How to Grow a Garden in the Technopoly

Tessa Carman on the Postman Pledge, the Machine, and playing the long game

For those of you who prefer to read off paper rather than the screen, I have converted the post into an easily printable pdf file. Remember to come back and share your thoughts and comments! You can access the file here:

How to Grow a Garden in the Technopoly

Also, we are creating an accompanying visual guide to Simple Acts of Sanity: A Seed Catalogue and thus need your help: Please send us your photos of “random acts of anachronism”! You can either send inline photos (not attachments) to schooloftheunconformed@proton.me or paste them into a reply to this Note. (For privacy purposes, please do not send photos that include facial shots.)

Navigating the Machine age calls for a clear understanding of the challenges we face, as well as practical solutions. Here at

, and at , we try to offer a bit of both. Yet it is in actual lives lived that we often best see how individuals and families are meeting these challenges in their own original ways, and where we might find inspiration for ourselves and perhaps patterns we might emulate.In our walk of faith we might turn to the lives of saints1 for guidance, or we might find encouragement in the biographies2 of extraordinary people. Today we would like to share an in-depth interview Peco and I had, not with a saint, nor someone with a bestselling biography, but with an ordinary person with extraordinary insights on how to resist the Machine with joy and intellectual acumen.

You may have come across

(mother, writer, poet, and teacher from Minnesota farm country) if you read her incredibly in-depth interview with in Mere Orthodoxy (it’s an est. 62 min read!) or any of her various articles that appeared in the Front Porch Republic, Ekstasis, Fare Forward, Mere Orthodoxy, Plough, and The Lamp, among other publications. If you were at the Front Porch Republic conference last fall, you would have heard her speak on “The Joy of Tech Resistance”, or maybe you “met” her online during our Unmachined Coffee House discussion. If you were particularly fortunate, as we have been, your children might have had the pleasure of being students in one of the literature or mythology classes she teaches online.If you have not heard of Tessa yet, our recent interview is a great introduction to one of the most insightful voices in the Machine conversation, and includes her practical guidance for cultivating family, community, and playing the long game.

Was there a moment in your life when you suddenly realized that digital technology had become a problem in our society?

Not really. I had no epiphany about digital technology in particular, but when I was becoming more aware of the world, it was always clear that there’d been a general trend of disintegrating norms and institutions and especially of communal life. I think it was also always clear that certain kinds of practices steal our attention from what matters, and there are other practices that deepen our attention, and cultivate it toward worthy things. Digital devices are just the next, immensely powerful thing that erodes traditions and cultures, and that contributes to what Jacques Ellul called the “technological society,” and which Neil Postman called technopoly—“the submission of all forms of cultural life to the sovereignty of technique and technology.”

As a child, for instance, I was perfectly aware that television could powerfully distract attention from better things, which is partly why my parents had the informal rule that we couldn’t watch anything if we had friends over (unless we had some special movie event planned).

I was really blessed by a lot of things growing up. One of those things was a strong family culture—and here I mean extended family, not merely nuclear. We really knew how to work hard together and to play hard together. One family trait that got passed on to me was a suspicion of whatever the crowd, or herd, was doing. If something was popular, that was a reason to be cautious. Another family tendency was an aversion toward being controlled, whether it was through alcohol or too much television or getting sucked in by propaganda or whatever. There was also a lot of emphasis on personal integrity.

So, I think that background and attitude definitely helped shape my approach to certain things. I was also blessed by having a lot of experience with real things, including lots of books and time outdoors (including doing chores that I did not want to do at the time!), as well as just solid people of different ages and stages of life, great relationships with aunts and uncles, a caring mom, a strong dad who pushed us to think clearly, to be creative and to think outside of the box, and to never get caught up in self-pity. I was also exposed to lots of different kinds of tools: cream separators, tractors, log skidders, slide projectors, typewriters, eight-track players, phonographs, etc.

