High Fidelity: Bringing back commitment culture

"Post-meh-dernity", the mind's braking system, and training for high fidelity

For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, we have converted the post into an easily printable pdf file.

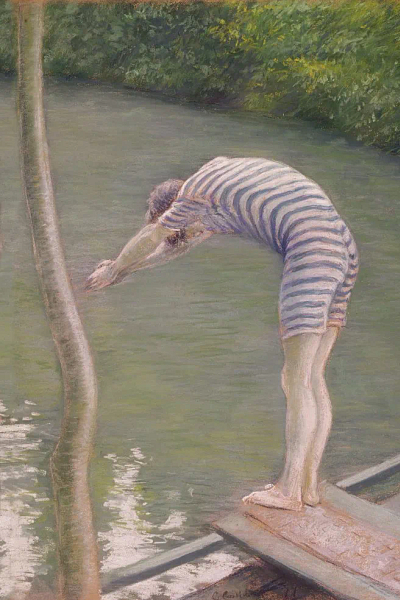

Spot the common thread:

1. Two young, vibrant, intelligent women were visiting at a friend’s house. They both had well-paying jobs at a tech firm and were adamant that they were not interested in marriage or having kids. “I can’t even take care of my house plant; what could I possibly want with kids?” They said that most of their co-workers had no interest in marriage, and many considered life to be “over” by age 30.

2. Lilly Philips sleeps with 100 men in a day, and is aiming to “break the world record” by bedding 1000 men in a 24-hour period.1

3.

relates in this note how she set up a meeting for a museum tour for 12 families (even obtaining a grant to cover admission). The day before the event, 11 families had cancelled. Dixie’s family was the only one left, “NO ONE kept their commitment”.2You could likely add to the list above with examples from your own experience. We visited an octogenarian relative this weekend who plainly stated, “Oh, you can’t trust people anymore”. Why do we find it so hard to commit to just one person, or even to show up at an event when we said we would?

Commitment means saying yes to one choice, but it also means a definite no to the alternatives, which is what makes it so hard. One door is opened, but all the others are closed.

No is not a popular word. It sparks disappointment and makes us wonder what we’re missing out on. It’s always been hard to say no, but it’s even harder in a society that wants to say yes to everything. Ideally, we would let our yes be yes and our no be no, but instead we default to, Sure, okay, maybe, well why not—um, wait a minute.

And it’s no wonder, because our options are infinite. Each minute Snapchat users share 527,760 photos, and in that same minute there are 990,000 Tinder swipes and 4,146,600 views on YouTube. Even if we’re offline, we’re faced with myriad choices on store shelves or see ads on countless billboards. Buy this, buy that—why not?

Consumer culture is premised on Why not? Why not try this skin cream, these vitamins, this food, this dazzling new experience of whatever? After all, you might like it. The internet works by the same teasing principle, inviting us to digitally taste, touch, sniff whatever shows up six inches in front of our eyeballs. Maybe we like it and maybe we don’t and move on to the next click. Either way what is being cultivated is neither a committed yes nor a committed no, but a mindset that is endlessly open to a potentially better option. We’ve always got one foot out the door.

It's gotten so bad in relationships that even parents are concerned when their adult children choose to say “yes”. As

observes:It’s funny because I was talking to a friend recently about how if you get engaged young now, or do anything that signals actual commitment, that’s when family and friends worry for you. It’s like some parents are protective only when it comes to commitment. They worry about you closing down options. A few of my friends, young women in their mid-20s, made commitments recently—they got engaged, for example—and their parents panicked.

Whether in relationships or other areas of life, a degree of openness isn’t a bad thing. We naturally want to scan the landscape and see what’s out there. Openness, curiosity and exploration are an essential part of what it means to be human. But as we devote more and more time trying out new experiences, whether digital or non-digital, the mental muscles that might otherwise become strong enough to offer a definite no or a definite yes begin to atrophy. Like junk food gluttons, we want stimulus more than commitment, even though, with time, our taste buds grow dull, our cognitive bellies start to hang out, and everything starts to get a bit meh.

