Beyond Managing Screen Time: How to Make a Home for Humans

Scaffolds, Altars, and Screen-Free Living Spaces

Today I read the most recent post on

’s by psychologist and , Research-Backed Advice on Screen Policies for Young Kids. Normally I find myself nodding along in agreement to most of the work shared on After Babel, but sensed that something crucial was missing in the advice being offered.While Haidt does emphasize delay, the problem is that the article rests on the assumption that screens will inevitably be a big part of our children’s lives. It is a given that screens will interrupt our interactions (“It’s unrealistic to think that we’ll never look at our phones when around our kids”); that we need screens to cope (“Yes, sometimes the whole point of using screens is to give ourselves a break”), and that we shouldn’t care too much about screen time (“we may be better off focusing less on how much our families are using them, and more on how.”).

This is the wrong default assumption. While I agree that this is a reality for many families, I also wonder whether the advice offered fails to help families explore a different approach to screens as a whole.

Why not turn things upside down and start with a different foundation?

We need to create homes that are human-centered.

What would such a home look like?

Over a year ago1 I published How to Make a Home for Humans when the conversation around the impact of digital devices on our lives was heating up. It garnered a lot of engagement and is a fitting piece to share again to complement the momentum gained by the team at The Anxious Generation, Erin Loechner and The Opt-Out Family,

, , , and the LetGrow movement, and many more.If you are among my long-time readers, I would love to hear whether you have made any changes to your physical home environment to make it more human-centered over the last year.

How to Make a Home for Humans

That house was, as Bilbo had long ago reported, ‘a perfect house, whether you like food or sleep, or story-telling or singing, or just sitting and thinking best, or a pleasant mixture of them all.’ Merely to be there was a cure for weariness, fear and sadness.

J.R.R. Tolkien

Until our move three years ago, our three children (then aged 8 to 14) shared the same, small 10’ by 13’ bedroom. For 15 years, we had lived in a 1400 sq. foot townhome together with my mother-in-law, and she had the master bedroom. It certainly forced us to use our space deliberately, creatively, and with buckets of compromise.2 In a world where every individual is assumed to have the right to a private room, puzzling three children into a tiny space with bunk and loft beds, bookshelves, and clothes cubbies was not only an anomaly, but struck some friends and family as simply undoable. While there were plenty of challenging moments, especially during arguments (“Well, I am going to my room!” followed by “Oh yeah? Me too!”), the constraints of the environment produced a strong and lasting bond between the siblings. The smallness of the space forced them to learn tolerance, compromise, and self-denial, accompanied by a depth of camaraderie that fewer and fewer siblings experience. Their environment forged their interactions and the depth of their connection.

Within the home, environment matters not only in child rearing, it is also fundamental in shaping our interactions with tech. Most often attempts at curtailing digital device use focus on the self: How to refrain from checking behavior, how to focus our attention better, or how to reshape our minds to be present in the moment. Yet in order to produce lasting effects we need to turn things inside out, away from the self, and toward reshaping our surrounding environment. And currently nothing dominates our personal space as ubiquitously as screens.

Polling of 2,000 adults in the U.S. found more than 6,259 hours a year are spent tethered to gadgets such as phones, laptops and televisions. This translates into 44 years of life spent staring at a screen. The average U.S. household boasted an average of 11 connected devices in 2019, some statistics suggesting that this number went up to 22 devices per household post-pandemic. It seems patently unrealistic to expect that willpower alone will save us from compulsively turning our attention to screens. Algorithms are designed to keep us hooked. We can try our best, we sometimes succeed for a while, but we are ultimately powerless to change our digital habits unless we change our surroundings.

A fascinating recent article pointed out by

— What If All Our Residence Halls Were Tech Free? — discusses the idea of taking decisive action in shaping our environment by reducing the presence of personal tech in Christian College settings. The author suggests that Amish are not “radical” because they chose to shun particular technologies, but rather “because they actually make decisions, rather than allowing the decision to be made for them by something called ‘progress.’”So what type of decisions can help us to shape our environment to allow us to grow in our relationships, strengthen our family bonds, and direct our attention not toward screens, but each other?

Starting with scaffolds

Embarking on change is daunting, and it feels much easier to throw up one’s hands and declare surrender. The alternative takes work, self-denial, and perseverance. This is not a popular path to take, but one that leads to the type of freedom produced by unwavering commitment. I can affirm that it is most definitely worth the effort — for you, and all those around you.