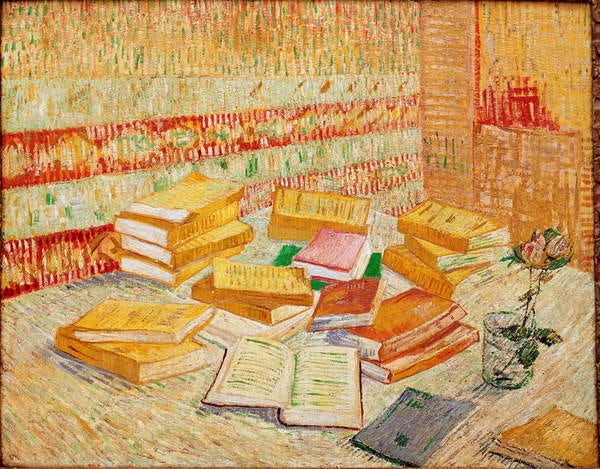

So when I read Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains in college (which a certain young man whom I wanted to know better had also read), that was significant: It named trends that I could see around me, but I also found continuity with other reading I’d done before then. For instance, I read a lot of literary/theological blogs and magazines in high school, and then I’d find book recommendations and one thing would lead to another. At age 15, for instance, I read Eric Brende’s memoir Better Off: Flipping the Switch on Technology, where he tells of living with an Amish community during his first year of marriage as part of his research at MIT. The question he wanted to answer was, how much—and what kinds of—“technology” do we actually need to live well? I also read my first Wendell Berry book that same year—The Way of Ignorance, when it was new on the library shelves—and had started researching education (I’d done public, private, and home school up to that point), so I was reading Charlotte Mason, Susan Wise Bauer, and John Taylor Gatto, and also reading a bunch of C.S. Lewis and G.K. Chesterton, and always fairy tales.

So I guess the question of technology has always been there for me, in a way, besides all the other questions I was trying to answer about theology and poetry and literature and education—basically all those things that have to do with living well.

On a practical level, what does technology use in your family look like?

During our first year of marriage, my husband and I didn’t have internet at our apartment, and we had no car, so we biked to work and everywhere else. (It took some creativity—we were not living in a walkable place at all! But it was worth it.) One time while in the teachers’ lounge at the school where we both worked, I remember the school nurse (probably after hearing about our playing records and our not having smartphones), called us “Amish”! It was hilarious. We’re not half so interesting, I hope I said, but probably didn’t. The amusing thing was that we weren’t all that unique. We hadn’t really sacrificed anything (I’d love to go back to biking everywhere and not having internet at home if we could!) and I could think of plenty of folks more fascinating, and more nonconformist, than we were.

So we lived a simpler life then! Nowadays, we have more going on at home: three children, two cats, a backyard with a garden we try to cultivate. Things have changed a lot through our lives: at one point we were both working mostly from home with two kids in a two-bedroom box apartment with a slab of concrete as our front yard (but in a lovely walkable town). But the principles with which we’ve tried to live have remained the same:

We want our home to be a place of making and of creativity, a place of hospitality, and a place where the good, true, and beautiful can be pursued in relationship. We want there to be a proper ordering of life so that there’s room for silence, for singing, for solitude, and for community and communion.

So technology—and everything that we are stewards of—needs to bend to those principles. I love how Andy Crouch puts it in his very helpful book The Tech-Wise Family: Everything should be in its proper place, and that goes for our tools and time as well as toys and books and kitchen utensils. What Crouch also notes is that stating your family goals explicitly—such as growth in wisdom and courage—helps you to discern whether a certain tool is needed for a task. (As one of my dad’s sayings goes, “Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should.” And the corollary, of course, is just because other people are doing it doesn’t mean you should.) Will this help me, or my child, grow in wisdom and courage? Does this practice help cultivate attention, and appreciation of beauty and truth and goodness?

That said, as far as tools go, we want our children to learn to use many different kinds of tools and instruments well: pencils, calligraphy pens, brush paints, whittling knives, sanders, pianos, guitars, crochet needles, typewriters, bread scrapers, garden hoes (don’t underestimate the value of a well-made hoe!), compasses, etc. Behind all of this, of course, is the goal of forming the whole person well, including their minds, voices, and bodies.

(I just read this line the other day in Alexander Langlands’ Cræft: An Inquiry Into the Origins and True Meaning of Traditional Crafts: “As John Ruskin put it in 1859, in our hands, we have ‘the subtlest of all machines’.”)