In a crowded marketplace of choices, even truly good choices can take on a meh flavor, as is illustrated perfectly in this video that our daughter shared with us:

The rise of “post-meh-dernism”

Large territories of Western culture have been captured by postmodernism. Postmodernism is a complex philosophy, yet it boils down to the idea that there is no objective truth. Which makes it hard to commit ourselves to anything, since everything is uncertain. Of course, for those who have been trapped in a rigid or destructive worldview, postmodernism can feel like liberation, freeing us from whatever power oppresses us, whether Church, Family, or Those Bad People (whoever they happen to be). But after the cheers of liberation are over, after objective truth is forgotten and all the options for life have been explored and discarded—since none can be true—we arrive at meh.

Postmodernism is post-meh-dernism. It starts by offering freedom and excitement, and ends by breeding apathy.

And this is the cycle in which many of us find ourselves. In a highly consumer and digital culture, we get excited only to end up bored or indifferent. This chronic feeling of meh flattens out our motivations, turns our values into yogurt and leaves us with nothing solid to hold onto, nothing to really believe in, except more consumer choices and options. It kills God, not by killing God, but with a shrug. It is the world that ends not with a bang but a whimper.

In my younger days I (Peco) used to spend a lot of time meditating, not just as a form of mental hygiene, but with a wish to transcend the ordinary world and attain spiritual enlightenment. I was zealously practicing a form of meditation that required me to empty my mind completely, until one day a question occurred to me: “Why do I have a mind at all?” If there was a spiritual reality behind everything, why would I be given a brain which possesses the powers of language, reasoning, memory, and other wondrous faculties? Either the universe was under the control of a mischievous deity, or else there was some purpose to the brain in all its complexity.

The mind and its braking system

The last part of the human brain to develop is the prefrontal cortex. It’s right behind the forehead, and it isn’t fully mature until around the mid-to-late 20s. This part of the brain is associated with some of the things that make us most human, like our personality, our ability to be socially appropriate, and problem-solving, to name but a few. It’s also heavily involved in our ability to inhibit and control our behavior. If the brain was a car, then the prefrontal cortex is the driver in heavy traffic, at times braking, at times signaling, at times turning, at times accelerating, always anticipating the next move—or to put it more simply, saying yes to one thing and no to another. The capacity for a decisive yes and no is built right into one of the most sophisticated parts of the brain.

If we place the brain in the context of a human life, and that life in the context of a society, it isn’t a stretch to suggest that developing a healthy, committed capacity for yes and no isn’t just important for driving or isolated mental tasks. It helps to sustain what it means to be human through a moment-by-moment self-control that keeps us faithful parents, faithful friends, faithful fighters for a good cause. Unless, that is, we adopt a philosophy or lifestyle that is chronically disinhibited, hedonistic, or non-committed.

There is a beautiful power in a committed no. When we rule out one course of action, two things happen. One is that certain doors are shut, locked, the keys dropped in the ocean. The other is that we activate our energies around an alternative pathway. To say no is not simply to deny something, not just an absence and dead end, but a moment of mental combustion that can explode energy into a new direction. A committed no is the launch pad for a committed yes.

Years ago, with little money and a new baby, we made a risky commitment: we would move in with my mother, who lived in a modest 1400 sq foot townhome. That commitment lasted fifteen years. In a previous essay Ruth described it like this:

For most of those years, our three children (then aged 8 to 14) shared the same, small 10’ by 13’ bedroom. In a world where every individual is assumed to have the right to a private room, puzzling three children into a tiny space with bunk and loft beds, bookshelves, and clothes cubbies was not only an anomaly, but struck some friends and family as simply undoable. While there were plenty of challenging moments, especially during arguments (“Well, I am going to my room!” followed by “Oh yeah? Me too!”), the constraints of the environment produced a strong and lasting bond between the siblings. The smallness of the space forced them to learn tolerance, compromise, and self-denial, accompanied by a depth of camaraderie that fewer and fewer siblings experience. Their environment forged their interactions and the depth of their connection.

In heavy traffic, our foot hovers over the brake pedal of the vehicle, to slam down on it, if necessary, to prevent a crash. In relationships, the inhibitory centers of our brain hover over the brake pedal of the heart, to slam down if necessary in the event of impulsive emotions and rash behaviors. Our ability to say no, again and again, is what allows us to say yes to the things we really want—whether a safe journey in a car, or healthy relationships within a family.