When beginning to address changes in the environment, the following scaffolds are helpful starting steps in making a home for humans. Yet, these practices do not lead to permanent change if you do not simultaneously build your living space around a solid foundation of placing people first. In their book The Distracted Mind, Adam Gazzaley and Larry D. Rosen remind us that digital detox strategies provide only a temporary solution:

“… there is no evidence that extended tech detoxes actually work. Sure, you might feel better for an evening, a day, or even a weekend, but when that detox time is over your are right back to your information-foraging behavior, frantically dividing your attention to catch up with all that you missed out on while technically disconnected. Just like short term diets and drug or alcohol detox programs, unless you change your environment and routines, it won’t be long before you return to the same old habits.”

Thus, take the following suggestions not as the end-point, but as first steps along a journey to reshaping the focus of your home.

At the beginning of May, I organized a Digital Detox Community, where a large group of readers committed to a 30-day detox. I recommend that you read the ‘game plan’ section as it contains detailed practical guidance. If you would like to download and print the digital detox game plan you can do so here. The pdf document at the end of the post includes a (very) simple note page where you can plan your specific usage rules for the month.

To assess your level of nomophobia - anxiety caused by not having your mobile with you at all times - you can take a test here or here. It is helpful to gain insight in your level of dependency.

Make an honest inventory of your overall tech use. Most people grossly underestimate how much time they actually spend online. This is a helpful article in Popular Mechanics on assessing your device habits, or you can try Checky or

’s Unmachining Self-AssessmentIf you want to limit your daily use of your smartphone or specific websites, there are apps that will block your access for specified amounts of time each day. Please note that I have never tried these apps myself (as I don’t have a mobile phone), so check reviews to see if any of these might be a good fit for you:

For specific methods to reduce your device use, check out the Air Method on Stay Grounded by

When working on your computer, close down all other programs or apps (do not just minimize them)

Set yourself specific checking times per day, i.e. three times per day. This reduces stress, and produces better overall well-being.

Turn all alerts off. Keep your phone out of reach and even better, move your it to another room. When driving put your phone in the trunk of your car.

One of the most helpful practical steps you can take, is moving from a smart phone to an old-fashioned flip phone or a “dumb phone”. This drastically reduces your effort exerted on behavior management. Check out this post on the Best Dumbphones of 2023 by

. Or you can take an even more radical approach by not using a mobile phone at all. I can attest that this is perfectly feasible, albeit inconvenient at times.

The Distracted Mind contains further strategies that help you to redirect your mind to reality such as:

nature exposure

face-to-face conversations (shown to reduce stress)

exercise (boosts brain function and improves attention)

short 10 min. naps (improves cognitive function)

laughing

reading (we experience major brain shifts when reading immersive fiction). See my post Rehabilitating Ferals of the Digital Age for readings lists and inspiration.