As far as digital technology goes—it depends on the season. When we both started teaching online (and had our first child), we needed a car and needed internet access. We’ve never needed smartphones (when we got married my husband traded in his smartphone for a dumb phone), not even when traveling abroad, so we don’t have them. (I sometimes want to toss my cell phone and go back to a land line!) We got an outdated, non-wifi-connected GPS to keep in our car when we moved to a bigger city. I prefer to wash dishes by hand for various reasons, so I don’t use the washing machine much.

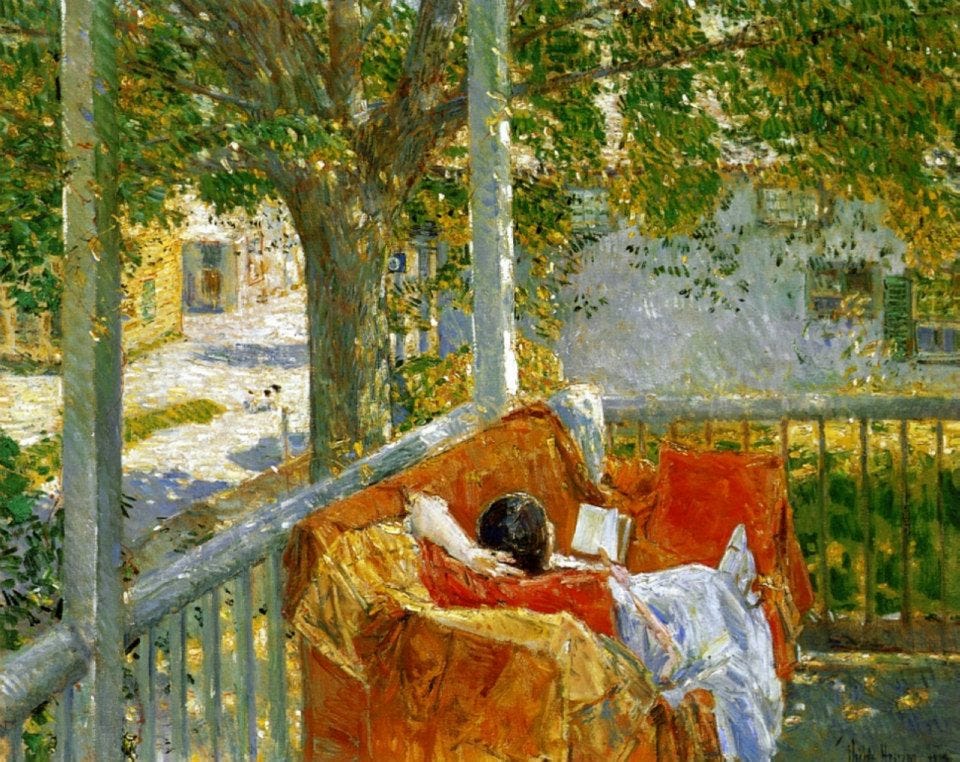

We read a lot, we listen to CDs and vinyl records; we stream music and audiobooks sometimes, but we want as much as possible to make use of the limits provided by physical objects rather than being overwhelmed by the seemingly infinite access the internet offers. Sometimes we’ll watch a movie as a family (and some classic episodes of shows like Bonanza), but we’ve never had a television. We do have a movie projector and we love doing movie nights with friends. We make food and have people over. We dance. We read aloud. We sing. We recite poems and make up silly rhymes together. We write letters. We take adequate photos on kiddie cameras and really lovely ones on my husband’s analog camera; we’re building a family collection of physical photo albums, in addition to all the digital stuff.

We allow space for the kids to play outside a lot, play with lots of Legos, sit with books of all sorts. (The quiet in between activities is probably the best times—when they’re processing things on their own and then come up with some new project or some stumper of a question for us!) We go to museums; we work in the backyard. My husband has a budding woodworking shop in the garage that the kids help with. We hike. We host play readings and music nights. We visit my family’s farm in Minnesota whenever we can, since being at my grandpa’s farm was so formative for me and my brothers. We pray and go to church together.