Family is a good, if obvious, example of the power of commitment. What about our relationship to technology? Many Amish and Old Order Mennonites don’t have their homes connected to the electrical grid. That means no TV, at the very least. No TV means no daily exposure to graphic violence, sex, commercials, or endless imaginings about other “options”—in other words, no exposure to all the things that might have made their lives seem bland and unhappy by comparison.

As Barry Schwartz points out in his 2004 book The Paradox of Choice, the depression rate among the Amish of Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, “is less than 20 percent the national rate.” Their social ties are extremely strong, but because they have vastly different expectations about personal autonomy than mainstream Americans, they don’t experience their communal responsibilities as personal sacrifice.

And the commitment of many Amish and Old Order Mennonites not to be on the power grid—which was historically decided on long before the internet age—meant that when that age finally arrived, it didn’t impact them the way it impacted us.

The high fidelity life

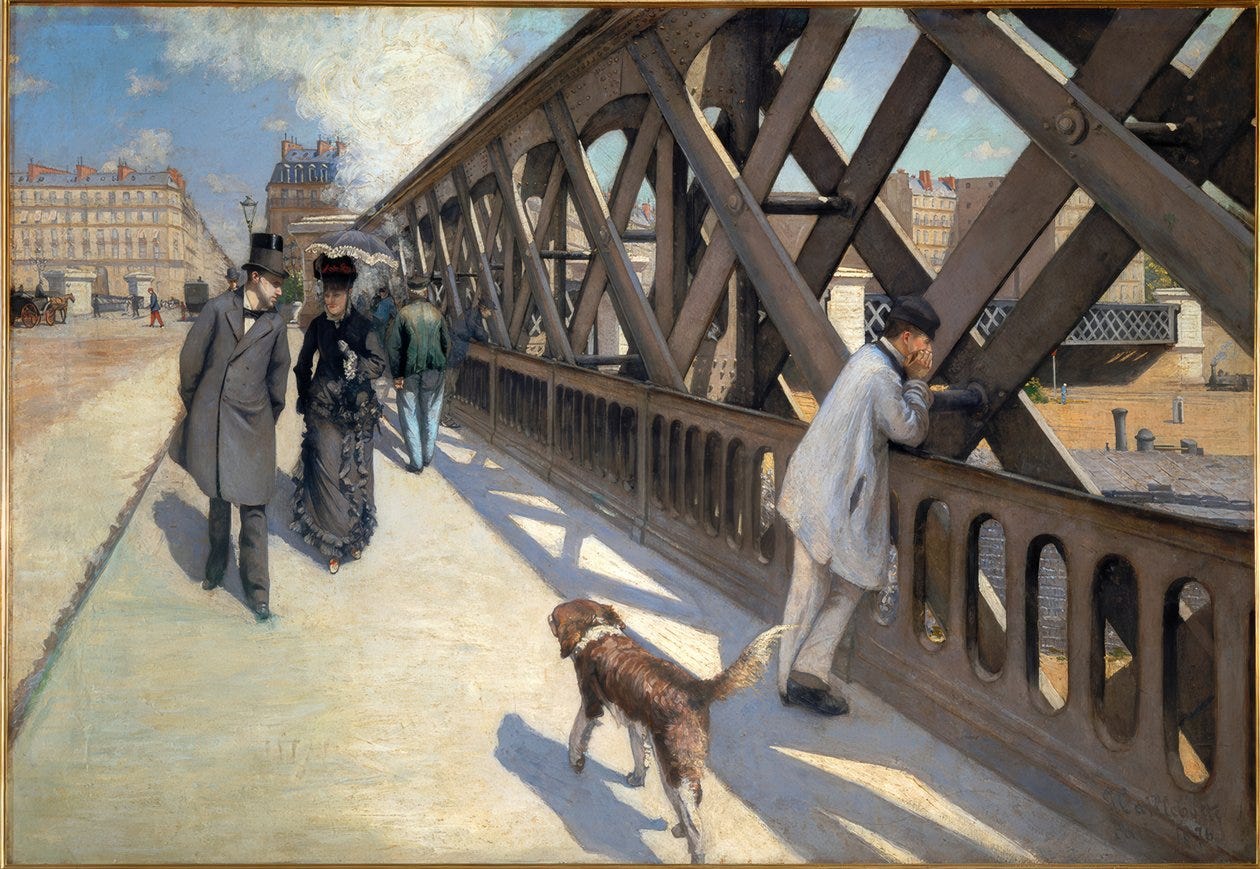

The commitments we make as a society run through us like iron girders in a building. We often take them for granted, forgetting they hold the superstructure together. Iron girders might seem boring, but they’re what make the building possible; the stability of the walls, the windows with the lovely views, the rooms that shelter us and where life unfolds in all its varieties.

