never even thought about having or needing a smartphone.

Engaging with physical reality around them, allowed our children to grow up as active creators, rather than passive consumers expecting to be entertained. It has left them with curiosity and wonder, an interest in people and conversations. Importantly, they had the opportunity to develop deep and sustained attention, a capacity that remains elusive for many age mates.

Overcoming horror vacui

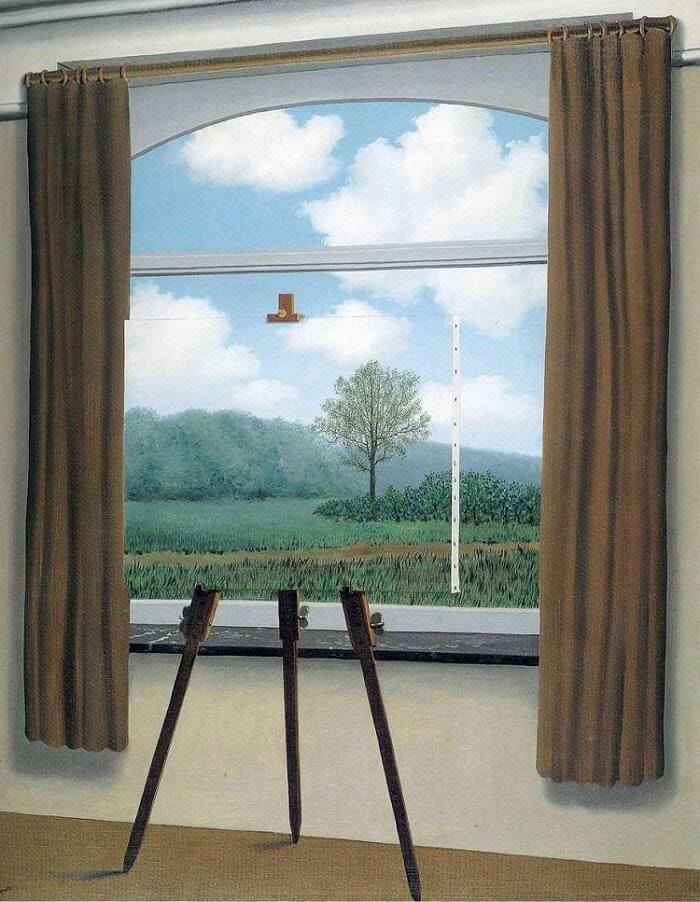

A couple of years ago I related in a post how we were on a transatlantic flight from Switzerland back to Canada, when the passengers discovered, to the horror of most, that there were no screens and no plugs to charge phones:

After the first gasps of surprise and dismay (especially of parents with small children) subsided, a wonderful scene unfolded. I had no idea so many people still read books! The photo below is the view across the row from me. The plane was humming with conversation; two men behind me who had never met before, struck up a conversation (a joy to listen to Scottish accents) and shared beers and stories, children played paper games, and our family rotated through reading Thomas Hardy, Seinfeld scripts, Ian McEwan, C.S. Lewis, and Calvin and Hobbes (something for every age and interest). It seemed like a flight in a time machine, where people still remembered how to converse, play, read books, and spend time away from black mirrors.

Parents have been shaped by media images of children who are not only constantly entertained, but always on the verge of excitement. Every moment needs to “pop”, offering thrills or new adventures. We are led to believe that it is not only our task to keep our children engaged, but to ensure that we have a mountain of gadgets, developmental toys, and programs to help them excel.

In The Anxious Generation, Jonathan Haidt discusses how, as parents became increasingly isolated from “local wisdom” and more reliant on “experts”, they “began to think like carpenters who have a clear idea in mind of what they are trying to achieve”. Raising children has become about producing a “superior product”.

And in a consumer-oriented society this means we need to buy things, experiences, and entertainment. Every moment needs to be filled; all empty time is a potential waste. Silence is absent. Boredom is to be feared. We have developed full-blown horror vacui7, drowning our kids (and ourselves) with images, apps, games, and entertainment.

Worst of all horror vacui results in a loss of self-discovery. Children do not have the time to reflect on what they actually enjoy thinking, doing, pursuing, creating.

Children need silence to think. They need time to simply lie on the couch and reflect. They don’t have to be entertained with movies while driving, but can stare out the window and simply wonder.

“How do you find meaning when your day is filled, from seven in the morning to nine at night when you go to bed, with somebody else’s idea of what is important?…If you don’t have any free time to figure out what [emotionally] turns you on, I’m not sure you’re going to find meaning. You’re not given time to find any meaning.”

speaking withYou are the most potent default shifter

It is commonplace to hear children from the age of eight through the teen years describe the frustration of trying to get the attention of their multitasking parents. Now these same children are insecure about having each other’s attention.