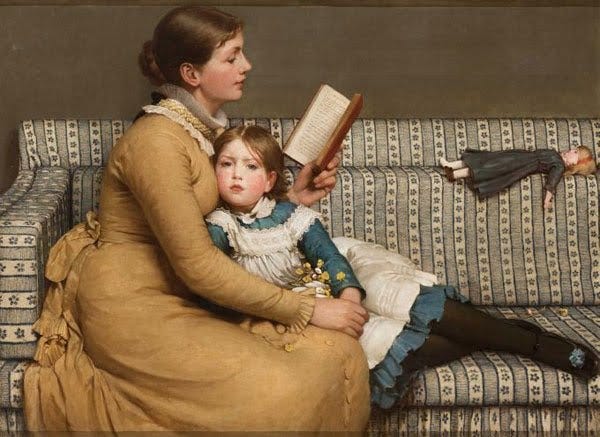

We involve our children in pretty nearly everything; they’re there for our reading of Twelfth Night, they’re listening to the poetry recitations and conversations, they’re organizing the living room in preparation for guests, they’re staying up too late because of a conversation Mom and Dad got into with friends.

We homeschool (as the official term goes - it’s not my preferred term, since all of life is education) and take part in co-ops right now, but if we send our children to school, among other things it will need to be one that has no digital technology in the classroom (and there are schools doing this!). (I already know of one school at which parents of teenagers have made a pact on their own initiative to not give their kids smartphones.)

In our work, we try to set limits for ourselves and to make it possible for others to do so as well; in my online teaching, I try to make clear that students should not be available online all the time, and neither should I.

(A nonprofit idea I’ve had is a consultancy that helps businesses be more human-friendly! I.e.— don’t require smartphones for all but the most intense jobs, don’t require 24/7 availability, don’t rely on smartphone apps, don’t rely on digital calendars so much, allow for time for your employee to be human—i.e., to take care of sick relatives, to go to church— and don’t put all your digital eggs in one basket such that your employees can’t do anything if “the computer says I can’t.”)

One reason I’m not tempted by a smartphone is that I already have enough trouble limiting laptop use! That’s enough for me to worry about. My husband uses some programs that shut out Youtube and the internet itself when he’s writing or researching; the internet is a massive library and so is super helpful for scholars, but it’s still a digital screen and black hole.

Above all, we’re always trying to be wiser people and to learn from people who are wiser and more experienced than we are (dead and alive). And we’re always asking whether something is helping or hindering us in our goals, or in the habits we’re trying to form in ourselves and in our children.

In your writing and presentations, you share that you are part of a committed group of parents who has pledged to keep kids off social media and smartphones as well as limit parental use of technology. Can you share what your experience has been like with this group?

For more on the Postman Pledge group, readers can check out this profile and this interview at Front Porch Republic with the founder of the group.

So far our experience has been encouraging! My husband and I have moved a few times after college, and each time we had to rebuild community, but we always had something—even a kernel—to start with. We’d been blessed with very good friends from college who were similarly against-the-grain, as you might say—one couple also didn’t have smartphones or internet, another couple would host music nights and Anglo-Saxon (Old English language) club, and we would all make large brunches together. But of course you don’t always find those people right away.

When we moved to where we are currently, we were encouraged to find this group especially because these were people with older kids who were committing themselves to giving their family a better life than the one on offer by the zeitgeist, but they also had the courage and foresight to see that, especially during the developmental ages of middle school and high school, young people need to be with other people, to have friends, who are doing similar things. When children are under 10, that’s one stage—home life is especially formative. But it’s another game, or another level, when your kids get to the double digits. So you still need to lay a foundation before that time, but you also need to be aware that the middle-school and high-school stage is a place where children start looking outwards more, asking how and why, and they need good friends and mentors and examples outside the home. We’re not at the double-digit stage ourselves, but through our teaching and simply being in community we’re always encouraged to meet children older than ours who are curious and alive and thriving — and from whom I have much to learn!

One nice thing about knowing that some other family has made the Postman Pledge is that there’s another level of trust with each other — for instance, while playing at a friend’s house, a kid is far less likely to stumble onto porn on someone’s smartphone, and children aren’t seeing the adults in their lives on phones so often. Instead we’re getting together to sing Christmas carols by lantern light and learning folk dances together.

I try to tell everyone I know about this group, since I believe parents absolutely need to work together: Parents often feel helpless and alone, but some of the most powerful work throughout history has been done by brave housewives and fathers who banded together for the sake of the good of their children and their communities.

Is this an approach that families can take, who are already in the depths of technology overuse or even addiction? If so, what considerations would you keep in mind when making a Postman Pledge decision?