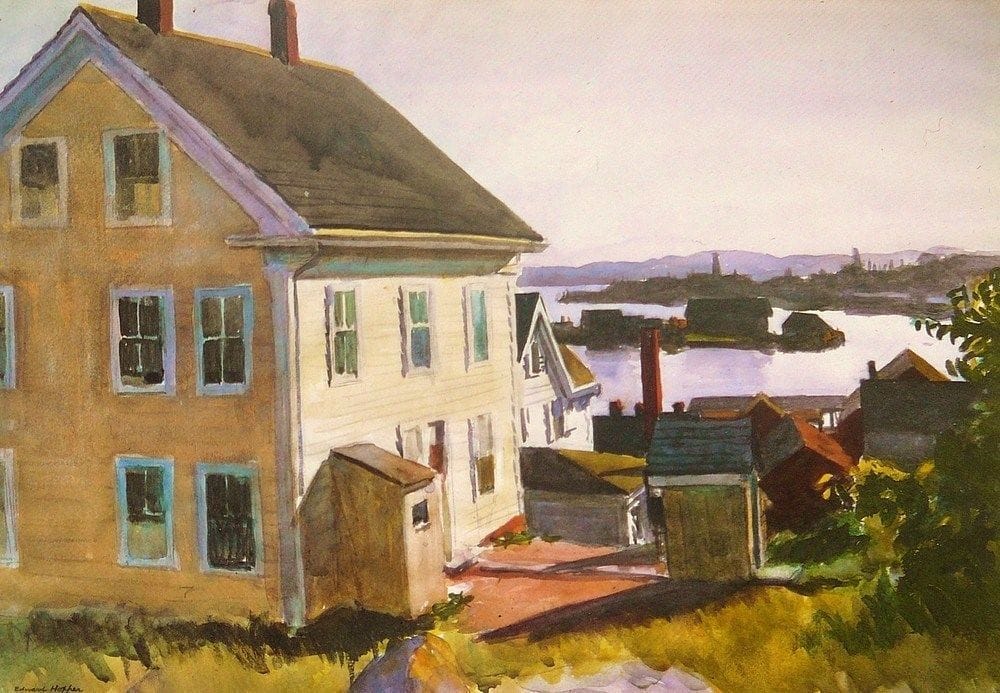

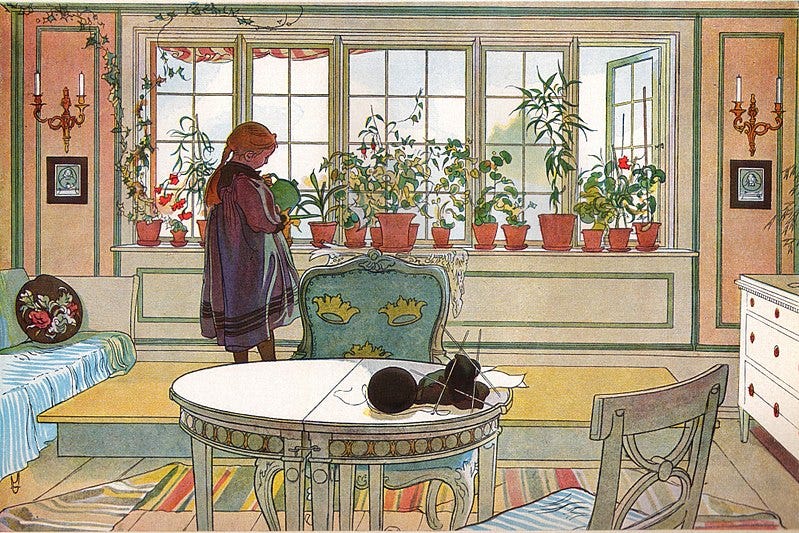

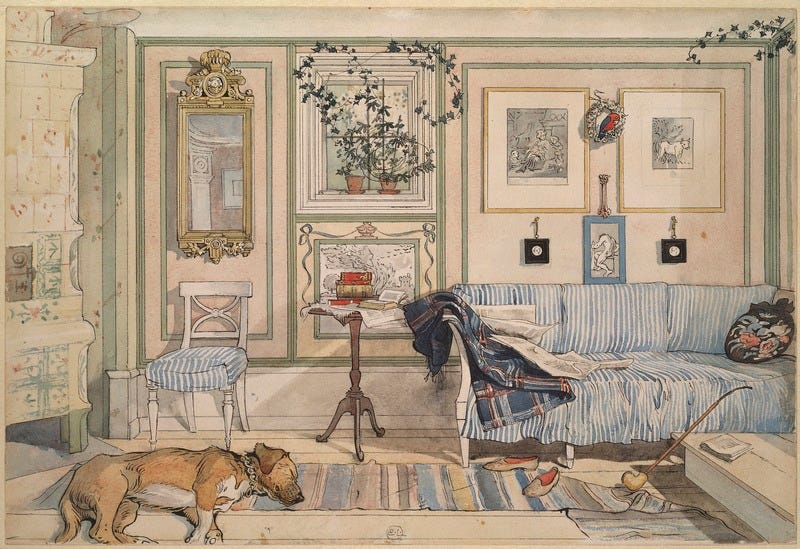

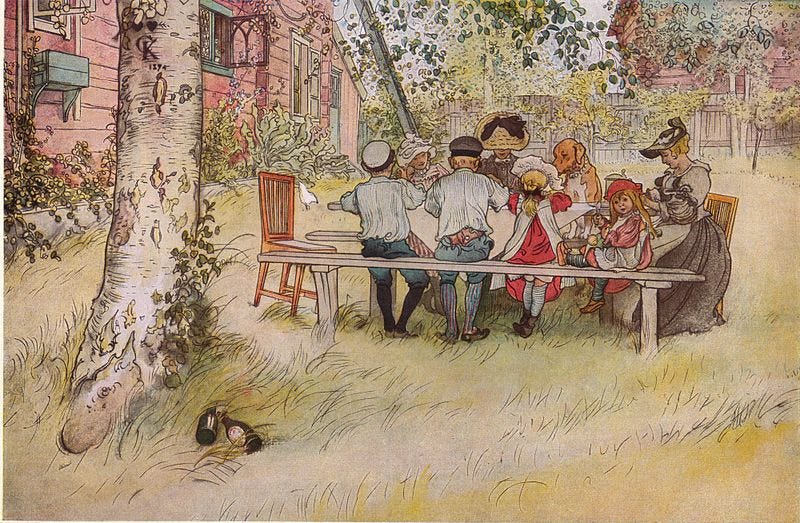

Every Home Has an Altar

Whenever I visit a new home, I note where my attention is naturally drawn. Often, the place my attention comes to rest turns out to be the home’s altar, its symbolic or literal focus point. At the core of our family’s living space is our large kitchen table, facing a window and a wall brimming with books, small classic paintings, an icon, a stack of Bibles, plants, and currently sports our youngest boy’s latest clay sculptures of chicken heads and grotesquely funny faces. This means my attention either rests on the people sitting at the table around me, the outdoors, on books, or on artful works. Not exactly a Martha Stewart moment, but our altar reflects our family at the core, surrounded with books, art, nature, faith, and creative projects.

We do not have any visible screens in our main living space. We do use technology, but it does not dominate our environment. Within the main area, tech is stored in a wooden cabinet by the stairwell, away from the center of attention. Having it enclosed has the added benefit of reducing temptation to quickly check something online. However, having a particularly addictive personality myself, I find that I have to actually store my laptop in my husband’s office upstairs after my morning computer time to resist the urge.

When our children were younger, they had no screen time at all. As they got a bit older, starting at around age 5, we would have a common movie evening on the weekends. Us as parents kept to the same diet. We still keep the weekend film rule, which allows for a rhythm to the week, rather than expecting passive entertainment on a daily basis. We have various rules about computer time and type of use (ranging from none for our 12-year old to self-directed use for our 18-year old).

We only have two mobile phones in the home (my husband’s and our university-aged daughter’s). My husband’s stays in his office and is used for business, travel, or photos. Our daughter uses her phone mainly for arranging plans, music, and podcasts, and it is never used at the family table. One of the most important changes you can make to your environment, is to keep your phones away from your body and out of reach.