— Sherry Turkle, Alone Together

If our goal is foster a “critical reality window” for our children, the most difficult task is shifting our own default. Children, and even babies, watch our every move. Children truly do make us better people, because they hold us continuously accountable. We see ourselves mirrored in their behaviour, and it is a humbling experience. They can smell hypocrisy keener than freshly baked cookies.

They observe what we pay attention to, they note what objects we hold dear, and they will long to mirror every move we make.

We have a lot of books in our home (over 3000 on 17 bookshelves according to our youngest son’s estimate). It is thus no surprise that our daughter would fill her little backpack with books and carry it with her wherever she went. Peco has been a writer ever since he can remember, and watching him write away in countless notebooks, the kids would start scribbling their own “stories” even before they could write.

We created a “home made for humans”.

No matter whether people around you choose to blindly embrace new technologies, no matter if all of society seems to be living life virtually, you have tremendous power in setting a different default for your family. It may feel challenging, but you would be surprised how many people no longer raise their eyebrows at our decisions, instead resonating deeply with the need to offer children a firm foothold in reality.

This reality default shift was captured perfectly in my conversation with former social media influencer

:Truth be told, I am wildly surprised by how little resistance there was. Ruth, I have never been more convinced that people are so very weary of this world we’ve built, now more than ever.

In the early days of our opt-out lifestyle, there were only a few raised eyebrows, and those were mostly rooted in challenging our commitment to raise children without personal devices. There seems to be an argument that if we limit technology in our household, our children won’t know how to balance a digital lifestyle once they’ve moved on from our household and are out in the world. (Worth noting: one conversation with my local zookeeper about how their resident chimpanzees are using iPads blew that argument to bits for me.) But truthfully, I’m of the school of thought that I’d rather teach my children to build a healthy foundation of habits to return to when the world feels dysregulating, rather than begin the dysregulation process for the sake of a premature learning opportunity.

And I think I’m not alone in that, and if I ever was, I am no longer. We are so blessed to have such massive amounts of research at our disposal regarding what these devices are doing to our minds, and certainly the minds of our children. So now, when the raised eyebrows come my way, I find that people are no longer asking: “Why opt out?” Instead, they are asking, “How?”8

We are fortunate that we could foster a “reality default” for our children. Depending on one’s circumstances, there can be many challenges to shifting toward a digitally minimal lifestyle.

The important thing to remember is, that we do not need to start with a fear of technology or its effects on us and our children, but rather a positive motivation to connect with the real. More people than ever are starting to question our society’s technocentricity, and many youth are starting to sense that much of it is a sham.

Don’t settle for an image. Be a default shifter — the real is within your reach.

Making a default shift is challenging, especially when you are doing it alone. We want to support you!

During the past two years we have led a Communal Digital Fast coinciding with Lent. We would love for you to join us again this year, starting on March 3rd. Stay tuned for details!

We would much prefer to discuss all these thoughts with you at our kitchen table over a cup of coffee. The next best thing would be for you to let us know that you are there — we’d love to hear from you:

Share your reflections in the comments, share the post with your friends, or simply give a like. If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), please consider supporting our work by becoming a paid subscriber.

What is the “default” in your home?

What is working for your family; what is a challenge?

What would you like to change about your family’s technology use?

Please share your questions and experiences in the comments!

If the ideas Peco and I write about resonate with you, why not consider joining us for a most extraordinary extended conversation? We will be leading an 11-day Camino Pilgrimage in Spain this June, and would love for you to join us as we walk, converse, share meals, visit historic sites, build relationships, all while hiking through a naturally and spiritually inspiring landscape.

If this sounds intriguing and you’d like to learn more, join our live meeting for the “Camino Curious” this Sunday, February 16th, at 2PM EST.

For more details see this post, download the brochure, or register directly here.

Further Reading and Listening

A Future for the Family: A New Technology Agenda for the Right in First Things by Michael Toscano,

, , , and Emma Waters. Signatories include , , , Christine Rosen, and others.Technology for the American Family in National Affairs by

and Michael ToscanoDo Young People Need Smartphones? A Parent and Teen Weigh In. Clare Duffy interviews Mark SooHoo (Wait Until 8th) and Jameson Butler (co-founder of the Luddite Club) on her podcast Terms of Service.