If families are dealing with addiction and overuse, joining a group of families who are committed to living better together and encouraging each other toward that end would seem very helpful indeed! This is exactly why some Postman Pledge parents who knew they were dealing with unhealthy habits themselves have appreciated the pledge (see this piece here).

Jeanne and David Schindler started the group, so they are the people to talk with as far as getting advice on forming a group.

For those in the depths of addiction, it’s above my pay grade to address those particular situations. The only thing to say is that you need to want to get out. And you need to be willing to change things — sometimes huge things — in order to have a better life.

Assuming you find people to make the pledge with, or even before you find those people (since sometimes you need to make your own pledge first), the first thing to be clear in your own mind about is why you want to do this. What is the goal? Is it to have accountability in pursuing a more free, beautiful, courageous life? (It shouldn’t be achieving a perfectly controlled life — that’s just another version of what the Machine promises). Is it to use the short time we have on this earth to pursue what’s true and good and to waste as little time as possible on hindrances to that pursuit? Name the goal, and then never forget it.

Some people have raised the following concern with regard to homeschooling children or committing to a Postman Pledge group: How will they hold jobs that are meaningful, how will they navigate in a world where they are expected to follow and not lead, where they are being indoctrinated, not educated? It's well and good to say that we can homeschool and associate with like-minded folks, but what about when they need to move out and start living their own lives? Some might answer this with the need for building a “parallel polis”; what do you think of that? Are there any other paths to living differently as adults in a deeply machined society?

Let me give a little bit more of my own background to begin answering this common concern.

Growing up, I observed family and friends being raised differently from us, and my dad would point out the folks who were raised in fear—“sheltered” was often the term—and then went off the deep end when they left home. The thing was, they were sheltered not merely from “the world”—say, pop music and movies—but also from great art and from learning how to think clearly, and often from healthy communities as well. (And often they did not know much history; my dad would often say that one ought to learn history so that no one can fool you.)

My dad did not raise us in fear. He never wanted us to live in fear of anything, or to be intimidated by anything. The only thing to fear was of doing or taking part in evil. From that we needed to run. But we ought not live in fear.

One of the things my dad couldn’t stand was cultish and abusive authority. He knew exactly how important proper authority was: He is a faithful Christian, and he led our family well, and is a great teacher himself. He never commiserated with me when I had a complaint about a teacher. My job was to be a good student, and the teacher’s job was to teach me. I was under authority. But control and manipulation, and especially the cult of personality—those things he was repulsed by. Those things overstepped the proper bounds of authority. If I ever tell you something that’s not true, he’d tell his students and kids, don’t follow me.

I think that was all really healthy for my brothers and me. We saw examples of people living legalistic lives, caring more about appearances or pleasure than the truth, and giving up on learning to think, or simply giving up altogether. (Another one of my dad’s favorite lines (from an obscure but well-loved movie): “There will always be hard things…The only sad thing is giving up.”)

And that, I believe, is underneath a lot of our fears about community, tradition, etc. On one hand, we don’t know the difference between solitude (good) and isolation (bad). We don’t know what a healthy community looks like because too often we’ve not seen it—and that’s a super difficult place to be. But also, perhaps above all, too few of us have seen a healthy example of authority held well. And authority has to do with tradition as well as particular offices and duties that people hold.

I’ve been incredibly blessed to have a strong father who governed our household well, who respected us and therefore pushed us to be the best we could be, and then let us “live our dreams,” settling back to be our counselor-when-called-on.

We’re afraid of being controlled by the Machine. But we’re also afraid of being controlled and manipulated by other people. This is completely fair; the twentieth century saw the rise of totalitarianism, after all.

Here’s one other piece to consider: The homeschoolers and classical school kids I’ve taught, met, and observed throughout my life have overwhelmingly been some of the most capable, curious, intelligent, polite, mature, and skilled people I know. I’ve taught homeschooled middle schoolers who are far more capable and thoughtful and articulate than most of my husband’s undergraduate students. The only reason I would worry about them is that they will get to college and find it difficult to find a kindred spirit, or to find someone who isn’t on their phone all the time.

So, let’s look at homeschooling. I actually don’t really like the term since it has limited usefulness, and it gives rise to strange scenes in some people’s minds, like an overbearing mother shutting her kids inside all day. Sure that might happen, but that’s not the definition of homeschooling.