Many of our basic commitment girders have been weakened by a culture of entertainment, TV, consumerism, and choice overload, and most recently by the internet. Of these, the internet is arguably the most powerful, and the most tangible manifestation of postmodern philosophy. While postmodernism simply questions truth and proposes the uncertainty of multiple perspectives, the internet actually gives us these perspectives in our daily experience.

For every viewpoint we can find on the internet, we can often find a diametrically opposed viewpoint and a thousand variations in-between. The problem isn’t so much that there are multiple perspectives, but that we spend hours each day scrolling through options and possibilities, each of which is like a hammer, gently knocking out the rivets in our heads. The girders loosen, and our entire view of the world gets wobbly and uncertain, and we don’t feel safe unless we keep everything at a distance. The internet cultivates commitment hesitancy. We’re afraid to give a definite yes, not even knowing why, but just sensing it’s too heavy, too much to bear. “Learning to choose is hard,” according to Barry Schwartz. But “learning to choose well is harder. And learning to choose well in a world of unlimited possibilities is harder still, perhaps too hard.”

The internet has accomplished something that postmodernism, as a philosophy alone, could never have accomplished. It has created a global wrecking ball for smashing all “true” beliefs about life. Well, all beliefs except for one, of course: that there is no truth. Never mind that that’s an absurd paradox.

If it feels like our culture is falling into a void, imploding into itself, a major part of this implosion is the work of the postmodern wrecking ball, busying itself with turning the good, the beautiful and the true into rubble. In the end, the only remaining “good” will be that, given enough time, the wrecking machine must eventually slam the demolition ball into itself.