Why The Humanities Are Essential For Digital Literacy by

The Learning Paradox of Ed Tech & AI by

and Cris Rowan. One resource mentioned in this article is a superb 100 page evidence-based research summary on “the impact of technology on human development, behaviour, and productivity.”Kids, Smartphone, and Social Media Resource Kit by

“I want to build a cockpit” boy, 12, tells his parents - our youngest son’s story featured on

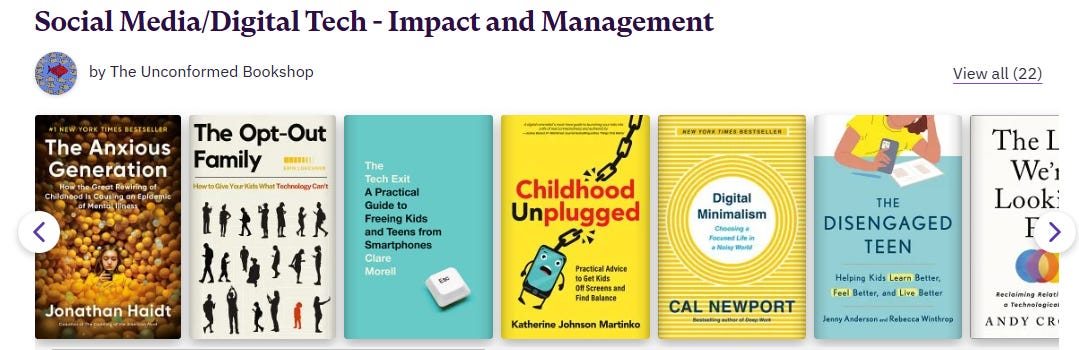

’s LetGrow blog.Books

You can find a compendium of helpful books on family and technology in our Unconformed Bookshop. I particularly look forward to

’s The Tech Exit (to be released in June). I also highly recommend Jonathan Haidt’s The Anxious Generation, Erin Loechner’s The Opt-Out Family, and ’s Childhood Unplugged.You can find all these titles here, from your favorite bookseller, or at the library.

A spoken dialect that varies across the 26 Swiss cantons. Similar to German, but different in grammar, pronunciation, and with some variation in vocabulary. Germans will often comment, “I know what you are talking about, but I don’t know what you are saying.”

See here: “An analysis of 2009, 2012, 2015 and 2018 PISA scores validated what we’ve known for some time – the more we use technology in schools, the less likely students are to learn.”

We also cannot simply blame the covid-fallout as teachers have observed these trends “at least five or six years pre-Covid”.

When our children were younger, they had no screen time at all. As they got a bit older, starting at around age 5, we would have a common movie evening on the weekends. Us as parents kept to the same diet. We still keep the weekend film rule, which allows for a rhythm to the week, rather than expecting passive entertainment on a daily basis. We have various rules about computer time and type of use (ranging from none for our 12-year old to self-directed use for our 18-year old).

Our teenaged son has this to add: I am 16 and don't have a phone, I do not intend on getting one. I have seen too many of my friends' lives go down the tube once they got a phone. It almost always starts with the same innocent excuse: “I’ll only use it to text my friends and call my parents.” Even though it may begin as this, eventually it will move to almost continuous browsing on social media and the internet. For teens who want a phone solely because all their friends have one, I have this to say: if a friend group relies on you to have a phone, that's no friend group. My advice is, find people who are like you, in real life, not online.

Recently our daughter, who is currently taking a course in Roman Art History, brought to our attention the artistic method of horror vacui (literally the fear of empty space) employed by Etruscan artists who would fill all empty space with decorations, garlands, animals, and figures.

Erin offers some helpful, practical starting points for families who feel overwhelmed by their tech usage and desires to scale back at the end of this post:

I start to sound like a maniac out in the public because I try to spread this idea to every parent I talk to and I constantly get the same excuses about why they gave into dolling out cell phones to their children.

Granted, my son is only 12 now but in middle-school, he estimates that 90% of his classmates have cell phones, and on any break, are head-down into a video game like Brawlstars or some other flashy mind-numbing addictive attraction. He says he thinks all of the girls have them and are constantly on social apps (don't get me started about that).

However, he impresses me so much with his resistance to this trend. He personally petitioned the school and started a Rubix Cubing club, he plays D&D or Chess on his breaks, and even tries to encourage his friends to put down the phones and join in.

This fight was not intuitive because you need to be very aware that it's a problem... and we all got suckered into it ourselves when this novel technology caught our eye. Modelling is key and through a lot of conscious self-discipline and many talks with like-minded families like Peco's, I feel like the process is having very positive effects on our family as a whole, not just the children.

Again, I would like to thank you, Peco and Ruth, for your hard work on this topic. It is a life-saving endeavor.

Yes to all of this!

I've come to appreciate the phrase 'the language of the forest', as a way of describing a comprehensive sense of how a natural ecosystem (around here, it's mostly woods) works that comes with sustained contact. I learned the language of the forest for Northern New England though intense effort across a decade of my early adult life. My kids, thanks be to God, are learning it as a native tongue. I'm thrilled when I see our four year old teaching the two year old about which plants are good for medicine, or which tree species are better for carving, as she's already developed pattern recognition for dozens of species. She'll never remember not knowing this. Unfortunately, we don't have proficiency in any other spoken languages in our home, but we can give our children immersion in the 'language of the forest' during the window of early language acquisition...