The question is, how do we raise our children well? How do you raise a human being? That’s what we need to ask when we talk about education. And this goes back to what it means to be a human being and what a human being is meant for, which then leads to your duties as a human and as a parent. (The collected works of Charlotte Mason have been hugely helpful for me in studying the very big question of how one raises a human being, in all its intricate complexity.) What do you owe your children? What reality (and Reality) are you preparing them for? What do you (and your community) need to do in order to do that well? Only you can answer that question (your children are entrusted to you, after all), but you should be observing and gleaning and learning from everything you can. Don’t fool yourself, and keep your eyes open.

What makes a meaningful life? How do we prepare our children for a meaningful life?

Our goal should be to give our children a strong foundation from which they can then grow and thrive. We should fill our homes with goodness and beauty, practice virtuous habits, serve others together, invite people into our homes, associate with different kinds of people, practice good habits of conversation, give your children developmentally appropriate responsibilities, and not let quarrels get in the way of good arguments.

One reason I enjoy home educating is that I can (1) better cultivate key relationships with and amongst my children in their earliest years, and (2) they can have a more holistic experience of their neighborhood and the world. I want them to be better prepared to take care of themselves, have a better chance at a meaningful life, than the limited scope the zeitgeist has on offer.

So, whether my kids are being “homeschooled” or attend a classical school or some mixture, my goal is to cultivate persons, not computers, who are part of a natural, ordinary community—which is an uphill battle, certainly, since our society is intentionally built to lock away people from each other, and to treat people like things. But it’s a joyful battle that I deem worth it, because of the immeasurable worth of my children’s souls.

I think it’s also worth remembering that people have been sounding the alarm on how we officially school children, and on how much our traditions have disintegrated such that it can be hard to find positive visions of the life we’re seeking. These words from New York public school teacher John Taylor Gatto3 are really worth pondering. Here he is accepting a teaching award in 1990:

Our school crisis is a reflection of this greater social crisis. We seem to have lost our identity. Children and old people are penned up and locked away from the business of the world to a degree without precedent - nobody talks to them anymore and without children and old people mixing in daily life a community has no future and no past, only a continuous present. In fact, the name "community" hardly applies to the way we interact with each other. We live in networks, not communities, and everyone I know is lonely because of that. In some strange way school is a major actor in this tragedy just as it is a major actor in the widening guilt among social classes. Using school as a sorting mechanism we appear to be on the way to creating a caste system, complete with untouchables who wander through subway trains begging and sleep on the streets.

I’d encourage you to read the whole speech. Note that Gatto is speaking in 1990. The problems he saw are still with us — they’re just worse. But I think it’s instructive to note how some problems we have — such as with attention — are not new, but the struggle for cultivating habits of attention and rebuilding tradition and culture seemingly out of whole cloth has certainly shifted with the rise of machine-thinking and machine technologies in the twentieth century.

What if young adults encounter propaganda and the like? All we can do is raise them with habits of good thinking, with strong relationships, and with a love and knowledge of real things—and to model those things ourselves—and then to let them make their decisions in life. A taste for and love of truth is the best preparation for detecting the fake.

Sure, make a parallel polis! Why not? There are many ways to live well in this world. Learn from Vaclav Benda, learn from the Amish, learn from the Bruderhof, learn from L’Arche communities, learn from the saints, learn from everyone you can. As the Bruderhof say, “Another life is possible.” It’s not going to look the same because that’s what we’re avoiding, isn’t it? The Machine wants to control and dictate your every move; the Machine does not want you to be human. It wants you to live on Camazotz4.

So you need to fight it: Recognize what you’ve been given, steward it well, and then figure out what your role is. (Also, in addition to the periodical Plough Quarterly, see Ashley Colby’s podcast

for all manner of examples of people living inspiring lives adjacent to the Machine.)You teach English literature to high school students and, having witnessed our own daughter’s experience in your class, inspire your students with your love of classics and poetry. With that in mind, I wanted to bring this reader comment to your attention:

I don't think there's any stopping technology. I think it's baked into the cake. I think, as Ted Chiang has written in his fiction, that it begins in us: "We don’t normally think of it as such, but writing is a technology, which means that a literate person is someone whose thought processes are technologically mediated. We became cognitive cyborgs as soon as we became fluent readers, and the consequences of that were profound." What are your thoughts on this?