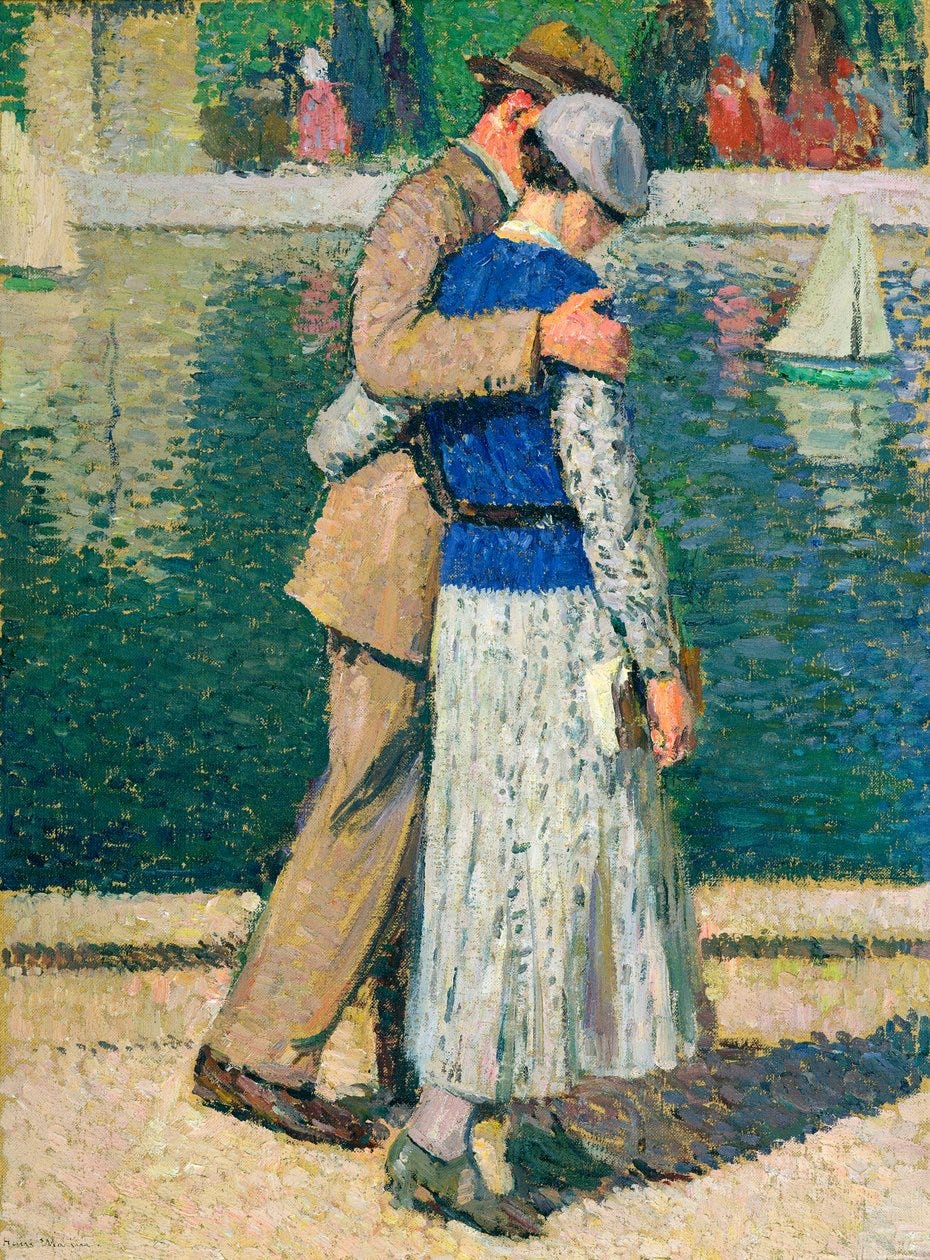

There is a deep connection between truth and commitment. It’s hard to be committed to anyone or anything unless we trust in the truth of our ideas and values about the vital matters in life—especially love, relationships, purpose, and vocation. And even if we are sure about ourselves in these areas, we still might not be able to commit in some situations, because other people might still be caught in a fog of postmodern relativism, unable to choose decisively for themselves.

If many young people today seem oddly lacking in motivation, or so hesitant and uncertain about commitments like marriage and children, a part of the reason is that their capacity for seeing truth has been undermined by postmodernism and its most potent manifestation, the internet. When nothing is certain, it’s perfectly logical to remain non-committed. Got to keep every door open—because you wouldn’t want to miss out.

And you wouldn’t want to be abandoned either. As Freya India points out:

…I think this is a major and often missing explanation for falling marriage and birth rates—maybe it’s not selfishness, maybe it’s not narcissism, maybe deep down at the heart of it, we are terrified someone will walk out. That they will decide, one day, to give up. That even if we gave it our all, it would never be good enough. We simply don’t believe anyone will stay.

And so our commitments remain chronically fuzzy, and the choices we make are marred by fuzziness and haunted by the inevitable meh and fickle fantasies about a better option. If we were sound systems, our experience would be “low” fidelity—distorted and hollow—when what we really want is the opposite, a full and vibrant high fidelity3 life. We want actual love, not a hundred shallow partners. We want a sense of purpose not self-doubt, motivation not apathy—and for those inclined to the spiritual, a faith we can trust, not simply endless searching or symbolic sentiment.

If we want to recover a higher fidelity life, we might begin by rejecting the major sources of distortion. We can turn away from worldviews like postmodernism that uphold uncertainty as a basis for living, and we can also limit activities, consumer or digital, that create choice overload or mess around with our mind’s control systems. Most of all, we can decide that a reasonable degree of truth about love and life is actually possible.