commented that, “It would be so easy to designate e.g. a drawer in an end-table and make an individual or family policy: the phone stays there, and you go there to use the phone (and use it nowhere else in the house). You might put a chair by it and imagine that you’ll go, say, every X interval.” There is never a better moment than now to start with this small, but powerful, environmental change.If your phone is visible, even if you are not actively engaged with it, it negatively affects relationships with others. It keeps the mind divided and signals that the conversation could get interrupted at any moment. In a study conducted by researchers at the University of Essex, “the mere presence of phones inhibited the interpersonal closeness and trust, and reduced the extent to which individuals felt empathy and understanding from their partners.”

Arranging our main living environment without the draw of screens directs our attention towards each other, our present environment, or ideas and projects we are pursuing. When screens are visibly present, they suggest an instant solution, continually reminding us of how easy it would be to fall into waves of entertainment.

Gazzaley and Rosen point out how accessibility is at the crux of our constantly shifting attention:

The more readily available a new patch of information is (or even seems to be), the earlier the time someone will disengage from his or her current source. It is essentially the same for animals foraging for food; if another tree full of nuts is sitting right there, a squirrel is going to take the leap earlier to this new patch than if it had to travel far to get to another nut-filled tree.

Perpetual digital pacifiers create a vicious cycle eventually leading to disengagement and boredom when faced with real-time environment. In her 2011 book Alone Together, Sherry Turkle suggests that we now live as “postfamilial families”, where we each spend time tethered to our own devices in our own rooms, spending more time with technology than with each other. She relates her conversation with Hank, a law professor in his late thirties, who spends more than twelve hours a day on the Net:

Stepping out of a computer game is disorienting, but so is stepping out of his e-mail. “Leaving the bubble”, Hank says, “makes the flat time with my family harder. Like it’s taking place in slow motion. I’m short with them.” After dinner with his family, Hank is grateful to return to the cool shade of his online life.