In one sense, this is an important point: We often use “technology” to mean electric- or gas-powered machines, or computer technology. But humans have always made technology—that is, we've always made tools.

But we humans were always makers: there’s nothing inherently “mechanical” in the modern sense about that. (Interestingly, “mechanic” used to mean a manual laborer or artisan.) Poet means maker. “Cyborg,” however, is a computer metaphor, so it would be anachronistic to apply the term to all kinds of tools—and I would resist it particularly because the person-as-computer metaphor has been so disastrously destructive.

It’s certainly true that our tools shape how we see the world, however, and it’s worth studying how, for instance, the printing press and the microphone each played a role in changing people’s experience of the liturgy.

Considering all this, however, should help us put to bed the notion that “technology is neutral.” Neutral in what way? Fine, you can’t put a hammer on trial, but tools do shape us: they shape our lives, how we think, how we act. (My husband, who’s brilliant on all this stuff, reminded me of this line by Iris Murdoch: “Man is a creature who makes pictures of himself, and then comes to resemble the picture.”)

Words, too, shape us: Sloppy language kills clear thinking and makes it impossible. C.S. Lewis said, “when, however reverently, you have killed a word you have also, as far as in you lay, blotted from the human mind the thing that word originally stood for. Men do not long continue to think what they have forgotten how to say.”

The kinds of tools that came into the world during the (capital-M) Machine age are even more affecting. There’s a disintegrating, consuming quality to tools of the Machine. The Machine wishes to dominate. It’s a kind of black magic, really, overriding people’s wills and humanity. As my husband puts it, tools used to have to conform to human nature; now the goal is to change human (and every other kind of) nature through our tools. As Carl Schmitt said, “The machine has no tradition.”

Here’s something interesting: Tolkien said the power of the One Ring was the power of the Machine: When asked, what is the Ring? Tolkien answered that is the “Machine,”

By [which] I intend all use of external plans or devices (apparatus) instead of developments of the inherent inner powers or talents – or even the use of these talents with the corrupted motive of dominating: bulldozing the real world, or coercing other wills.

For more on this, see Michael Toscano’s wonderful essay on Tolkien in Fare Forward.

In your interview with , you mentioned that you were considering organizing a seminar for high schoolers and adults where you would read literature on the Machine. Would you mind sharing what books you would include on your reading list?

This is a great reminder to put this into action! Here are some readings I’d love to include, though I certainly would have to choose carefully from amongst them:

Tolkien, The Lord of the Rings and “On Fairy-Stories”

E.M. Forster, “The Machine Stops”

C.S. Lewis, Cosmic Trilogy (esp. That Hideous Strength)

Neil Postman, Technopoly

Jacques Ellul, The Technological Society and Propaganda

- , Feminism Against Progress

- , Alexandria

Aldo Leopold, A Sand County Almanac

Ivan Illich, Deschooling Society and Gender

- , Shop Class as Soulcraft, The World Beyond Your Head, Why We Drive

Poetry of R.S. Thomas, Robinson Jeffers

Wendell Berry, The Unsettling of America and The Hidden Wound

David Sax, The Revenge of Analog

Alexander Langlands, Cræft

Possibly Terry Gilliam’s Brazil

If you could give parents just one piece of advice with regard to technology use, what would it be?

Don’t neglect your post.

Your children are counting on you. Play the long game: You need to decide on what is best for your family and to live it out, no matter how popular or unpopular your decision is.

Live with conviction and joy. If you’re anxious and fearful, so will your kids be. If you’re joyful, full of interest in life, always looking to learn, and practiced at sticking to your convictions, chances are they will be too. Show them how to make hard decisions. Show them how to sacrifice. Show them how to love well.

Don’t be used. Be a free human being, and be willing to do what it takes for you and your family to live freely—that is, to be free to pursue the good and true and beautiful with joy.

If you could listen in on lots of teachers’ lounges, you’ll hear teachers saying, “I’m not worried about so-and-so; he’ll be all right. He’s got a good family.”