A belief in truth is necessary for commitment, though it comes with the risk of stubbornness, or turning out to be wrong, or a fundamentalist insistence on being right. The cure for all these is not the pursuit of uncertainty, but the pursuit of humility. Yet despite the risks, to be human is to seek truth and the commitments that arise from it—to seek these commitments, to live by them, and if need be, to die by them.

Training for high fidelity

Reflecting on our own marriage and life experience, here are some simple starting points that we believe form fertile ground for healthy commitments:

Seek truth in matters in faith, love, purpose, and life, and do so with humility.

Be truthful. Commitment requires trust, and before trust must come truth. Be honest in your relationships and daily activities. Don’t lie, even if it’s convenient or seems trivial.

Be faithful. A committed heart is not shared, but devoted. If you have been unfaithful, don’t just bury your mistake but make amends.

Practice diligence in small (and big) things. It may seem negligible to put away a shopping cart or return a library book on time, but small actions set the tracks for more important actions.

Use committed language. Avoid speaking in “whatevers”. Mean what you say, and say it clearly.

View less online content to reduce choice and comparison overload. As a starting point, join the Digital Fast during the upcoming Lenten season4 or create your own gameplan.

If you need to cancel plans, call. Don’t use text messages as a cop-out.

Spend time being in the presence of real people in your local surroundings such as libraries, community centres, cafes, churches, markets, bookstores, etc. or host a simple gathering yourself.

Form relationships with people who believe in commitment such as those in church communities.

Spend time doing real things. See Simple Acts of Sanity for an inspiring list to get you started.

Delete dating apps.5 If commitment is what you are looking for, someone scrolling past your profile is the wrong starting point.

Ask trustworthy family members for guidance6. If you are a parent, offer guidance.

Ask someone from the pre-internet generation for their perspective.7

What points would you add to this list?

What are the most important ingredients for creating “high fidelity”?

Why do you think people are avoiding commitments?

Have you experienced choice overload or commitment hesitancy?

We would much prefer to discuss all these thoughts with you at our kitchen table over a cup of coffee. The next best thing would be for you to let us know that you are there — share your reflections in the comments, share the post with your friends, or simply give a like — so that our writing feels a bit more like a conversation and less like a soliloquy.

Worthwhile Reading

and A Manifesto in Defense of Courtship by

Culture Making as Resistance by

For Gen Z, Social Media is Optional

for After Babel (Jonathan Haidt and )When is Activism Really Just Slacktivism? by

New in the Unconformed Education Section:

Would you like to connect with me (Ruth) to talk about your homeschooling questions, or simply to chat about family life? I now offer a 40-min. “one-on-one zoom chat” for annual paying subscribers. If you are interested, send me a direct message via Substack chat (simply click “message” on my profile page).

Come and join us on a Camino Pilgrimage!

We’d love to meet you in person! Why not join me, my husband Peco, and Dixie Dillon Lane on an eleven-day pilgrimage on the Camino in Spain from June 14-24? You can read all about it here or download the brochure here.We would love for you to join us in visiting historic sites, sharing meals, building relationships, all while hiking through a naturally and spiritually inspiring landscape.

See

Go Where You Are Invited “It appears we're living in a time when people don't hesitate to bail on their friends for reasons that range from justifiable to absurd.”We want to give a nod here to the movie High Fidelity based on

’s novel. We first watched it on a Tuesday (cheap night) in a small Ottawa cinema in 2000, and clearly recall all the “commitment” questions it raised in our own young lives at the time.This year’s Digital Fast will begin on Monday, March 3rd. Stay tuned for more details.

See

’s piece Casual Dating: “I deleted the apps. They weren’t doing me any good. The screentime was violating my principles, the algorithms dictating my desires, the self-commodification exacerbating some highly-specific insecurities (wouldn’t you like to know). I turned my attention to real life.”See

’s New Year’s resolution to “Bring Back the Aunties”: Now it becomes clearer why it is so often older married women who end up doing most of the arranging, facilitating, tinkering, and meddling as regards family formation. As a group, we have life experience, and more information on which to judge character and assess a good as opposed to merely showy potential mate. We have an interest in weaving social bonds: there’s nothing nicer than seeing two young people from families you know form a relationship and deepen the ties across a social group.”