Living as “postfamilial” families, where screens have replaced human face-to-face connections, has a long-lasting profound impact on how we value human relationships. Gazzaley and Rosen report that an analysis of data, “from over fourteen thousand college students over the past thirty years shows that since the year 2000, young people have reported a dramatic decline in interest in other people.” Further, a University of Michigan study found that todays generation scored about 40 percent lower in empathy than their counterparts did twenty or thirty years ago.

If we are to make a home where relationships are valued, we need to make a decisive choice to put people first and screens out of view.

Screen-Free Living Spaces

Accessibility to screens is of special concern when it comes to bedrooms. I could regale you with horror stories about disturbing online encounters, eating disorder influencers, or accessing porn via Spotify. If you want to be horrified and warned read: So your tween wants a smartphone? Read this first (thanks to

for linking this article).Keeping screens out of bedrooms is essential. The temptations are too immense and too accessible. No matter how many parent controls you install, many kids find hacks to work around them. Do not fall for the hope that your child would never access pornography or inappropriate content, because even if they were not to seek it out deliberately, they are highly likely to encounter it accidentally.

As a stark reminder, consider these facts:

90 % of teens have viewed porn online, and 10 % admit to daily use.

1 in 4 Children have had online sexual encounters with adults via social media. Nearly 1 in 3 teen girls have been approached by adults asking for nudes, while 1 in 6 girls aged 9 -12 years have interacted sexually with an adult on these platforms.

83% of children do not tell trusted adults about abuse they encounter online

Keeping all devices in a public common space removes the large weight of temptation and unbearable burden of self-control. If you create an environment where screens can be viewed by everyone, it affirms their proper use and circumvents the development of online secrets.

One of the most sacred places in a home is the family meal table. It is literally designed for us to commune, arranged so that we look across at each other’s faces while we share the food placed in the center. It is also a perfect place to start retraining tolerance for being away from devices. Mealtimes are short enough and important enough to place screens far out of reach. Even the younger generation is recognizing the importance of uninterrupted meals as is evident in “cellphone stack”, a game where everyone at the table places their phones at the center of the table, one on top of the other, and whoever looks at their device before the check arrives must pay the entire bill.

Gazzaley and Rosen report that, “A recent metanalysis found that frequent family meals are associated with more positive outcomes including better children and adolescent psychosocial health as well as improved family relationships.”

Whether you are Christian or not, family meal time is where “church” happens in the home. We are nourished, we talk about our experiences, concerns, and ideas, and through this we unite and build our bonds. I am under no illusion that meals always pass peaceably; they can involve tantrums from little ones, brooding looks from older ones, and a generous serving of bickering (at least I hope that this does not just describe us), but there is no better glue to bind us as a family. And in order to demonstrate that we are fully committed to the moment and the people sitting at the table around us, meal time should remain free of all devices.

Many of you who read this are parents or maybe are planning to be someday. Your choices and changes in your home environment will make a lasting impact on your parent-child relationship, your child’s current and future well-being, as well as carry down to the next generation. If children feel insecure about a parent’s love and attention, how could they possibly offer security and love to the coming generation? The way you choose to create your home environment has has a powerful exponential impact.

What is the altar of your home? Does it reflect what you want to be at the center of your focus? What change could you make in your home today to shift attention away from screens and towards each other and your environment?

We need homes made for humans. The wonderful part is that it is completely within your power to create such a home.

Until next time,

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), please consider supporting my work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a like, restack, or share.