I’m a Christian, so I believe our lives are directed by Providence, that nothing is meaningless, the material world is composed of signs that point to its Creator, that Jesus Christ lived, died, and rose again from the dead, and that our purpose as human beings is to love God and be transformed into His likeness. That shapes my hope, and my approach to all these questions. This life is full of the long defeat, as Galadriel wisely observed, but there is always hope. We weren’t placed on this earth to live a cushy life. We were placed here to learn how to live well into eternity—for if our souls are eternal, it’s for eternity we must prepare. (The long game, indeed.) And in this life, that includes preparing how to die well.

You can find a comprehensive listing of all of Tessa Carman’s interviews and articles here. Here is a selection:

The Joy of Tech Resistance (video) - Presentation given at the 2023 Front Porch Republic Conference

On the Philosophy of Charlotte Mason with Ashley Colby (Doomer Optimism podcast)

“Following Christ in the Machine Age: A Conversation with Paul Kingsnorth,” Mere Orthodoxy, September 13, 2022

“At the Back of the North Wind: A World Worth Returning To,” Fare Forward, December 14, 2022

“Teens Need Tech Limits and Real-Life Relationships to Thrive,” Institute for Family Studies, December 14, 2022

“Joining the Dance: Setting Aside Screens to Build the City,” Front Porch Republic, November 15, 2022

“Becoming a Perennial: A Conversation with

,” Mere Orthodoxy, March 22, 2021“Lovers of Truth: C.S. Lewis and Elizabeth Anscombe,” Religion & Liberty Online, November 22, 2023

“Children Are Born Persons: Exploring Charlotte Mason’s First Principle of Education,” Institute for Classical Education, October 26, 2021

We would love to hear from you! Please share your thoughts, reflections, and questions in the comments below.

If you found this post helpful (or hopeful), and if you would like to support our work of putting together a book on “The Making of UnMachine Minds”, please consider supporting our work by becoming a paid subscriber, or simply show your appreciation with a like, restack, or share.

See How to Train Sheeple -A crash course in John Taylor Gatto’s educational machine resistance.

This is an allusion to the disembodied-brain-controlled planet in L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time, from "The Happy Medium" chapter (the scene I'm thinking of is the one in which every house on a particular street is exactly identical, "small square boxes painted grey," and each woman and child pair acts exactly the same—until there's an Aberration).

I have to admit I’m struggling here. I loved this interview, and my husband and I had these goals in mind for our family, and when we first got married we lived much like this family. And then we had kids, and we moved away from family and community in order to be able to afford to live out our values more fully, and let me be a stay at home mom and homeschool. And then we had a child with autism and mental disorders. And I tried to homeschool twice and it was a disaster. And we live in a rural, high poverty area where finding kindred spirits and community is extremely hard. I am an artist and my business is entirely based online (and it’s very successful but would NOT be successful at all if I tried to have a brick and mortar store in the area we live in). Over the difficult course of 12 years our family looks nothing like what my husband and I originally aspired to and what my husband and I still aspire to. My son hates being outside, he’s obsessed with technology. My children (both “double digits”) do not seem to value what we value and what we have tried and STILL try to instill in them. I love this newsletter but honestly, I feel so discouraged hearing how somehow families have managed to continue to live out their non-tech values without (seemingly?) a constant battle. I don’t know. Being “unplugged,” working in our large garden, listening to beautiful music, reading poetry, good literature, and surrounding ourselves with and pursuing the Good, True, and Beautiful in the myriad way that entails is still our goal…but oh my goodness it’s a battle. Do other people battle for this with their kids? My bubble has been popped in thinking this osmosis will just “happen” because we live this way, our children will live this way too! And I’m grieved in realizing that as hard as we have tried for some reason we just don’t seem to have the seamless time that this author has with creating a beautiful family culture that our kids are rooted next to us in. Anyway, I’m hanging on, praying and trying like crazy, but I would really love to hear a perspective from someone who struggles mightily for this vision, and largely alone since we don’t have extended family to draw on, and community in general is very sparse (and no, we can’t move somewhere else or change the culture here. We’ve tried). Thank you for any insights.

We've started using our digital camera again, and it's so much easier to download pictures into our computer. Literally take the memory chip out, and drag the file over. Done! Way more "convenient" than those apps, and more fun when snapping surprise pics of my wife in the garden:

https://romanshapoval.substack.com/p/ancestors