Further Reading

If you would like further advice on navigating tech-use at home, take a look at the follow-up article, Charting the Course for Family Tech Use - Steering the ship, turbulent teenage seas, and the Postman Pledge:

Charting the Course for Family Tech Use

At the end of this article, former social media influencer Erin Loechner provides practical tools for scaling back tech in the home:

Turning the Algorithm Upside Down: The Opt-Out Family

Unconformed Education Live Zoom Event:

As a follow up to

’s and my recent post The Falvors of Faux History, and I would like to invite you to join us this Saturday,September 28th at 2pm EST for a live zoom meeting on “Teaching History” followed by a lively session of “Ask Us Anything”. The meeting is free to all subscribers. See post for details:

Teaching History & Ask Us Anything

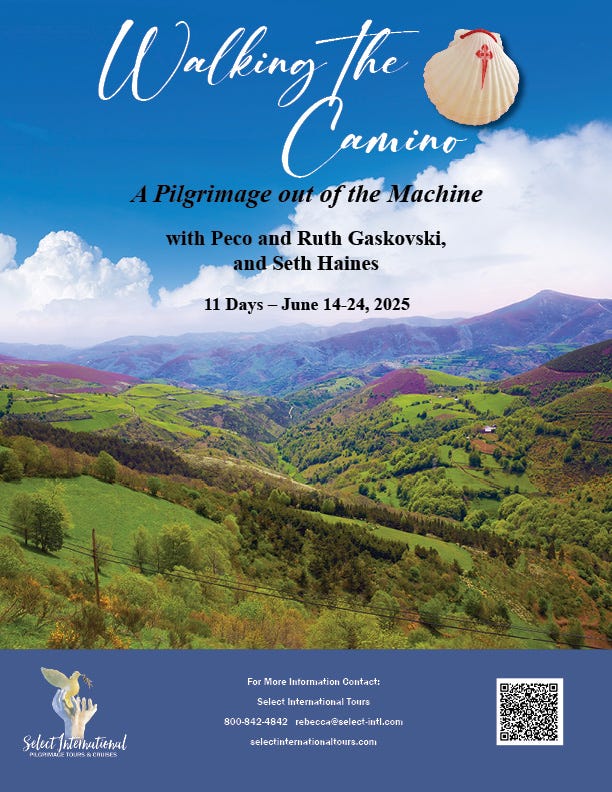

Come and join us on A Pilgrimage out of the Machine!

My husband Peco and I will be leading an eleven-day pilgrimage on the Camino trail in Spain next year, from June 14-24, 2025. Joining us, as co-leader, will be writer/photographer Seth Haines from The Examine. Space is limited so reserve your spot now :) You can read all about it here or view the brochure here. This trip is open to everyone, irrespective of religion or background.

At the time this post went out to around 2000 subscribers and School of the Unconformed has now just reached 13’000 readers.

Our decision to put family first, to homeschool, and to thus live on a single income, provided the needed commitment to live with less space.

I have the same questions about the "delay screens" approach. It is a good place to start -- deciding that our kids should not have these types of screens right now -- but as someone who does not use a smartphone, I am not comfortable with the idea that using a smartphone eventually will be a given for my children. As adults, they will of course choose for themselves. But while I have often thought that giving a kid a phone at, say, 16, and then supervising how they learn to use it, has some wisdom, I have also wondered to myself whether it would be better to try to convince them to adopt a dumbphone instead as the "adult" type of phone access rather than presuming that they will eventually get a smartphone and so it ought to be while they are still under my roof/close influence.

The difference of opinion here is about whether to "accept' a certain kind of lifestyle as inevitable or try to give our kids wisdom about what a good life might look like. Kdis will make their own decisions as adults but why presume that this decision will be "I will use a smartphone" or "I will use a smartphone without restriction?"

My own kids have been commenting recently about ways they might restrict their computer and cell phone use as adults. This is unprompted by me -- I guess it's just something that my older kids are beginning to think about as they grow and as they observe the decisions my husband and I make (for ourselves and on behalf of the whole family). My 13-year-old does not *want* a phone...I don't want to teach her to want one.

Also: when we built an addition onto our home a few years ago, we thought a lot about this family focal point ("altar"). We built the addition in order to house a fireplace and a piano, along with seating and a big dining table. Especially in the colder months, this is the natural gathering space for our family and for guests, and the focal points are A) the hearth, B) the artwork and crucifix above the hearth, and C) the piano, all of which are arranged together. I think (hope!) that this directs us toward good ways of spending time together.

Even though I understand the convenience of it, I hate to see a TV mounted above a fireplace. It means that you can't enjoy the hearthside without also seeing the TV right there, even if it is off.

That Tolkien quote is our house motto. We commissioned a simple work of art with those words and hangs above our mantle.

I really like the idea of making a choice instead of progress making the choice for us. We should be disgusted at the agency we've lost.